Opinions

21:39, 24-Oct-2018

Opinion: What to make of the warming of Sino-Japan relations?

Updated

20:41, 27-Oct-2018

CGTN's Xu Sicong

Editor's note: This article is based on an interview with Yang Bojiang, Deputy Director of the Institute of Japanese Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The article reflects the expert's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

China-Japan relations suffered a major setback following the intensified territorial dispute over the Diaoyu Island in 2012. Now after years of strained relations since then, the two sides have finally come to mend fences.

The first sign of the change came about in May 2017 when the Japanese government, which had previously kept the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) at arm's length, sent delegates to attend the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing. The following month, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe indicated a willingness to participate in the BRI.

Since then, the two sides have seen a series of exchanges of high-level official visits taking place aimed at improving bilateral ties and deepening cooperation in areas such as infrastructure development. These exchanges finally led to Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's four-day official visit to Japan this May, the first such visit by a Chinese Premier in eight years.

In another big development, Shinzo Abe is going to visit China from October 25 to 27, the first official visit to China by a Japanese prime minister since 2011.

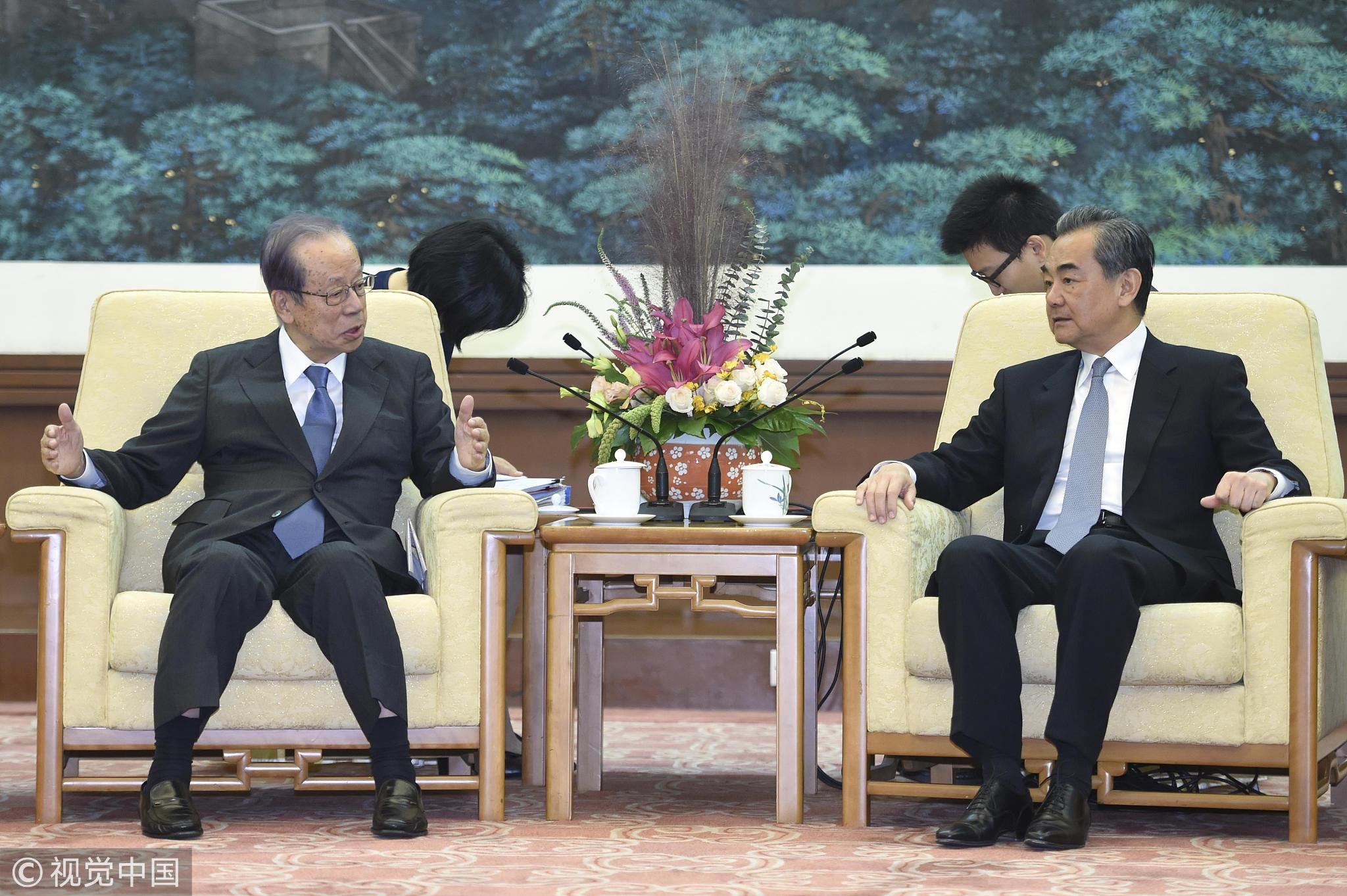

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) and former Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda talk at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October. 10, 2018. /VCG Photo

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) and former Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda talk at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October. 10, 2018. /VCG Photo

How did relations warm?

US President Donald Trump is believed to have partly played a role in the warming of relations. So far the Trump administration has imposed tariffs on the Chinese imports worth 250 billion US dollars.

And Japan, the second biggest "contributor" to the US trade deficits, with the country's trade surplus with the US standing at 68.8 billion US dollars in 2017, is easily the next potential target for Trump. Both China and Japan have been advocating multilateralism and the free trade system more than ever in the face of the mounting threats of trade wars from the US. Thus, in a way, Trump has pushed China and Japan into each other's arms.

Another factor that has contributed to the improved bilateral relations relates to the changing situation on the Korean Peninsula starting from the beginning of this year.

The thaw in relations between the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), the US and the Republic of Korea (ROK) have serious ramifications for the regional security situation, which Japan weighs its policies heavily against.

The country worries about the fact that it has been sidelined during the negotiations between these three parties and the country needs China's cooperation on a series of issues concerning Japan-DPRK relations, such as the abduction problem as the DPRK government abducted many Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s.

While the needs of the two countries to cooperate have always been present, it is the external environment that made them seem more pressing than ever.

Chinese tourists learn how to make Japanese Sushi in Kyoto, Japan on March 21, 2018. /VCG Photo

Chinese tourists learn how to make Japanese Sushi in Kyoto, Japan on March 21, 2018. /VCG Photo

Is there a structural change in the bilateral relations?

However, caveats should also be added to the recent rapprochement, as there remains fundamental disagreement over a number of issues, with the security issue being the most prominent one.

One of Shinzo Abe's central policy goals is to change Article 9 of the Constitution. If Abe was successful in his bid, it would then allow Japan to legally have a military, possibly breaking away from the post-war arrangement that prohibits the country from waging war and obtaining “war potential”, which would largely unsettle its neighbors including China and South Korea.

Besides, even though Japan seems to have had a change of heart on the BRI, it has not fully embraced it yet. For example, while showing interest in cooperating with China on the BRI in “third countries”, Abe has also set out a number of conditions for Japan to take part in the BRI projects.

And given the two countries' history, the long-standing territorial disputes and the uncertainties in the Indo-Pacific region, tensions are likely to be reignited in the future if trust is not in place and disagreement not properly handled.

Nevertheless, potential risks should not deter the two regional economic powerhouses from deepening cooperation, as the two countries share enormous common interests in deepening economic ties and cooperating on issues such as non-traditional security.

Premier Li's visit to Japan earlier this year witnessed the signing of numerous cooperation agreements covering areas including investment, social security and cultural exchanges. The two sides also announced a communications mechanism to avoid maritime and air collisions.

Therefore, even though it would be hard to see a total reversal of the underlying structural dynamics between China and Japan, more pragmatic approach to the bilateral relations that could serve to maximize the two sides' interest under the current framework should be adopted.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3