Eight years after the Fukushima nuclear crisis was triggered by a deadly tsunami, a fresh obstacle threatens to undermine the massive cleanup. Authorities say one million tons of contaminated water must be stored, possibly for years, at the power plant.

Last year, the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) said a system meant to purify contaminated water had failed to remove dangerous radioactive contaminants.

That means most of that water stored in 1,000 tanks around the plant will need to be reprocessed before it is released into the ocean, the most likely scenario for disposal.

Reprocessing could take nearly two years and divert personnel and energy from dismantling the tsunami-wrecked reactors, a project that will take up to 40 years.

Workers at the construction site of storage tanks for radioactive water at Tokyo Electric Power Co's (TEPCO) tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, February 18, 2019. /Reuters Photo

Workers at the construction site of storage tanks for radioactive water at Tokyo Electric Power Co's (TEPCO) tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, February 18, 2019. /Reuters Photo

It is unclear how much that would delay decommissioning. But any delay could be pricey; the government estimated in 2016 that the total cost of plant dismantling, decontamination of affected areas, and compensation, would amount to 21.5 trillion yen (193.4 billion US dollars), roughly 20 percent of the country's annual budget.

TEPCO is already running out of space to store treated water. And should another big quake strike, experts say tanks could crack, unleashing tainted liquid and washing highly radioactive debris into the ocean.

A 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck on March 11, 2011, off the Japanese coast, triggering a tsunami that killed some 18,000 people and the world's worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986. Meltdowns at three of the Fukushima Daiichi (first) plant's six reactors spewed radiation into the air, soil and ocean, forcing over 100,000 residents to flee. Many have still not returned.

International study

In addition to the reprocessing of polluted water, a study is being conducted by British and Japanese scientists to try to understand the exact sequence of events.

The Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) is currently collaborating with British researchers to learn more about the state of the radioactive particles created by the meltdown.

Dr Yukihiko Satou from the JAEA oversaw the transportation to Britain of particles collected from within the restricted zone, very close to the disaster site.

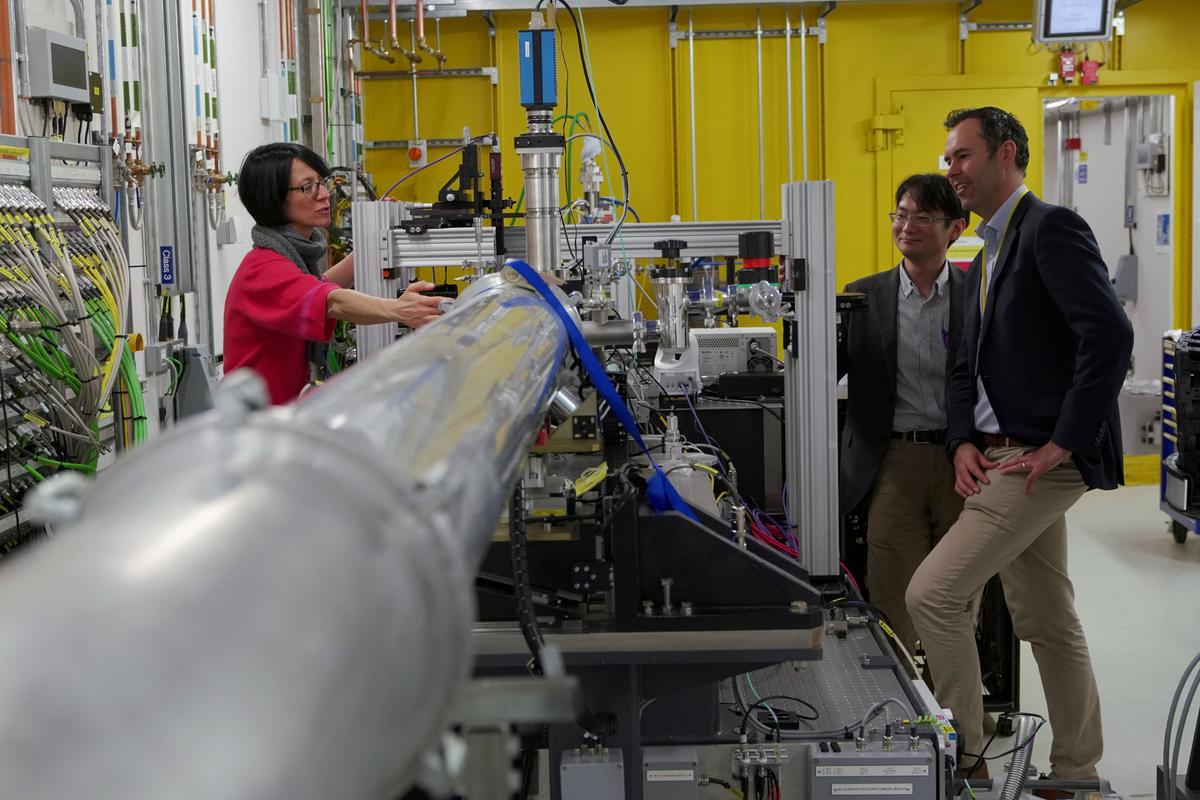

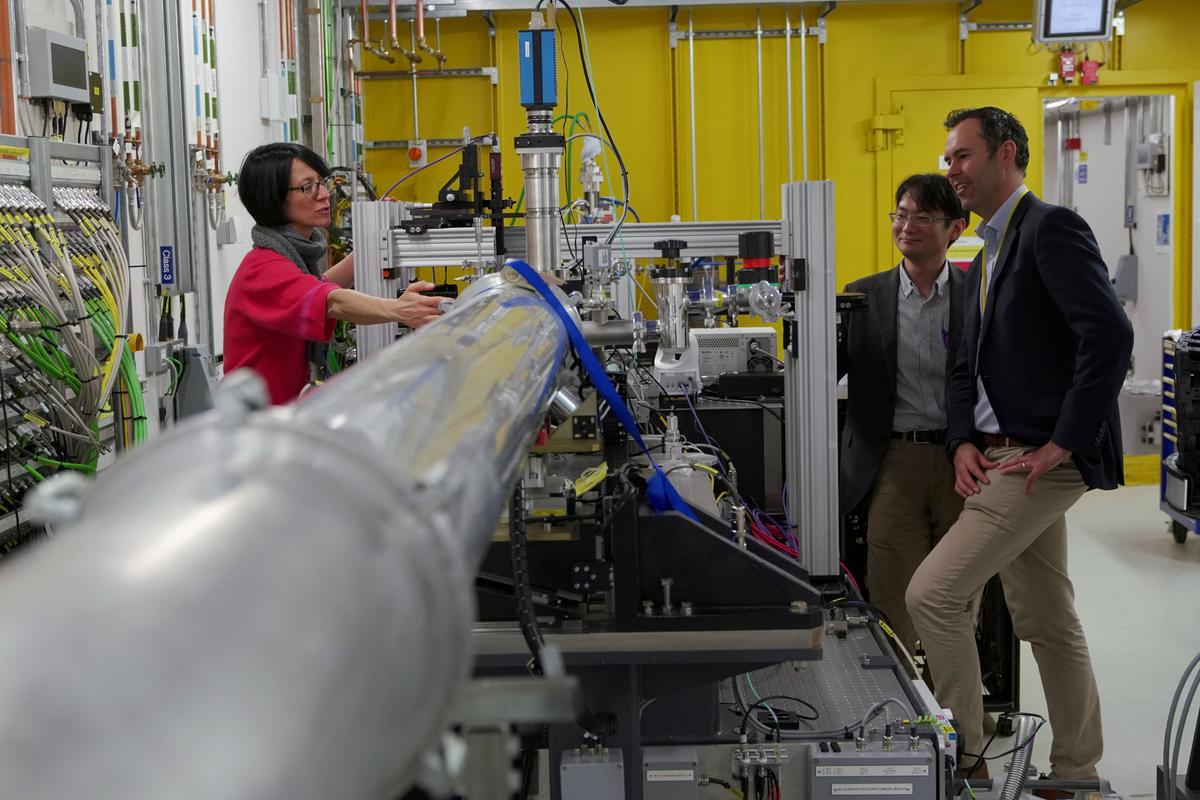

Tom Scott from the University of Bristol, Dr Yukihiko Satou from the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) and Silvia Cipiccia, beamline scientist, are seen at Diamond Light Source, Britain's national synchrotron, or cyclic particle accelerator, in Didcot, near Oxford, UK, November 16, 2018. /Reuters Photo

Tom Scott from the University of Bristol, Dr Yukihiko Satou from the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) and Silvia Cipiccia, beamline scientist, are seen at Diamond Light Source, Britain's national synchrotron, or cyclic particle accelerator, in Didcot, near Oxford, UK, November 16, 2018. /Reuters Photo

"The particles were fundamentally extracted from those attached to soil, dust and debris," Satou told Reuters.

Encased in protective tape, the samples were brought to the Diamond Light Source, Britain's national synchrotron, or cyclic particle accelerator, near Oxford.

Here electrons are accelerated to near light speeds until they emit light 10 billion times brighter than the sun, then directed into laboratories in "beamlines" which allow scientists to study minute specimens in extreme detail.

Researchers have created a 3D map of a radioactive sample using the synchrotron, allowing them to see the distribution of elements within the sample.

Understanding the current state of these particles and how they behave in the environment could ultimately determine if and when the area could be declared safe for people to return.

Fukushima evacuees not returning

With Japan keen to flaunt Tokyo 2020 as the "Reconstruction Olympics," people who fled the Fukushima nuclear disaster are being urged to return home but not everyone is eager to go.

Japan ordered more than 140,000 people to evacuate when the Fukushima Daiichi reactors went into meltdown, but many others living outside the evacuation zones also opted to leave.

A poll conducted in February by the Asahi Shimbun daily and Fukushima local broadcaster KFB found that 60 percent of Fukushima region residents still felt anxious about radiation.

Kazuko Nihei, who fled her home in Fukushima city with her two daughters after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, at her apartment in Tokyo. /AFP Photo

Kazuko Nihei, who fled her home in Fukushima city with her two daughters after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, at her apartment in Tokyo. /AFP Photo

Kazuko Nihei, who fled her home in Fukushima city with her two daughters in 2011, insists she won't return, even though government subsidies she once received have now ended.

She worries about "various health risks for children, not only thyroid (cancer) but others including damage to their genes."

"If there was a comprehensive annual health check, I might consider it, but what they are offering now is not enough, it only concentrates on thyroid cancer," she told AFP.

China's reaction: Import restrictions continue

Not long after the Fukushima disaster, the Chinese government tightened the restrictions on importing food and animal feed from Japan. Imports from some areas are banned while others are required to provide proof of non-radioactivity.

The customs administration has granted an exception: Rice produced in Niigata Prefecture was given import permission in November last year because it matched the safety standards in China.

(Top picture: Reactor units are seen over storage tanks for radioactive water at the Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s (TEPCO) tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, February 18, 2019. /Reuters Photo)