Art

21:37, 17-Aug-2018

Tibetan artists strive for revival of Thangka

Updated

21:18, 20-Aug-2018

By Yang Jinghao, Zhang Youze

03:24

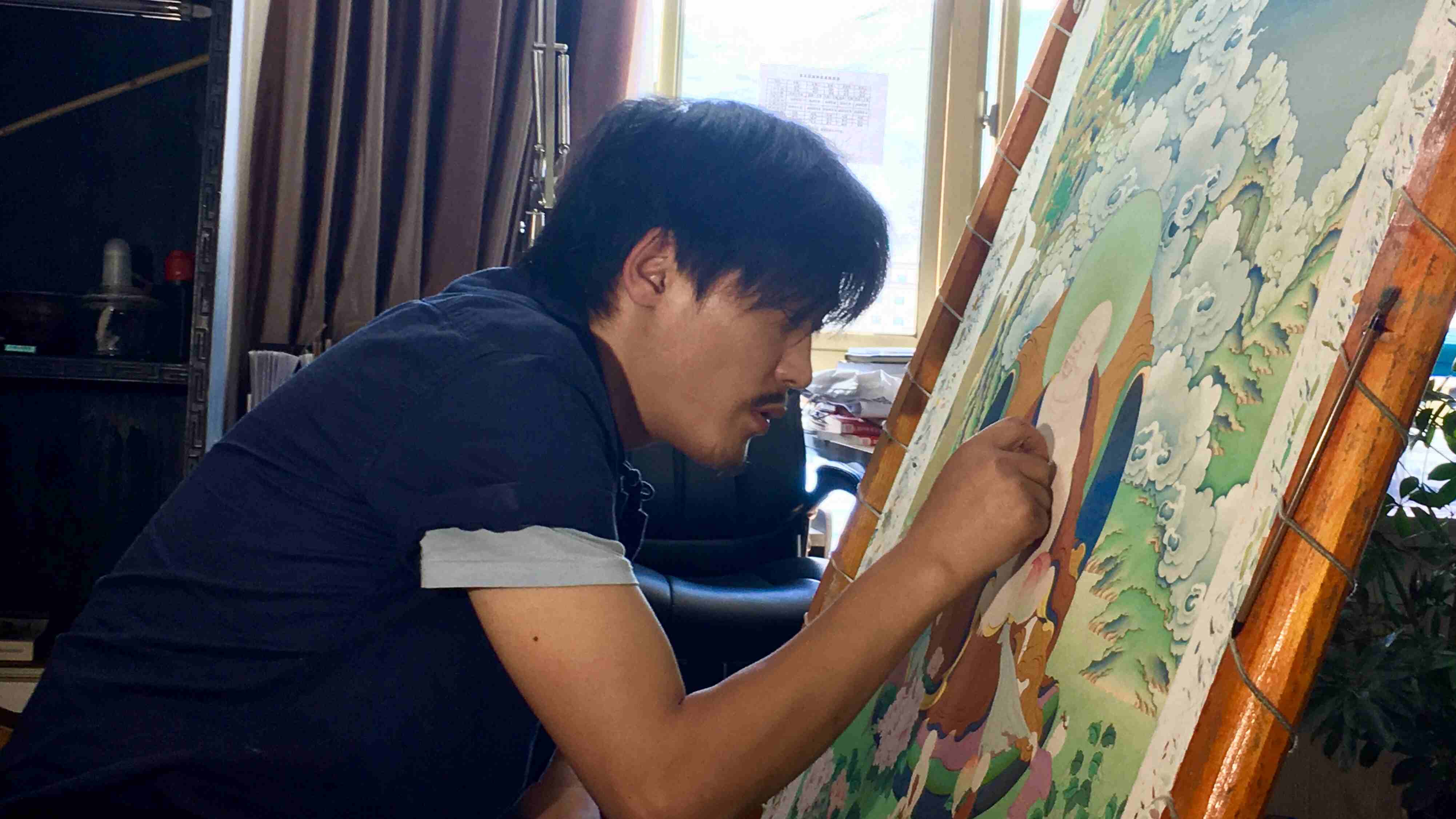

With his stylish look and fluent Chinese (Mandarin), one might be hard to associate Tenzin Phuntsok with an artist of Thangka, a form of religious artwork that typically depicts a Buddhist deity and can be traced back to the 10th century.

Tenzin Phuntsok's family, from Lhasa, capital of Tibet Autonomous Region, was devoted to the traditional culture for generations before he was born, and his passion for painting started in childhood.

“My father selected an auspicious day when I was 13 to hold a special ritual to accept me as his apprentice. That’s when I started learning Thangka painting,” Phuntsok told CGTN.

A monk from southwest China’s Sichuan Province learns Thangka painting at the school established by Tenpa Rabten. /CGTN Photo

A monk from southwest China’s Sichuan Province learns Thangka painting at the school established by Tenpa Rabten. /CGTN Photo

Different art forms and schools influenced Phuntsok's perception of painting during his college years. He thought that Thangka might not be his only choice.

“I was so attracted to some contemporary art, which my father said was contrary to our traditional art. So we frequently argued,” the 33-year-old said.

His father, Tenpa Rabten is a well-known Thangka master in Tibet. He is the first person to bring the Thangka painting into the higher education system.

Tenzin Phuntsok chose to be a Thangka painter and a college professor after graduation. He explained this as he “grew up and understand deeper about the traditional culture.”

Dedicating himself to the unique culture of the Tibetans became his responsibility in 2014. That’s when he took over the school his father established in the 1980s.

Tenzin Phuntsok teaches a student at his school the techniques of Thangka painting. /CGTN Photo

Tenzin Phuntsok teaches a student at his school the techniques of Thangka painting. /CGTN Photo

“There were only about 20 Thangka painters in Lhasa back then. My father felt it was urgent to save the culture, and so he broke the tradition that the craftsmanship could only be passed down to male descendants and trained whoever wanted to learn it,” he said.

Decades on, the school has cultivated hundreds of painters free of charge. Today, it is still attracting admirers from across the world, mostly Tibetan herdsmen from remote areas, who need to spend at least six years acquiring the demanding skills.

Dorji Tseten is one of the learners at the school. He is from Aba Qiang and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in southwest China’s Sichuan Province. He said he had never expected Thangka painting to be so difficult, which usually takes at least six years to master.

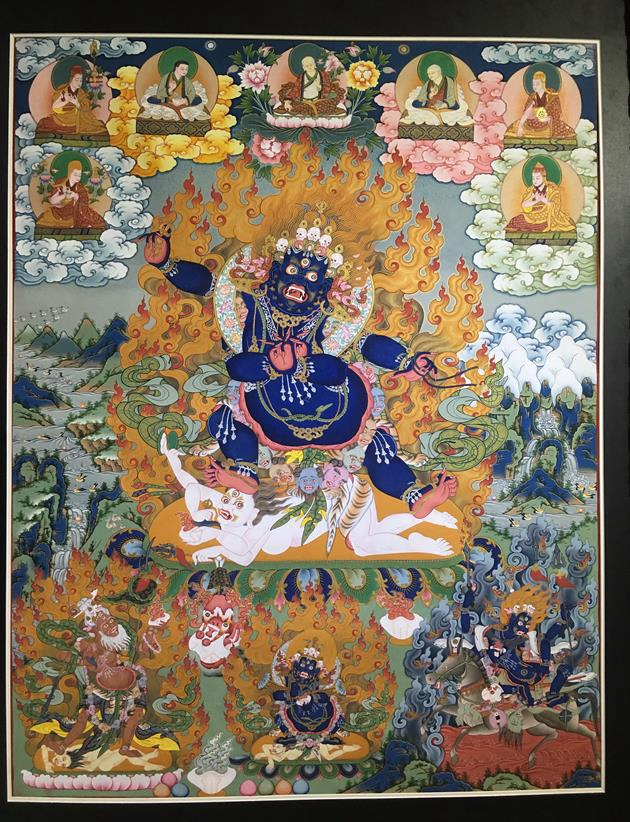

A Thangka painting exhibited during the week-long Shoton Festival held in Lhasa, capital of Tibet Autonomous Region. /CGTN Photo

A Thangka painting exhibited during the week-long Shoton Festival held in Lhasa, capital of Tibet Autonomous Region. /CGTN Photo

Generally, one needs to go through several stages before they can master the craftsmanship, including sketching, coloring, gold application and painting the figure’s eyes, among other steps.

“After graduating from here, I want to go back home and teach Thangka to people there, as there are very few people know how to paint it,” the student said.

Traditionally, Thangka paintings were mostly made for monasteries and local believers. Today, the religious artwork is becoming increasingly popular among diversified groups, such as art collectors. Phuntsok says balancing market and tradition is a matter of concern.

A massive Thangka painting of Buddha, measuring 40 meters long and 37 meters wide, was displayed on the first day of the Shoton Festival. /CGTN Photo

A massive Thangka painting of Buddha, measuring 40 meters long and 37 meters wide, was displayed on the first day of the Shoton Festival. /CGTN Photo

“Without the market, the cultural heritage might disappear some day, as fewer and fewer people will learn it. But over-commercialization would also deprive the students and even painters of their own ideas and reverent attitude towards the art,” he said.

In recent years, more Thangka schools have been set up in Tibet and other areas, which is conducive to preserving the unique art form and passing it down. Punthsok says, while respecting tradition, some innovative attempts are necessary to maintain its vitality.

“Innovation is not destroying tradition. Tradition also evolves from innovation.”

(Cover image: Phuntsok works on a Thangka painting. His family has been dedicated to the traditional culture for generations. /CGTN Photo)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3