Culture

13:00, 13-Apr-2019

China debates the moral of the Little Mermaid story

By Zhou Minxi

Once upon a time, little girls wanted to be princesses from fairy tales. While many grow up to stop believing the stories of happily ever after, some question the morals of them by modern standards.

Recently, a Chinese mother's social media post about how "The Little Mermaid," the original story written in 1836 by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, could be a bad influence for her young daughter sparked a heated public discussion about the morals of fairy tales.

In a Weibo post, the mother argued that it makes no sense that the little mermaid risks all – her own voice, her family's resources (sisters' hair), the excruciating pain of walking on legs and ultimately, her life, only to lose everything for a man she barely knows.

She explained to her daughter that as a human girl, she is smarter than the fish and should know that "no one is worth giving your life for." Believing the story sends a wrong message to girls, the mother said she had to turn off the audio book before the tragic tale could reach its conclusion.

The Chinese woman added that all princess stories with a "happy ending" are misleading, too, because "girls don't have to be harmless and docile, and marrying a prince isn't the only outcome," she wrote.

As Chinese women become increasingly awoken to their desire for equality, the once popular "fairytale romance" in fictions and on screens, particularly those of the Cinderella-esque variety, is now considered by many as cliched and retrograde.

A scene from Disney's 1989 animated movie "The Little Mermaid." /AP Photo via Disney

A scene from Disney's 1989 animated movie "The Little Mermaid." /AP Photo via Disney

Fairy tales are open to interpretation

The Chinese mother's views on fairy tales echoed what many Western scholars, writers and parents have been saying for decades. It has been pointed out abundantly that many fairy tales promote archaic ideals of femininity and gender roles. And in contrast with the heroine's beauty and innocence, the "evil witch" trope that portrays powerful women as old, ugly and scheming is believed to have roots in medieval misogyny.

Speaking on a talk show last year, actress Keira Knightley said her three-year-old daughter was not allowed to watch Disney's 1950 adaptation of "Cinderella."

"Because she waits around for a rich guy to rescue her," Knightley said. "Don't. Rescue yourself, obviously."

The star also criticized the Little Mermaid for giving up her voice for a man, a reference to women not having their opinions.

Another celebrity mom, Kristen Bell, who provided the voice for Princess Anna in Disney's "Frozen," called out Snow White over sexual consent and said she regularly questions the 1937 film's suitability for her daughters.

But stories are not set in stone. Contemporary authors including Angela Carter and Catherine Breillat have reworked Charles Perrault's classics from a feminist perspective.

Disney's more recent adaptations, such as "Beauty and the Beast," "Frozen" and "Maleficent," have brought forth independent princesses and relatable villains, reflecting a shift in female representations.

The Little Mermaid statue sits on a rock in the harbor in Copenhagen, Denmark. /AP Photo

The Little Mermaid statue sits on a rock in the harbor in Copenhagen, Denmark. /AP Photo

It is no secret that Disney has sanitized fairytales to make its movies more family-friendly. Those unfamiliar with the original stories may not be aware of the unpleasant parts which were taken out of Disney's sunny versions.

Harvard professor Maria Tartar, an expert on folklore, explored in depth in her book that many of the original tales were rather violent and not meant for children to begin.

Like Disney's feel-good musicals, the earlier stories by Perrault and the Grimms Brothers too were revised with added moral lessons, as Tartar and others pointed out, to serve as cautions for children at the time.

Some educators have argued that if anything, fairytales can be a good place for parents to start a conversation about difficult subjects with their children. And banning the stories from the home does not prevent a child from encountering similar dilemmas later in life.

"The little mermaid never attained her objective and died because of her choices, making the story more of a warning than a tale," Kidd Dark wrote in a literary critique for Medium.

The moral of the story according to author and translator

An enduring cultural symbol of Denmark, Andersen's mermaid was introduced to children in China thanks to a writer named Ye Junjian, who was the first Chinese to translate Andersen's fairytales from Danish.

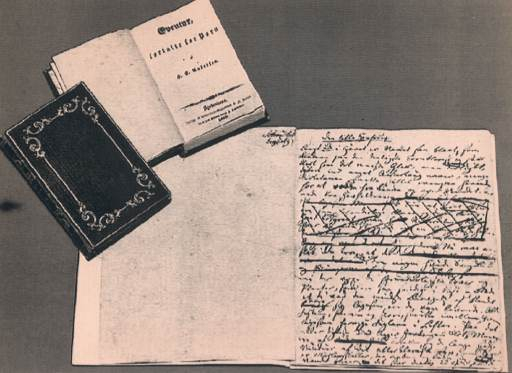

The original handwritten copy of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid" seen in a museum in Denmark. /AP Photo

The original handwritten copy of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid" seen in a museum in Denmark. /AP Photo

The translator was said to have loved the little mermaid story in particular. While he was reading literature at Cambridge University in 1940s, Ye was deeply moved by the mermaid's noble spirit. Then he learned Danish and made it his life's mission to bring Andersen's fairytales to Chinese readers.

Ye's translation, published in China in 1958 and 1978, was recognized in Denmark as the best among over 80 languages.

Ye later wrote that "The Little Mermaid" was a celebration of humanity, which is embodied by the human prince in the eyes of the mermaid. It is her quest for a human soul rather than a man's love that sets the protagonist on her journey.

And it is her selflessness, a human quality transcending the love between a man and a woman that makes her worthy of an immortal soul.

However, Disney's 1989 movie "The Little Mermaid" has given Ariel the title character a generic happy ending, a far cry from Andersen's original tale about sacrifice and redemption.

Andersen wrote in 1837: "I have not…allowed the mermaid's acquiring of an immortal soul to depend upon an alien creature, upon the love of a human being... I have permitted my mermaid to follow a more natural, more divine path."

The idea that the heroine is able to earn her own immortality rather than depend on marriage, critics say, actually makes the seemingly bleak tale more far-sighted than Disney's happy one.

"Only humans can change their destiny," Ye wrote on Andersen's message. "There is always hope."

And that might not be too bad a message for kids.

(A Chinese performer plays a mermaid in an aquarium in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, December 16, 2016. /Reuters Photo)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3