Opinions

15:22, 31-Jul-2018

Opinion: Can Zimbabwe rise like a phoenix from Mugabe’s ashes?

Updated

15:18, 03-Aug-2018

Busani Bafana

Editor’s Note: Busani Bafana is a Zimbabwean freelance journalist based in Bulawayo. He writes on social development, human rights, and science. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

For the first time, Zimbabweans are spoiled in their choices for a new leader.

For 37 years, Robert Mugabe was the only leader the country knew since its independence from Britain in 1980. Last November, Zimbabweans showed Mugabe the political door following an army-led coup and people took to the streets. Mugabe was out, but his legacy lingers on.

When the polling stations closed and the ballots are emptied for counting, the 5.6 million Zimbabweans who registered to vote will have chosen a new president, from a list of 23 contenders. Big bets are on two candidates who have dominated the presidential race: current president, 75-year-old Emmerson Mnangagwa of the ruling Zanu-PF and 40-year-old Nelson Chamisa, leader of the MDC Alliance.

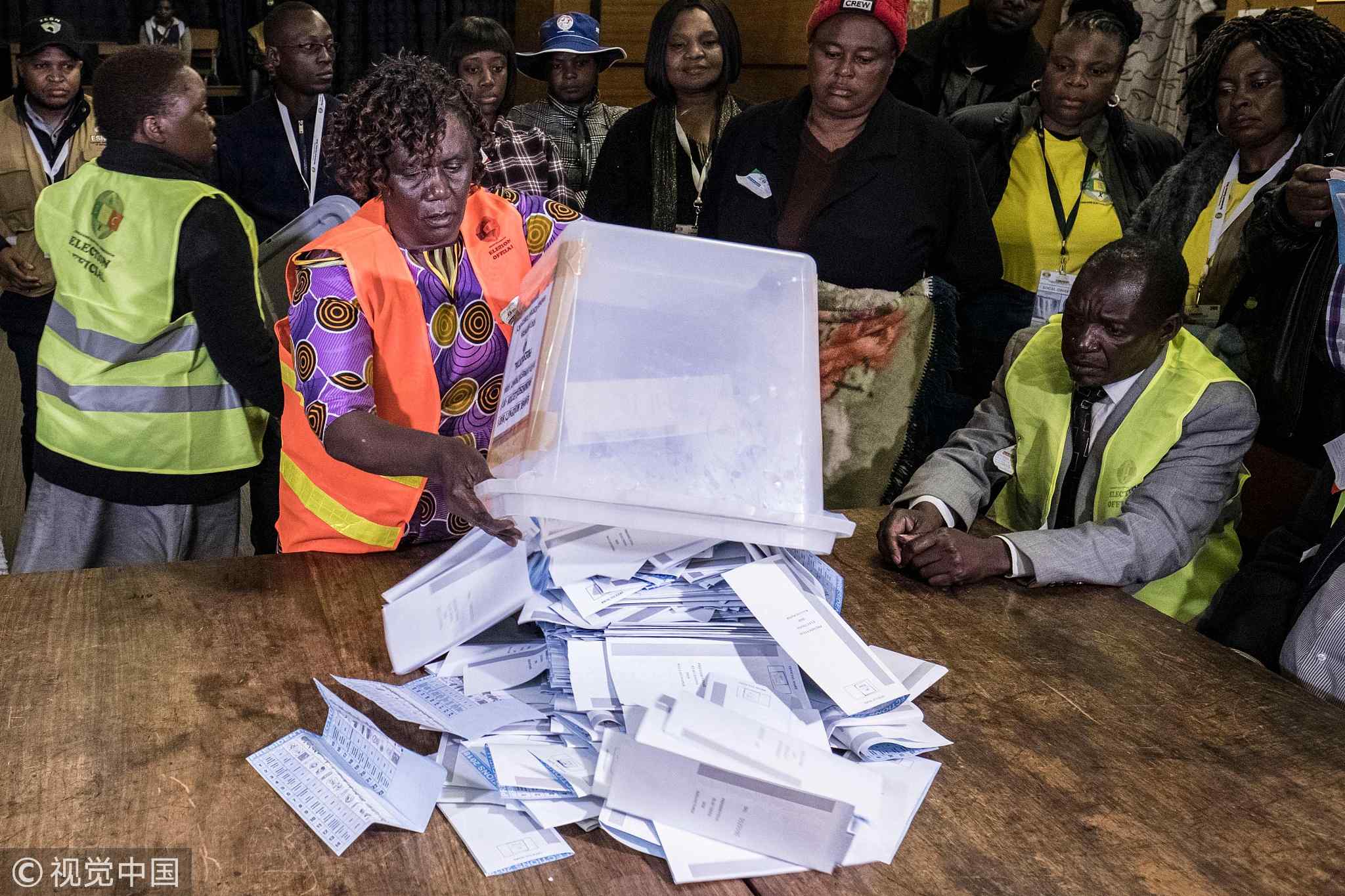

Electoral workers empty a presidential candidates ballot box onto a table during counting operations for Zimbabwe's general election at the David Livingston Primary school in central Harare on July 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

Electoral workers empty a presidential candidates ballot box onto a table during counting operations for Zimbabwe's general election at the David Livingston Primary school in central Harare on July 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

Pledging to bring jobs, improve education and health as well as luring foreign investment by restoring the economy, political candidates have promised much to an expectant citizenry that endured diminishing prospects under Mugabe’s reign. The elections presented a vote for change.

Mugabe took power in 1987 when he became executive president. He had cart Blanche in guiding the political and economic path of the country. A fervent revolutionary, Mugabe invested in the social development of the country following a brutal war of independence. He put reconciliation and nation-building on a public pedestal.

The list of political wishes from the electorate is long. On top is getting the economy right again. A free and fair poll is a template for building intentional good that will usher Zimbabwe into the international community of nations and more decisively, a ticket for international investors to come back to Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe has everything from mineral and natural resources, sound infrastructure, an educated and skilled manpower to boot. But it has the curse of corruption, cronyism, and divisions along party and ethnic lines which have affected the livelihoods of its people and isolated the country, a former investment jewel and net food producer in Africa.

According to the World Bank, Zimbabwe’s gross domestic product per capita in 2016 was about 1,009 US dollars and this is not rising. Unemployment has been estimated at 80 percent of the population, in a country with a 90 percent literacy rate, one of the highest in Africa, making poverty endemic.

Zimbabwean police officers gather and chat outside a polling station for the general election in the suburb of Mbare of Zimbabwe's capital Harare on July 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

Zimbabwean police officers gather and chat outside a polling station for the general election in the suburb of Mbare of Zimbabwe's capital Harare on July 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

The elections hold a promise to return Zimbabwe to normalcy. A 2018 research study by consulting firm, Emergent Research, predicted that a credible election will raise the country’s GDP by 6.5 percent and by 15 percent in 2019. Zimbabwe can be better if the new leader commits to building a new foundation with fresh blocks hewn from the country’s deep pool of talent and skills.

Restoring economic fundamentals is a priority, as is healing a divided nation. Banishing Mugabe’s legacy is possible but will take an astute leader, to build bridges between winners and losers. Reconciliation much talked about, but less acted on, will be a relations game changer in the post-election era.

In a recent conversation on the Zimbabwe elections, veteran British journalist and writer, Michael Holman, told me the 2018 elections could be the most important elections since 1962 when the Rhodesian Front came to power. Two years later, Ian Smith (former Rhodesian Prime Minister), declared the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain, unleashing a 15-year old civil war in the country which Holman told me led to the "worst violence in which thousands died and thousands became refugees."

Holman was the Financial Times Africa Editor from 1986 to 2001, a turning point before Zimbabwe slid into economic morass, and will hopefully be part of the past when the country welcomes a new leader in August.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3