Politics

22:22, 20-Nov-2018

Brexit deadlock: Four months, seven scenarios

Updated

22:09, 23-Nov-2018

By John Goodrich

Britain has a little over four months to work out Brexit.

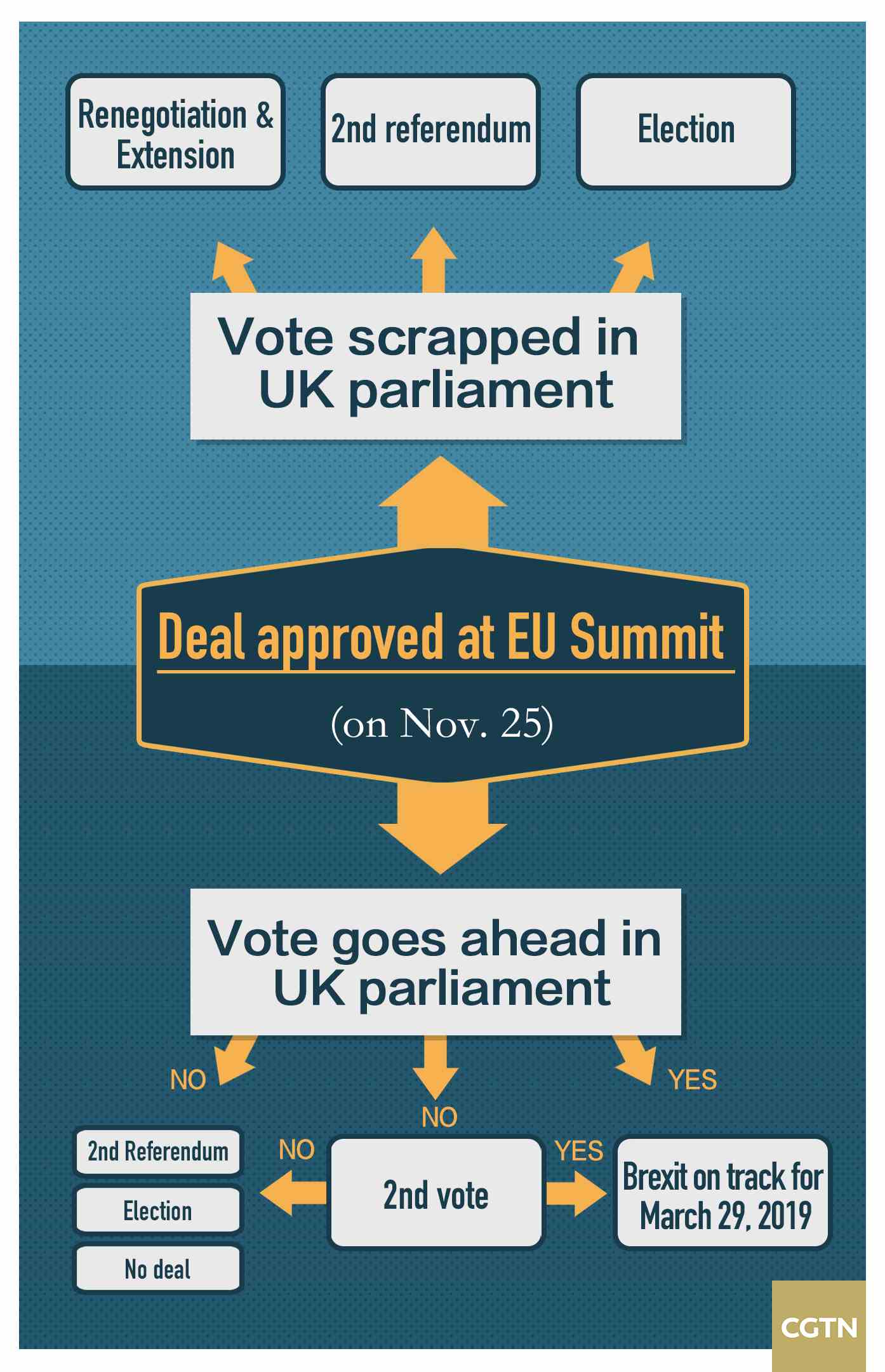

Despite recent drama, the process is really in a deadlock. With the ambiguity of Prime Minister Theresa May's plan broken by the publication of her withdrawal deal last week, it is clearer than ever that there is no majority for any option in Britain.

If nothing is decided before March 29, 2019 – beyond acceptance of a deal by other EU members – the country will drop out of the EU without any deal in place.

Attempted coups, talk of elections and referendums and a hardening of opinion against Prime Minister Theresa May from all sides have dominated headlines, but no one can say with certainty how, after more than two years of talks, the process will play out.

Here are seven of the most likely scenarios.

1. Yes to May's deal

The simplest solution and an increasingly unlikely option: Britain's parliament backs the withdrawal deal negotiated by May and the EU, leaves the bloc as scheduled on March 29, 2019, and enters a transition period in which negotiations over the future relationship are concluded.

No one likes May's agreement, but Brexit is incredibly complex, and this is the only deal on the table. The business community backs it as the least bad option, and as financial markets panic over a possible "no deal" an unsatisfying compromise might seem attractive to a majority of MPs.

2. No to May's deal

Governments rarely put anything to a vote if defeat is likely, and at present May doesn't have the 318 votes needed to pass her deal. At least 51 of her own Conservative MPs say they are opposed, her allies in government the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), plan to vote against and nearly all opposition politicians will go through the "no" lobby.

Downing Street reportedly hopes to push through the deal on a second vote once the reality of the alternatives set in, but could May survive an initial defeat? The opposition would likely call for a vote of no confidence, and without the DUP the government hasn't got a majority. A change of leader, a second referendum, a general election: two of the three would be firmly on the cards.

3. No deal

A "no deal" essentially means Britain would fall out of the EU on March 29, 2019. May's plan would have to be rejected or withdrawn for this to happen, but some pro-Brexit politicians see this as precisely what Britain voted for – a clean break with the EU.

Serious economic consequences for both Britain and the EU would likely follow such an outcome, and a majority of MPs from all sides would probably join forces to avert it, possibly by agreeing a delay with the EU. Time is short, however, and it can't be ruled out entirely.

4. Renegotiation and extension

Despite the fevered activity of the past week, Brexit is really in a deadlock. Movement will require change, and many in May's Conservative Party, including five prominent Cabinet ministers, and in the opposition want the withdrawal agreement to be renegotiated.

It is the least dramatic option, but beset by problems. Firstly, the EU has said it will not happen. Secondly, different camps in Britain still want different deals. And thirdly, even if a majority was found for an alternative plan and the EU was willing to renegotiate, time is short and it's unclear whether the March 29, 2019 exit deadline can be extended.

5. May is voted out

Conservative hardliners are plotting to get rid of May, but their attempts to force a vote of no confidence have stalled. Forty-eight MPs must formally request a vote, and despite promises from leaders of the group that has not happened.

It remains possible, particularly if the five senior pro-Brexit Cabinet ministers who are lobbying for the deal to be renegotiated quit. May is hoping ongoing negotiations over the future relationship – phase two of Brexit – will sway the doubters in her own party.

6. Second referendum

The drumbeat for a second referendum or "People's Vote" has grown louder over recent months. Campaigners against Brexit argue that the original campaign was dishonest and invalidates the result, those in favor insist going back to the people would be undemocratic.

May has been steadfastly opposed, and her deal would have to be rejected or withdrawn for it to become a possibility. MPs have been consistently wary of this option, which would open a new can of worms. To start with, what would the choices on the ballot be? But so long as the stalemate continues, the chances of a deadlock-breaking referendum grows.

7. General election

The second deadlock-breaking option is a general election. May could call a snap poll if she fails to pass her deal through parliament. The circumstances are different from 2017 when she lost her party's majority, but the scars of that experience mean it's unlikely to be repeated.

MPs could also force a change with a vote of no confidence in the government, not impossible with the DUP wavering over its support for the government. The opposition Labour Party has said it may call such a vote if May's deal is rejected in parliament.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3