World

13:09, 23-Jun-2018

US Supreme Court: No tracking of phone location data without warrant

CGTN

Police need a warrant to access a person's mobile phone tracking data, the US Supreme Court ruled on Friday, in what has been hailed as a victory for digital privacy proponents.

Mobile phone users share their physical locations with telecoms companies with every call they make as they go about their day. In criminal investigations, US law enforcement officers could previously retrieve this data from a third party without a warrant under the Stored Communications Act. More than 100,000 of these requests were submitted to wireless carriers in 2016, according to tech website Cult of Mac.

However, in a razor-thin decision (5 to 4), the court said this common practice amounted to an unreasonable search and seizure under the US Constitution's Fourth Amendment, extending the right to privacy to the digital realm.

"We decline to grant the state unrestricted access to a wireless carrier’s database of physical location information," wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in his ruling.

"In light of the deeply revealing nature of [cell-site location information], its depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach, and the inescapable and automatic nature of its collection, the fact that such information is gathered by a third party does not make it any less deserving of Fourth Amendment protection."

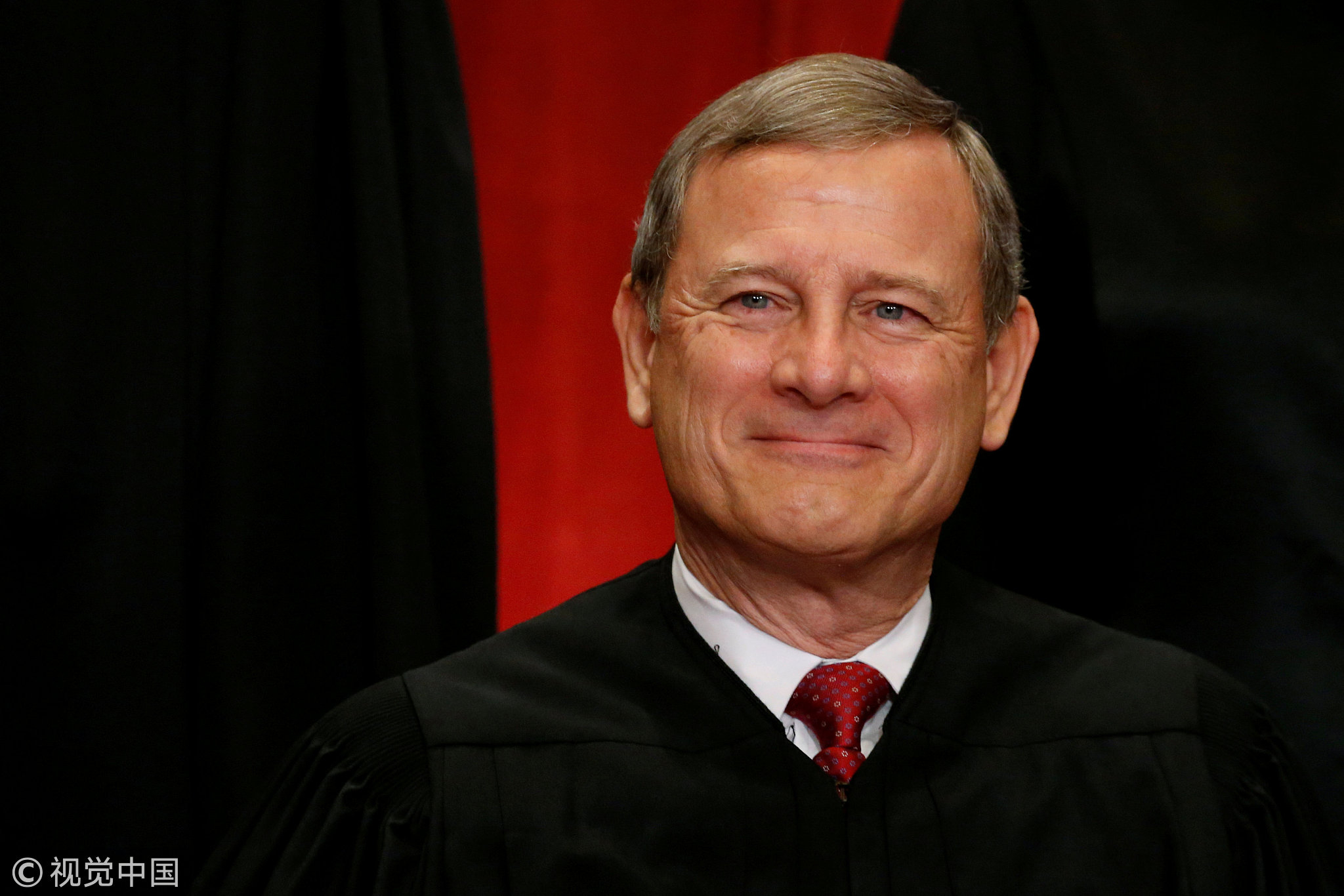

US Chief Justice John Roberts poses for a photo at the Supreme Court building in Washington, DC, June 1, 2017. /VCG Photo

US Chief Justice John Roberts poses for a photo at the Supreme Court building in Washington, DC, June 1, 2017. /VCG Photo

Carpenter v. United States

The court was ruling in the case of Timothy Carpenter, who was convicted in six armed robberies at Radio Shack and T-Mobile stores in Ohio and Michigan in 2013, owing in part to his cellphone location history.

Police helped establish that Carpenter was near the scene of the robberies by securing from his cellphone carrier his past "cell site location information" that tracks which cellphone towers relay calls. Unbeknownst to him, he had been sharing his location with the phone carrier, and the FBI managed to collect data spanning over 127 days and almost 12,900 geographical points, that linked him to the crime scenes.

Carpenter's lawyers during his trial argued that the location-based evidence should be excluded from the proceedings as they were illegally obtained, without a warrant. His bid to suppress the evidence failed, with the court at the time saying the man "lacked a reasonable expectation of privacy" as he had voluntarily handed over his information to the company.

However, Roberts ruled that "the Government’s position fails to contend with the seismic shifts in digital technology that made possible the tracking of not only Carpenter’s location but also everyone else’s, not for a short period but for years and years."

Despite the landmark decision, the verdict has its limitations and only concerns historical cellphone data.

Roberts said it does not prevent police from collecting other types of business records without warrants, or avoid warrants altogether in emergency situations. "Traditional surveillance techniques" such as security footage are not included in the ruling, which is also not concerned with whether access to real-time location information requires a court-ordered warrant.

Carpenter’s case will now return to lower courts. His conviction may not be overturned because other evidence also linked him to the crimes.

(With input from Reuters)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3