Politics

16:49, 17-Jan-2019

Split fears make cross-party Brexit deal a tough task

Updated

20:13, 17-Jan-2019

By John Goodrich

Party discipline has largely broken down in the British parliament, with one exception: self-preservation.

On Wednesday evening Conservative MPs voted together to keep the government in office, as Labour representatives attempted to force an election.

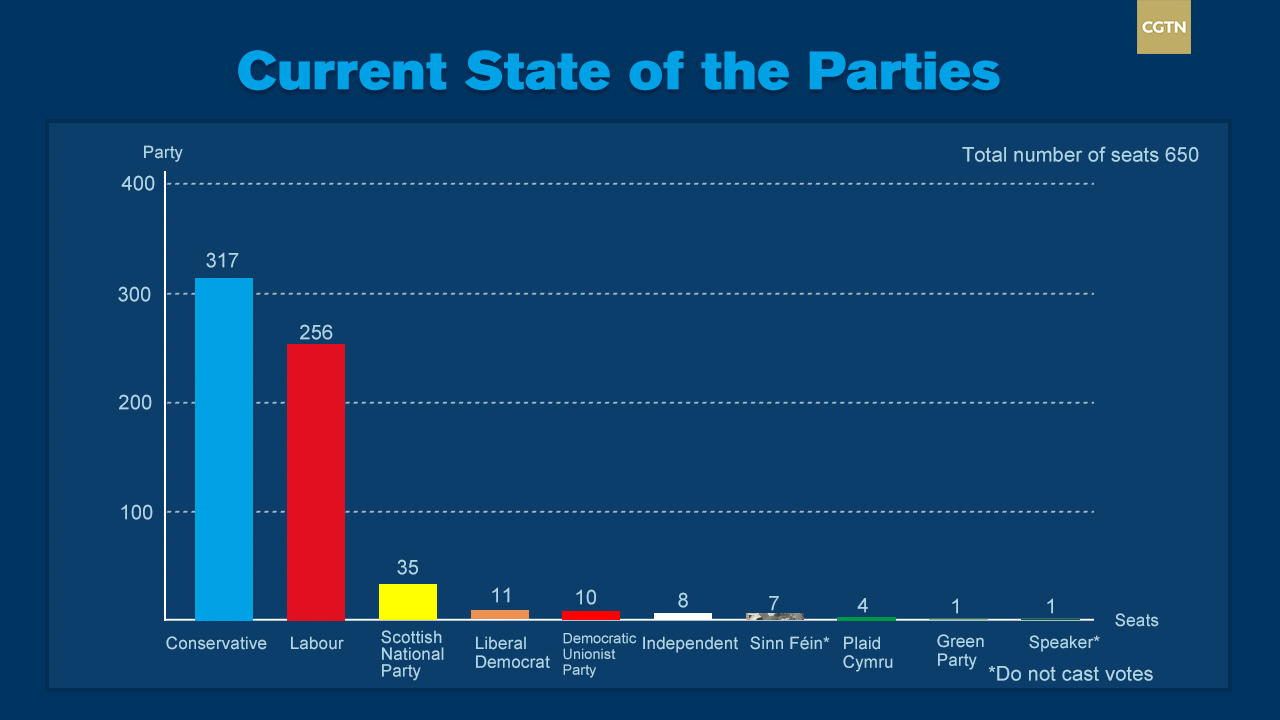

Prime Minister Theresa May survived the vote 325-306, but without 10 votes from the Democratic Unionists (DUP) she would have lost the confidence of parliament.

Just 24 hours earlier, the picture was very different.

The DUP joined with 118 Conservatives to crush May's plan for Brexit, and a long-running split in the Labour Party broke into public view with over 70 of its MPs signing a letter in support of a second referendum.

The inflexibility of these factions makes striking a compromise deal that attracts a majority in parliament both difficult and risky.

Difficult, because there are multiple groupings with conflicting aims and tribal instincts.

Risky, because the future of the two main parties is at stake.

While the Liberal Democrats and UKIP are united in respective pro- or anti-EU positions, the Conservatives and Labour are big tents – their MPs hold wildly different views, particularly on Brexit.

Britain's Prime Minister Theresa May makes a statement following winning a confidence vote, after Parliament rejected her Brexit deal, outside 10 Downing Street in London, Britain, January 16, 2019. /VCG Photo

Britain's Prime Minister Theresa May makes a statement following winning a confidence vote, after Parliament rejected her Brexit deal, outside 10 Downing Street in London, Britain, January 16, 2019. /VCG Photo

After Tuesday's crushing defeat, May sought to reach across the House of Commons for support from opposition parties. To find common ground she will have to move closer to Labour's Brexit proposal: a customs union, a closer relationship with the single market, and protections for workers.

If the prime minister were to offer such a deal, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn would likely be interested. He is eager to avoid a second referendum – creating a split with his own MPs and members in the process – and wants to move on from Brexit.

Such a compromise would have a chance of gaining a majority, uniting many Labour MPs with moderate Conservatives. And crucially, given that May needs them to support her government in the future, it may receive backing from the DUP.

01:58

French President Emmanuel Macron suggested on Tuesday that the EU “already went as far as we could,” but the bloc's chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, said the EU would "respond favorably" to a change in the UK approach to a customs union, which allows for no internal tariffs and common external tariffs.

However that shift would prevent the UK from pursuing an independent trade policy, and so would be fiercely opposed by a large chunk of the Conservatives.

This faction opposes the "Irish backstop" because it threatens to keep the UK in a temporary customs arrangement post-Brexit – a permanent customs union is exactly what this group does not want.

00:56

Lexington Communications' Paul McGrade told CGTN, "She's (May) now got to go on and try to put together some sort of cross-party consensus in a very divided Westminster parliament on some kind of Brexit deal that can command a majority of MPs."

"That's going to be an incredibly difficult balancing exercise and it's going to be very hard to see how she gets that majority without splitting her own party."

The prime minister could alternatively shift towards the hardline faction in her party, many of whom would back her deal if the backstop was removed. "Only one single thing needs to change,” Conservative MP Ben Bradley told the Guardian. “An alternative to, or exit mechanism from, the backstop would in my view get a majority in the Commons."

Yet this would require the reopening of the Withdrawal Agreement – which the EU refuses to do. Brussels is wary of the consequences of a hard border between northern and southern Ireland, and will support the interests of its member – the Republic of Ireland – rather than Britain.

For Labour, there are also risks of division: between moderates and Corbyn-backers, between membership and leadership on a second referendum. The risk of factions from both parties breaking away has grown, with growing speculation of a serious new centrist party emerging.

But May, who has now opened talks with opposing MPs, now faces unenviable choices: Strike a deal that can pass parliament and risk splitting her party for good, harden her approach and alienate other parties and the EU, cling to a deal that was crushed by MPs, or back a second referendum or no deal.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3