In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, landing in the Americas while trying to reach India. He brought back the news of an exploitable land of riches and resources to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile, the rulers of Spain. Columbus set off a frenzy of imperial conquest among Old World Europeans.

Over five centuries after Columbus proved through navigation pluck that the world is round, three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Thomas Friedman roiled the world with his bestseller "The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century" after a journey to India's hi-tech city of Bangalore. In it, he recounted how a fusion of state-of-the-art technologies is changing our lives at an unimaginable speed while leveling the economic playing field.

These two events bookend what can be defined as different eras of globalization, from one of exploitation to one of increasing cooperation and interdependence. But is this trend inevitable, or will we experience tectonic shifts resulting from unforeseen issues in the process of integrating people from different backgrounds and circumstances?

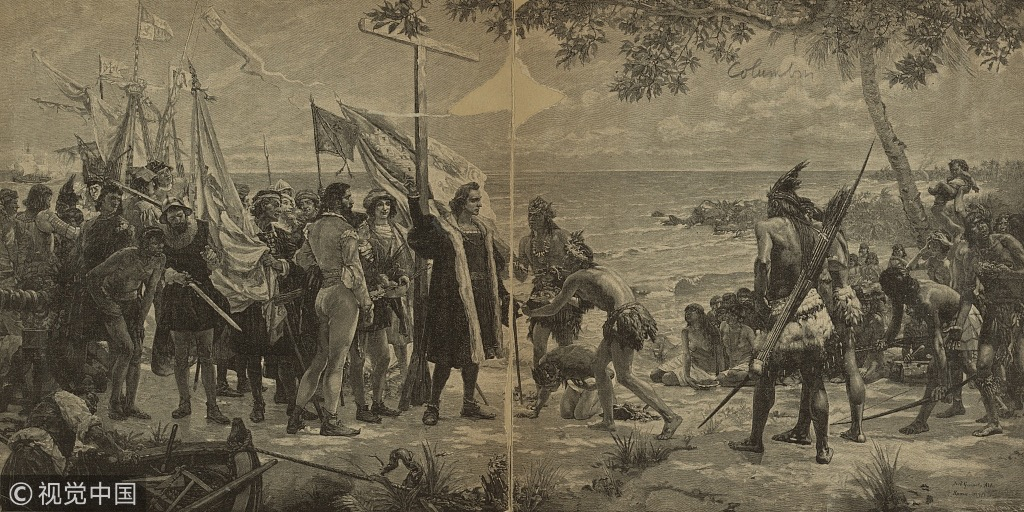

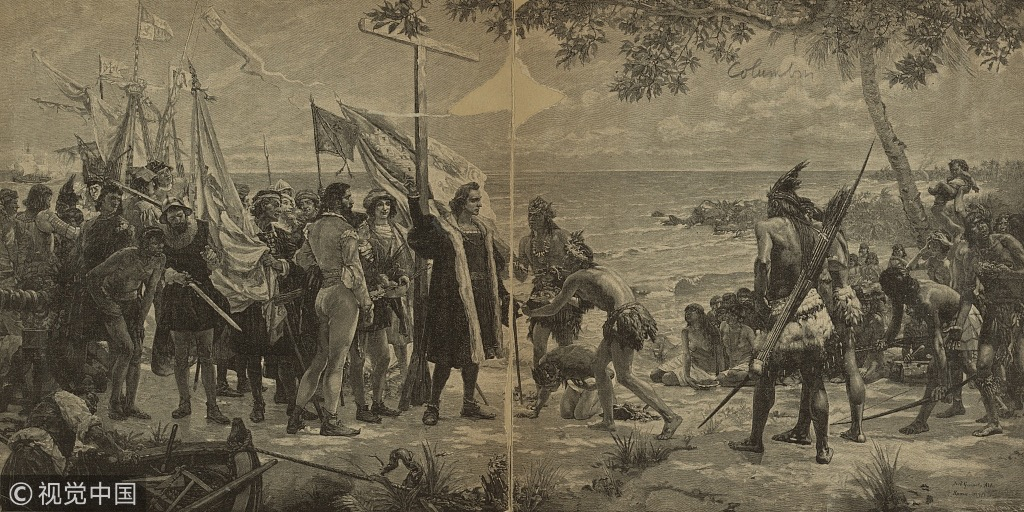

Illustration depicting Christopher Columbus meeting indigenous peoples of the Americas, 1890. /VCG Photo

Illustration depicting Christopher Columbus meeting indigenous peoples of the Americas, 1890. /VCG Photo

Globalization 1.0 – Rise of sea powers

Years after Columbus' landmark discovery, Vasco da Gama set sail with an expedition to reach the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa and then to India, establishing a sea route connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the mysterious Indian kingdoms. The two voyagers opened the floodgates to a new epoch: globalization, a term, however, that made its debut centuries later in 1962.

The first episode of globalization reunited people separated for over 10,000 years. It was during this age that coffee told a tale of migration from Ethiopia to Europe, humble potatoes traveled from the Peruvian soils to dinner plates around the world, and chili peppers found a spice route from South America to East Asia. The flow of food on maritime routes was the dawn of global trade.

It was an age made possible by sea powers, bringing contact between different civilizations with unprecedented efficiency. From the late 1400s to the early 1800s, the world shrank from large to medium with countries globalizing. This trend, however, did not result in respect for indigenous cultures, but rather brought about their exploitation through imperialism.

Locomotive No. 148 at London & South Western Railway. /VCG Photo

Locomotive No. 148 at London & South Western Railway. /VCG Photo

Globalization 2.0 – Pax Britannica

The second period of globalization came in the midst of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. Spanning from the 1760s to the 1840s, this revolution was a stage of painstaking transition – from handicraft workshops to factories with humming machines, and from an agrarian society to an urbanized one.

People started using fossil fuels to power machines that enabled production and movement. Plus, the wide utilization of iron and steel accelerated the pace toward heavy industrialization. The Spinning Jenny and the power loom greatly enhanced the making of textiles.

Bringing all of this together was the steam engine, which allowed for human productivity at a scale never seen before. Besides being a commercial success, steam carriages, locomotives and boats entirely altered the sea-powered trade pattern and buoyed land-powered economies.

This second episode saw the world further shrinking from medium to small as cross-border companies spearheaded integration and development. But while it precluded the prosperity of Britain and the European continent, which contributed 47 percent to the world economy back then, Asia, Africa and certain regions in the Americas ground to a halt due to colonization and plundering of their resources. In many a place, old civilizations were brought to their knees.

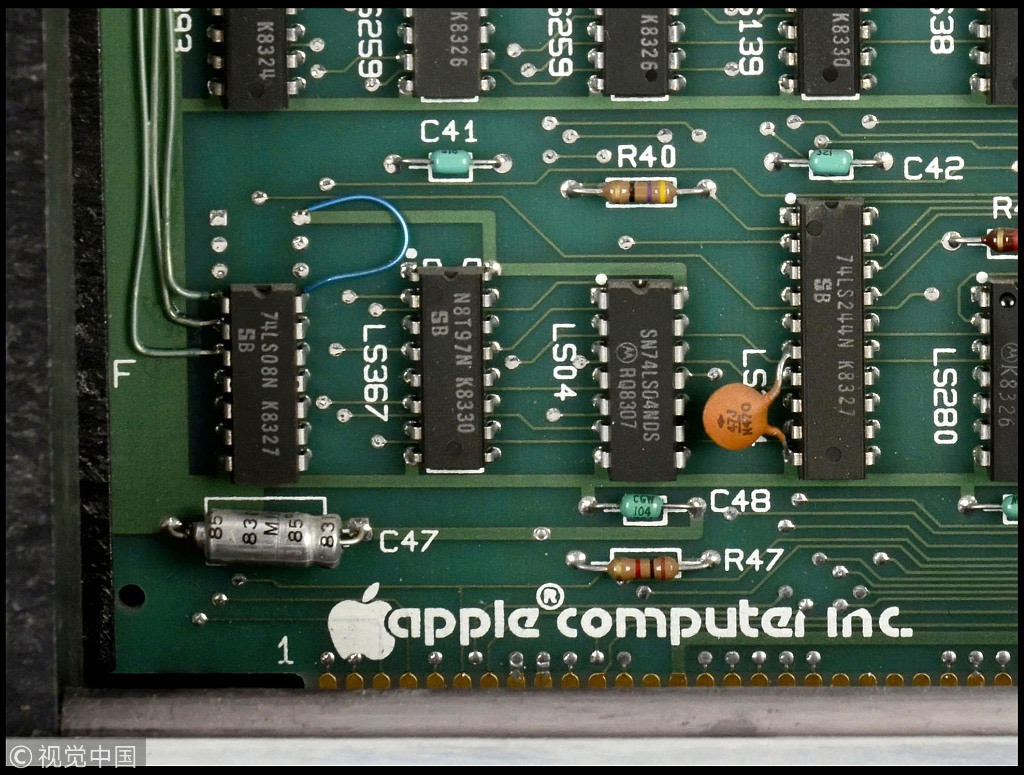

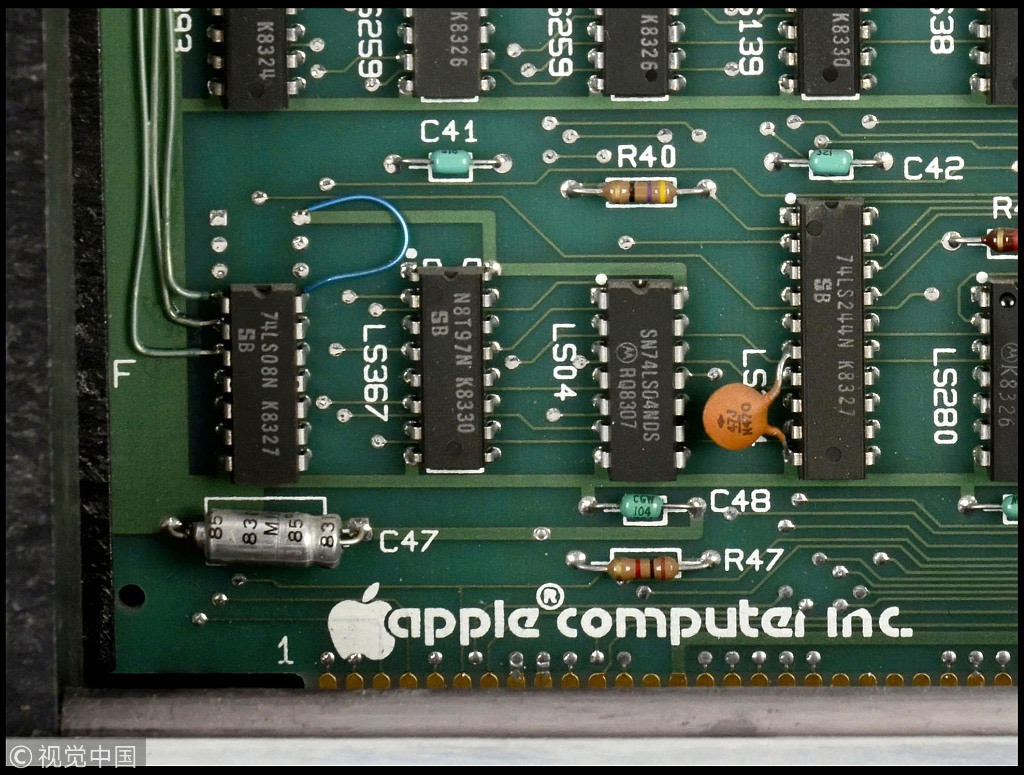

A rare surviving Apple computer that was the first to use a mouse has emerged for sale for £30,000. /VCG Photo

A rare surviving Apple computer that was the first to use a mouse has emerged for sale for £30,000. /VCG Photo

Globalization 3.0 – Pax Americana

As Adam Smith forecast in "The Wealth of Nations," however, Europe would "grow weaker." The two world wars tanked the European economy, and global dominance shifted to the United States in the 1950s, when its economy amounted to 27 percent of the world total.

As such, the U.S. pioneered the third era of globalization, bringing interconnectivity to the individual. Personal computers and a worldwide network freed people from their immediate physical environments, allowing them to learn, communicate and contribute wherever they were. No longer were resourceful workers constrained by poverty or lack of opportunity, because now they could compete with the brightest and the most advantaged in developed nations.

The flow of information characterized this third epoch, as knowledge became the primary currency for generating wealth and prestige, ultimately lowering the barriers to entry for work of higher economic value than manufacturing and basic services.

As with the previous eras, this one was not completely rosy. Successful entrepreneurs in tech and high finance became unimaginably wealthy in advanced nations such as the U.S., contributing to an inequality nearly as vast due to a stagnation in the real wages of blue-collar workers. Meanwhile, companies moved jobs overseas to countries such as China and India, due to lower labor costs and a vast pool of skilled workers.

The shortsightedness of such employers meant that those who lost work to more competitive markets found themselves growing resentful by the day, as they struggled to make a living for themselves and their families. This ill will transformed into hatred, which in turn spurred massive movements of nationalism that changed the political and social landscape of many democracies. So even as the world became "flatter," the neglected retreated into their own groups.

An Alpha Mini robot that use artificial intelligence dances at the Las Vegas Convention Center during CES 2019 in Las Vegas, January 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

An Alpha Mini robot that use artificial intelligence dances at the Las Vegas Convention Center during CES 2019 in Las Vegas, January 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

Globalization 4.0 – Whose globalization?

Building on the integration of the previous eras, the fourth period of globalization brings about automation and "smart" services that will pervade every aspect of our lives. From self-driving cars to the Internet of Things, we will see our physical world become increasingly digital and convenient.

As for which country will lead us into this new era, the key contenders are the rising China and the established U.S. Perhaps another nation will take the lead. Or maybe the construct of a nation will not matter much because smart interconnectivity would emphasize cooperation between regions, cities, and communities around the world.

However, material abundance decoupled from human labor may not be the panacea to all of our problems, as products and resources could be unevenly allocated, meaning that inequality would continue to exist with the few having the plenty.

Preparations are made ahead of the 49th World Economic Forum annual meeting themed “Globalization 4.0: Shaping a Global Architecture in the Age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution” in Davos, Switzerland, January 21, 2019. /VCG Photo

Preparations are made ahead of the 49th World Economic Forum annual meeting themed “Globalization 4.0: Shaping a Global Architecture in the Age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution” in Davos, Switzerland, January 21, 2019. /VCG Photo

Moreover, if we cannot apply "smart" tech to finding alternative paths to exploiting our diminishing natural resources of water, arable land and fossil fuels, then conflicts could intensify even in a globalized world.

Apart from that, this new chapter of globalization is igniting a tech war between powerhouses of chips and algorithms. We are seeing more chaos than ever in this stage – violation of established rules, fragmentation of commons, a resurgence of populism and regionalism. As world leaders gather in Davos to discuss both high and low politics, trying to create order from such chaos, these issues will undoubtedly be on their minds.

For those who question their place in our world order, is globalization a blessing, or a curse? More importantly, is it still the period of Pax Americana, or an era of China, or a century of the world?