Opinion

12:24, 20-Apr-2019

Trend of mandarin learning and relocating of Chinese culture

Meng Ke

Editor's note: Meng Ke is a PhD candidate in the department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. The article reflects the author's opinion and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Language Days at the United Nations aim to celebrate global multilingualism and cultural diversity to promote equal use of the UN's six official languages. Backed by this agenda, April 20 has been selected as Chinese Language Day.

April 20 is the day of guyu (Rain of Millet), the 6th of the 24 solar terms in traditional East Asian calendars. This is a tribute to Cangjie, the legendary figure in Chinese myth who has created hanzi (Chinese Character). Word has it that when Cangjie invented Chinese characters, the deities and ghosts cried and the sky rained millet. In the Georgian calendar, guyu usually begins around April 20.

"In the global market, learning Chinese is essential, vital… as China's economy has experienced an astronomical boom over the past decade," says Jess Young, a writer for The London Economic.

"China has the largest manufacturing sector in the world with a record number of exports every year, and with this country becoming the fastest growing consumer market, learning the native language proves to be an excellent investment, especially for UK companies."

This phenomenon may act as the primary drive for foreigners to learn mandarin.

Florence Liu, a mandarin tutor in Practical Mandarin and one of the most influential Chinese-teaching specialists in London, illustrates this trend by sharing her own experiences of teaching mandarin. Her students are adults who come to learn mandarin for a variety of reasons, and most of them are business owners, expatriates and job seekers.

Business owners learn mandarin to expand their businesses in China, to find potential partners and to recruit Chinese employees at a relatively low cost. Expatriates usually are required (and paid) to learn mandarin by their employers.

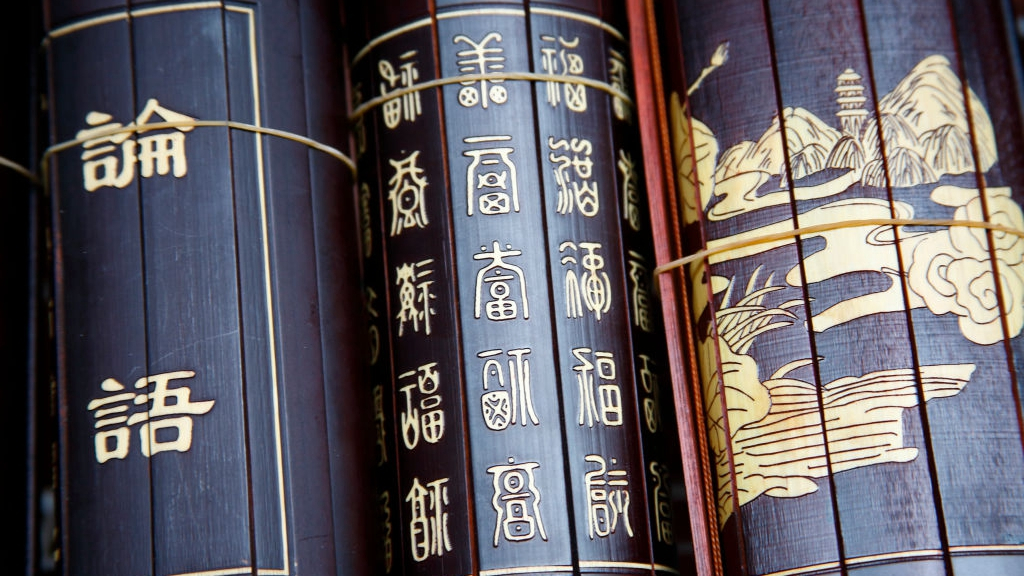

Chinese characters conveying traditional virtues /VCG Photo

Chinese characters conveying traditional virtues /VCG Photo

Living and working in China for a long time, these expats need to engage with the local Chinese community intimately, at least on the level of speaking the language. Job seekers, little doubt, have to learn mandarin if they chase after well-paid occupations in today's, where a westerner's face no longer automatically and easily earns a good salary.

The learning of language always accompanies the acquiring of its culture. In our contemporary times, how do we define Chinese culture, and how can we perform it in the eye of foreigners? For different organizations or individuals, the answer varies.

For institutes sponsored by the Chinese government, such as many Confucius institutes affiliated to universities, "Chinese culture" is usually a synonym to the performative embodiment of traditional culture. Therefore, tasting sessions like Chinese calligraphy, tai chi martial art and Chinese knotting are usually offered together with their language courses.

Little doubt, these tasting sessions are just add-ons for those businesspersons. They have clear objectives of learning mandarin: to make as much profit as they can in China by better knowing and understanding local people.

Nevertheless, traditional culture does entice passionate learners who do not see Chinese culture from a perspective of orientalism, but instead devote themselves wholeheartedly to the study of traditional Chinese literature. As a graduate teaching classical Chinese literature at university, I would like to share my experience.

Unlike businesspersons who have practical objectives, my students are undergraduates who clearly showed great passion for Chinese literature, either modern or premodern. The course I taught was translation and classical Chinese literature, and I was in charge of drama literature.

Participants write Chinese characters on whiteboards at the final of a Chinese language dictation contest at the Vladivostok branch of Confucious Institute at the Far Eastern Federal University, Russia, February 8, 2017. /VCG Photo

Participants write Chinese characters on whiteboards at the final of a Chinese language dictation contest at the Vladivostok branch of Confucious Institute at the Far Eastern Federal University, Russia, February 8, 2017. /VCG Photo

I selected several scenes from Peony Pavilion as my teaching material. Through word-to-word translation and free discussion on Chinese poetics and lyricism, most of my students were elicited by not only this legendary love story, but also its underlying socio-cultural structure.

Their translations might not be the most "accurate" (even accuracy per se doesn't matter anymore), but full of curious perspectives and brand new interpretations. They asked questions which we natives would never ponder upon. Thus, to some extent, working with these passionate learners will also enable the native to examine her own culture.

While traditional culture plays a significant role in China, we shall never forget that the definition of culture, the performing and the imagination of it should be without any constraint. In Liu's classes, rather than merely use textbooks, Liu extensively shows video clips from mandarin-centered media such as Pearvideo, Kuaishou, Douyin and Miaopai to exhibit the lives of ordinary Chinese people.

Actually, her initial intention is to provide a more realistic context of contemporary China, as the textbook is appallingly out of date. Not a single person in reality talks like those in the textbook.

Therefore, Liu uses these video clips to teach her students some glossaries and slang in China that people actually use. By doing so, her students can at least partially approach the real lives of Chinese people.

What do they care about? What do their lives look like? What kinds of topics they are talking about? How do they socialize in public space? How do they establish their own online and offline communities? Why do they enjoy making and watching those video clips? The answers to these questions are exactly challenging our definition of culture.

The Chinese community of Rome during New Year celebrations in Rome, Italy, February 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

The Chinese community of Rome during New Year celebrations in Rome, Italy, February 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

Culture should not be something fixed, materialized, displayed in museums and performed to feed exoticism. Culture is about humans. It's all about living human beings. It's their daily lives, the people they love and resent, the food they eat, the clothes they wear and the leisure they enjoy that defines who they are.

It's the foreigner's intersubjective engagement with local people rather than distant and indifferent observation.

Maybe it is still too bold to conclude that learning mandarin is trendy, but there definitely exists a rising trend. As an economic entity, many corporations yearn to do business with, China itself has already stepped on to the center stage of our globalized world.

If China – by China I mean any authority, organization, institute or individual who recognizes "Chineseness" and has a sense of belonging – desires to promote Chinese culture, or more precisely, to secure Chinese culture more visibility on the world stage, language is mandatory but not sufficient. Perhaps it is high time to rethink, re-imagine, and re-map what is culture.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3