Climate

13:14, 25-Dec-2018

TECH IT OUT: Giant clams, nature's climate archive

Updated

12:50, 28-Dec-2018

By Yang Zhao, Feng Ran, Ma Ke

05:46

People have many questions about global warming. How hot could this planet get? Has it ever been as warm as it is now? Is it getting warm faster than it did thousands of years ago? The data is very limited to answer these questions. Humans invented the thermometer only a century ago and set up weather stations around the same time.

But scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have discovered that the data from a set of animal proxies can potentially fill in some of these blanks.

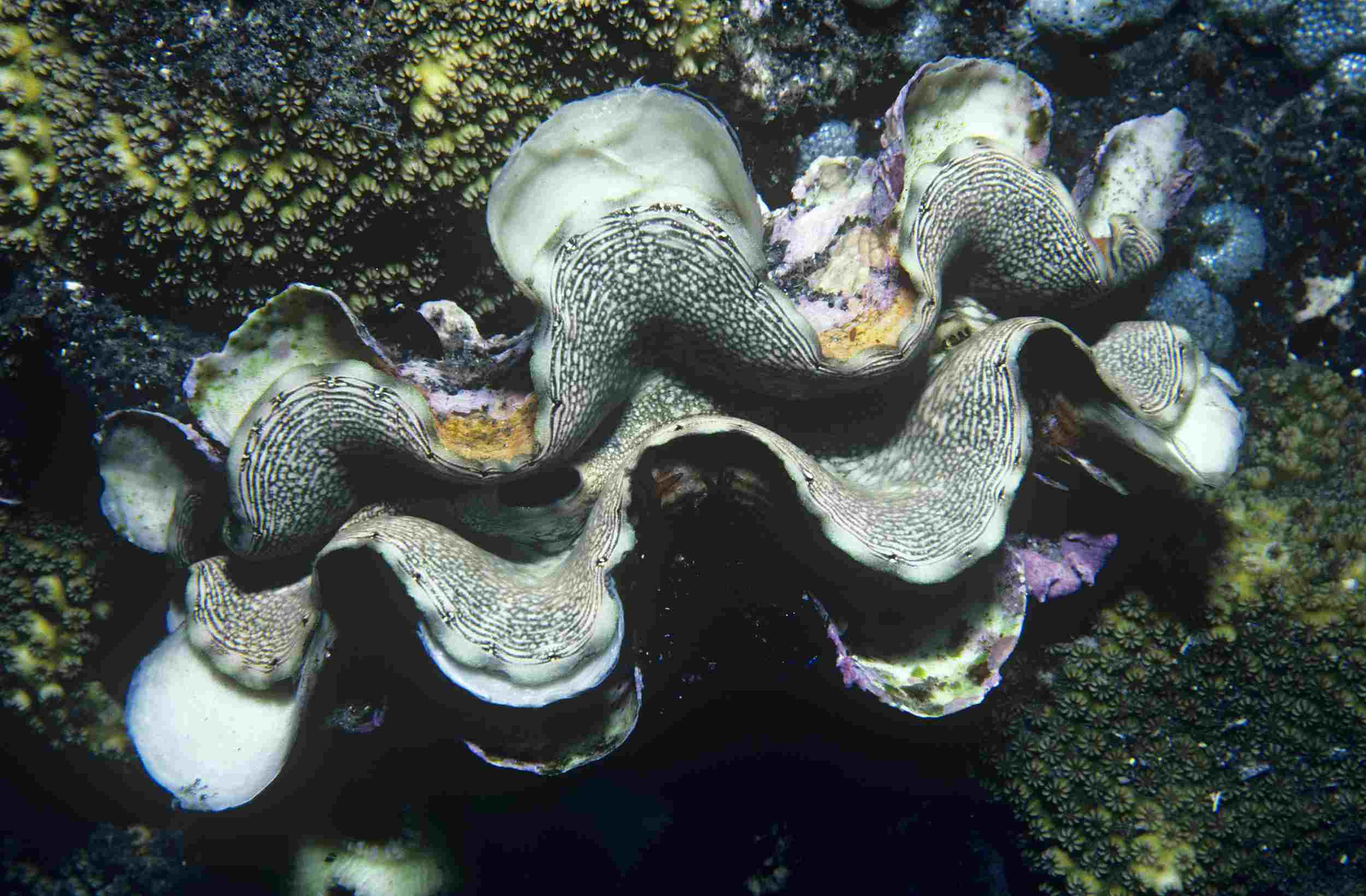

One of them is the giant clam, the largest mollusk on the planet.

A giant clam /VCG Photo

A giant clam /VCG Photo

Giant clams get only one chance to find a nice home. Once they fasten themselves onto a reef, there they sit for the rest of their lives.

Because of that, elements in the surrounding water can deposit and become a part of their shells through the nearly 100 years of their lifespan until the shells become a work of art.

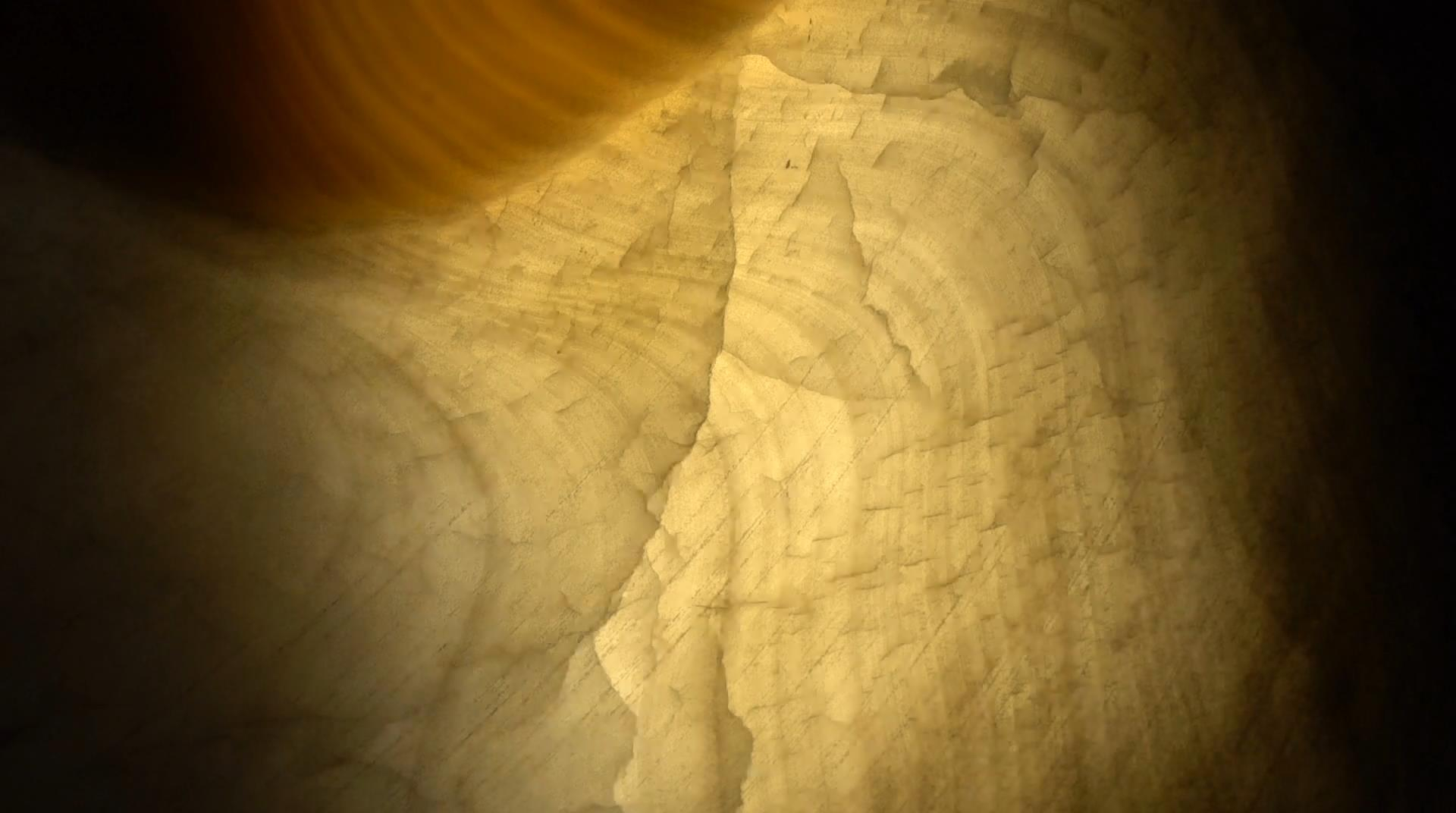

Giant clams have increments like tree rings. The time lapse between every two visible layers is approximately a year.

Parallel arcs on the hinge of a giant clam's shell resemble tree rings. /CGTN Photo

Parallel arcs on the hinge of a giant clam's shell resemble tree rings. /CGTN Photo

Hotter sea temperatures can drive up metabolism in giant clams. Wider increments mean warmer years, and thinner ones mean the opposite. However, the width of layers cannot help scientists calculate an exact sea temperature.

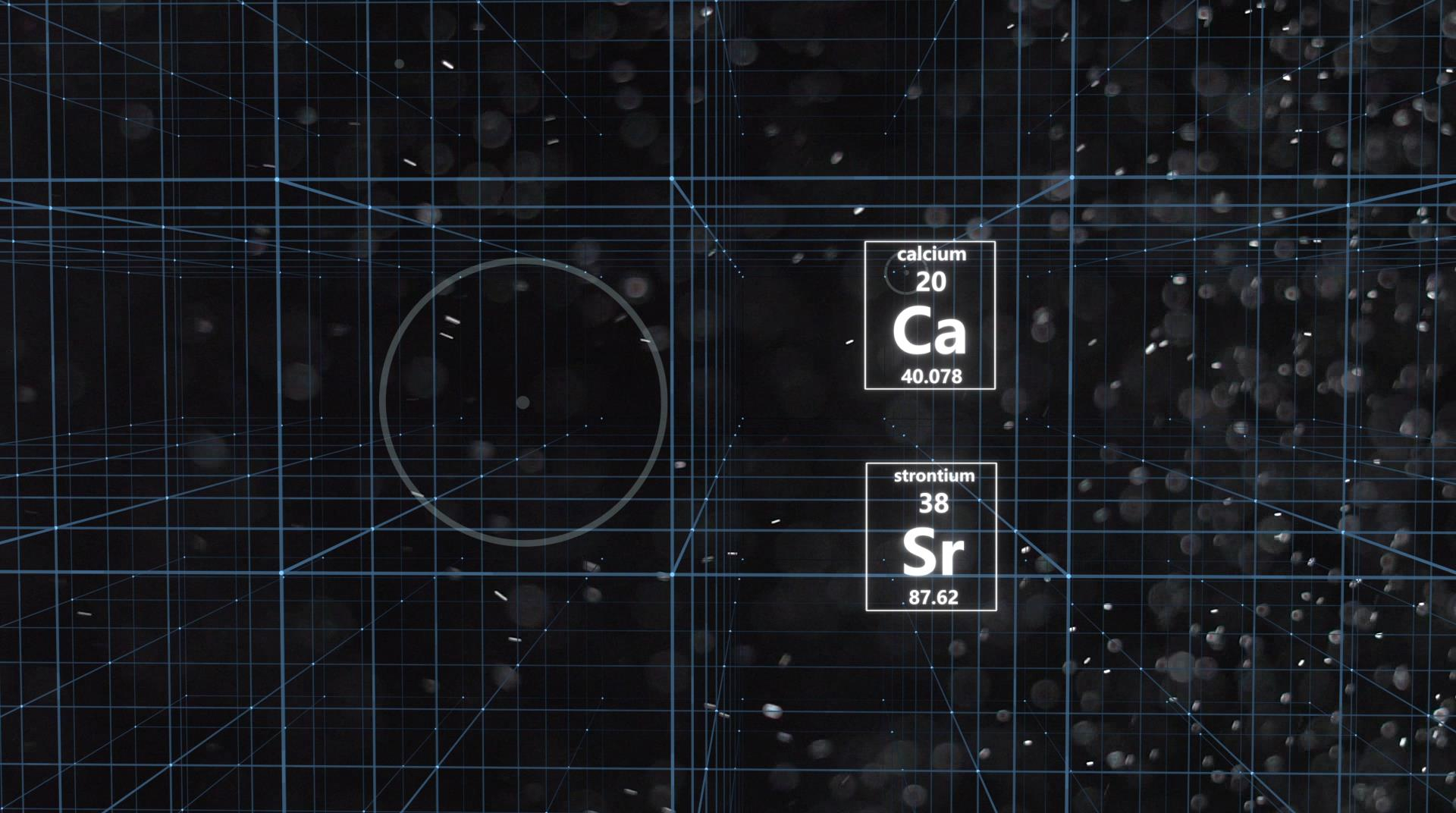

But two elements can! The shells of giant clams are made up of calcium carbonate. Strontium (Sr) belongs to the same chemical family as calcium (Ca). It replaces calcium during the formation of the calcium carbonate shells.

Scientists can perceive sea temperatures by calculating the ratio of strontium and calcium. /CGTN Photo

Scientists can perceive sea temperatures by calculating the ratio of strontium and calcium. /CGTN Photo

Professor Yan Hong said this substitution reaction is affected by temperature. He said scientists can use modern technologies to calibrate that process in order to find out what temperature leads to what Sr/Ca ratio.

Professor Yan Hong hopes giant clams can reveal the climate secret. /CGTN Photo

Professor Yan Hong hopes giant clams can reveal the climate secret. /CGTN Photo

By taking samples from its different layers, and measuring the ratio of strontium and calcium involved, scientists can reconstruct the temperature records and have a full picture of what the climate was like in the past.

They found out that around 1,000 years ago, during China's Song Dynasty, the earth's average temperature was higher by 0.7 degree Celsius as compared to now, which means the temperature now is still within the range of temperature variation of the past 1,000 years.

It also indicates that the earth is getting warmer at a faster pace than it did in that period.

But to unlock the secret of climate change, scientists need the clams to reveal more.

Professor Yan and his team had been digging deeper into the data of hourly Sr/Ca ratio when he told us that more detailed data can help study short-term weather events as well.

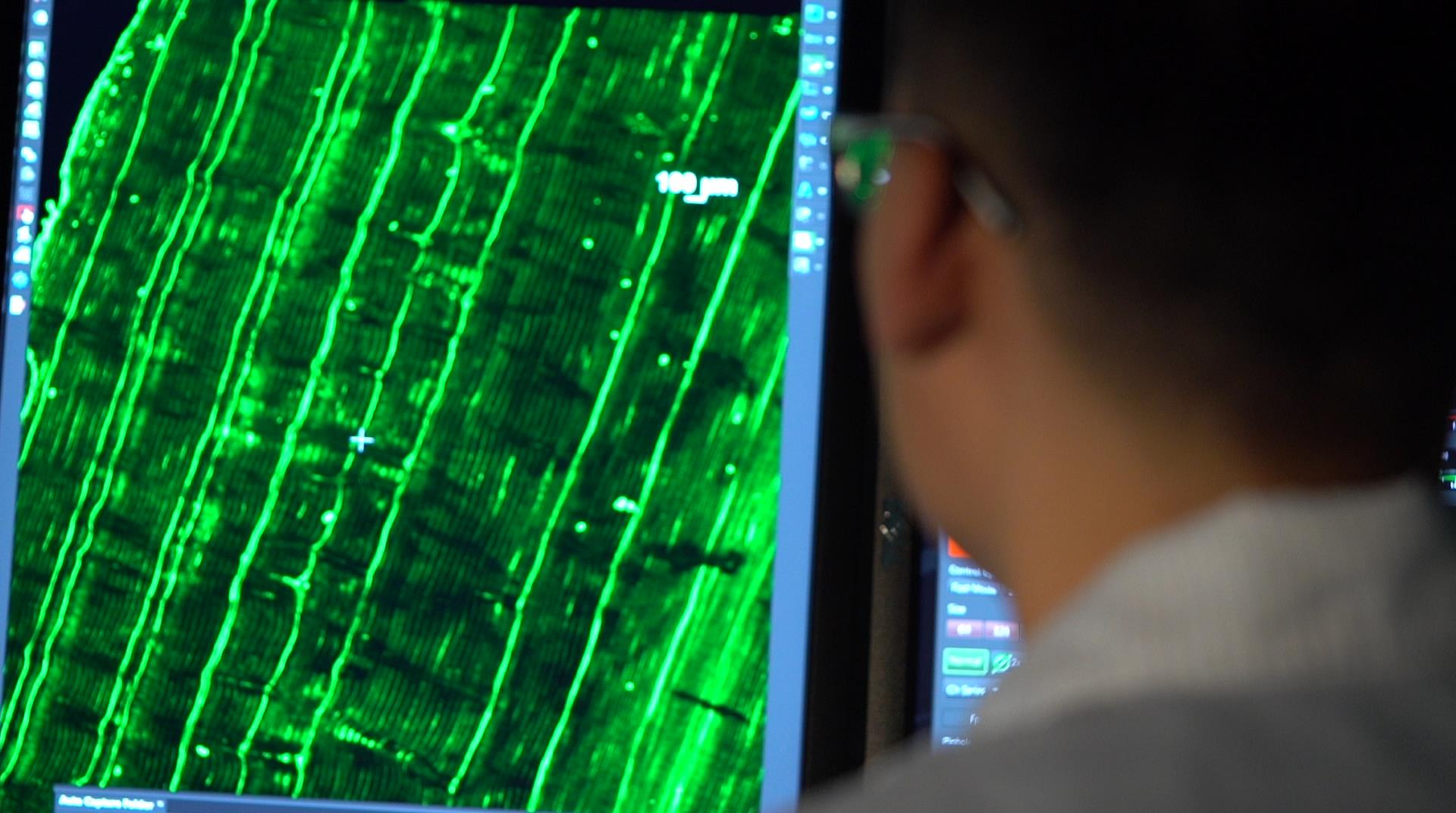

For that purpose, they decided to apply, for the first time, laser confocal microscope, which was initially designed to observe cells, into the study of the giant clams.

And the machine did not fail them.

Laser confocal microscope can reveal the daily-base increment. /CGTN Photo

Laser confocal microscope can reveal the daily-base increment. /CGTN Photo

One layer was zoomed into hundreds of parallel arcs, which are generally formed on a daily basis But when they try to measure the element ratio like before, something abnormal popped up.

Scientists detected a change in the content of barium and iron, which led to an interesting fact – a large amount of barium and iron would appear in the layers every once in a while.

Barium and iron are usually found on the much deeper seabed, while the giant clams' habitat is in the shallow sea.

So what could carry them from remote water all the way to the seashore?

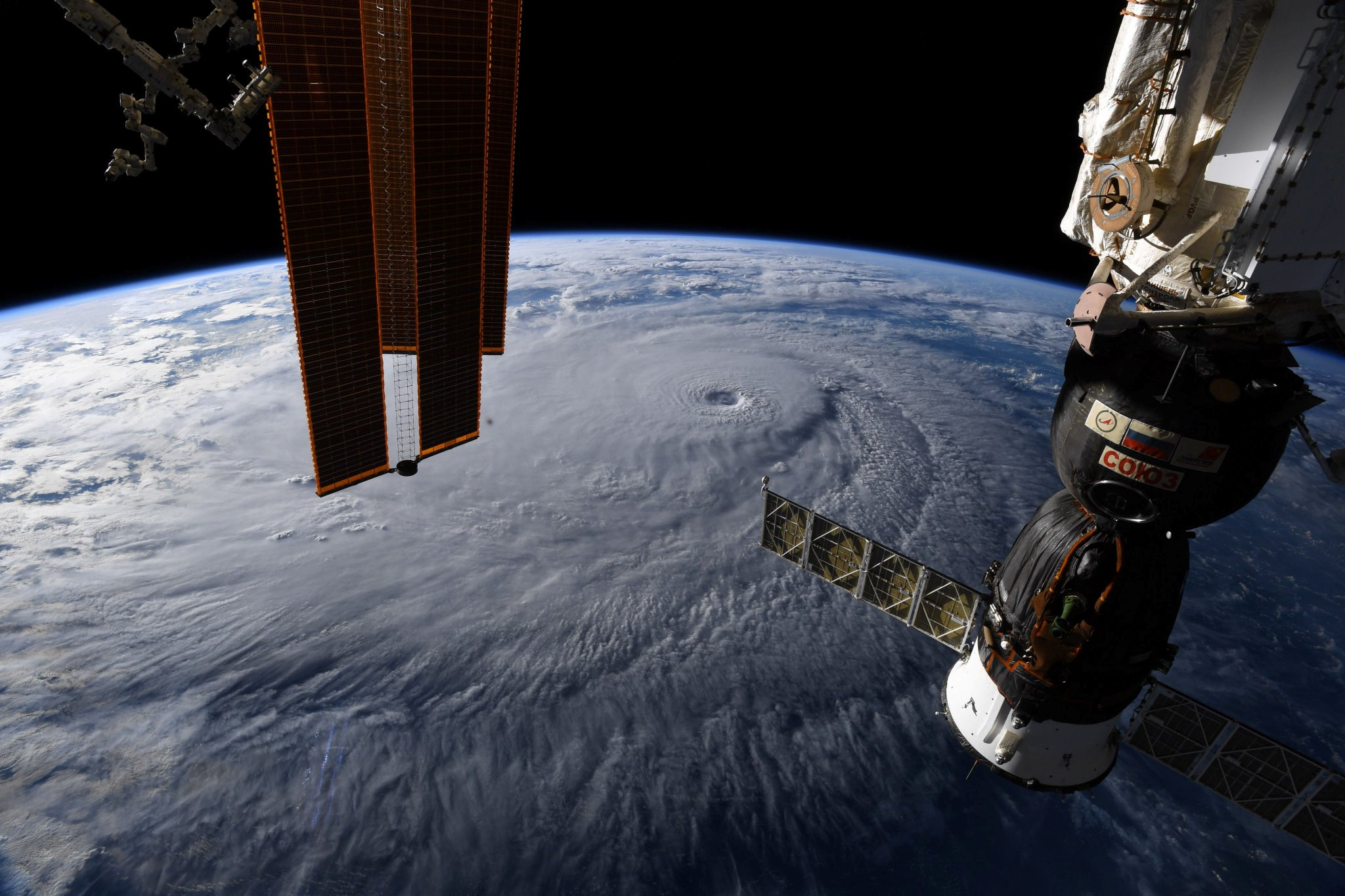

Powerful and quick: Yes, a typhoon.

A photo taken from the International Space Station shows Hurricane Lane near Hawaii, U.S., August 22, 2018. /VCG Photo

A photo taken from the International Space Station shows Hurricane Lane near Hawaii, U.S., August 22, 2018. /VCG Photo

Professor Yan speculated an exchange of substances between different layers of water under the force of strong winds. So barium and iron can be brought from the seabed up to the shallow waters, where the giant clams live.

What scientists are doing now is to find the giant clams or fossils which lived in the past warmer periods of the earth's history. Adding the typhoon records to that calendar may tell us if major storms will increase with global warming.

What his team is doing now is to ask nature for more data by collecting the giant clams from different historical periods and build a reliable database.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3