Opinions

13:07, 27-Jul-2018

Opinion: What is crucial in the industrial policy debate?

Updated

12:16, 30-Jul-2018

Cheng Dawei

Editor’s Note: Cheng Dawei is a professor at School of Economics, Renmin University of China. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

There was a big debate on the industrial policy between two China’s famous economists, professor Zhang Weiying and Lin Yifu in 2016.

Professor Zhang believed that China is full of government failure, the government allocation of resources and the allocation resources of private sectors are different, the government is not sensitive to market signals, thus industrial policy damages market efficiency.

When Professor Lin talked about industrial policy, it implies that the government’s goal is the public’s goal, once the government’s goal is achieved, the public welfare is improved.

Renewed interest in industrial policy has emerged recently in the context of China-US trade war. The US thinks that China’s economic development policy calls for China to develop and become global leaders in at least 10 key strategic emerging industries, including artificial intelligence, integrated circuits, aircraft and other high tech sectors.

Even though President Trump talks about the trade deficit, in fact, the US-China trade war is about industrial policy.

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

What is industrial policy? In the long debate on industrial policy, some researchers have given their answers.

Dani Rodirk, professor (2004) at Harvard University thinks the right way of thinking of industrial policy is as a discovery process -— one where firms and the government learn about underlying costs and opportunities and engage in strategic coordination.

Professor Rodirk thinks innovation in the developing world is constrained not on the supply side but on the demand side. That is, it is not the lack of trained scientists and engineers, or inadequate protection of intellectual property that restricts the innovations that are needed to restructure low-income economies.

Innovation is undercut instead by lack of demand from its potential users in the real economy—the entrepreneurs. And the demand for innovation is low in turn because entrepreneurs perceive new activities to have low profitability.

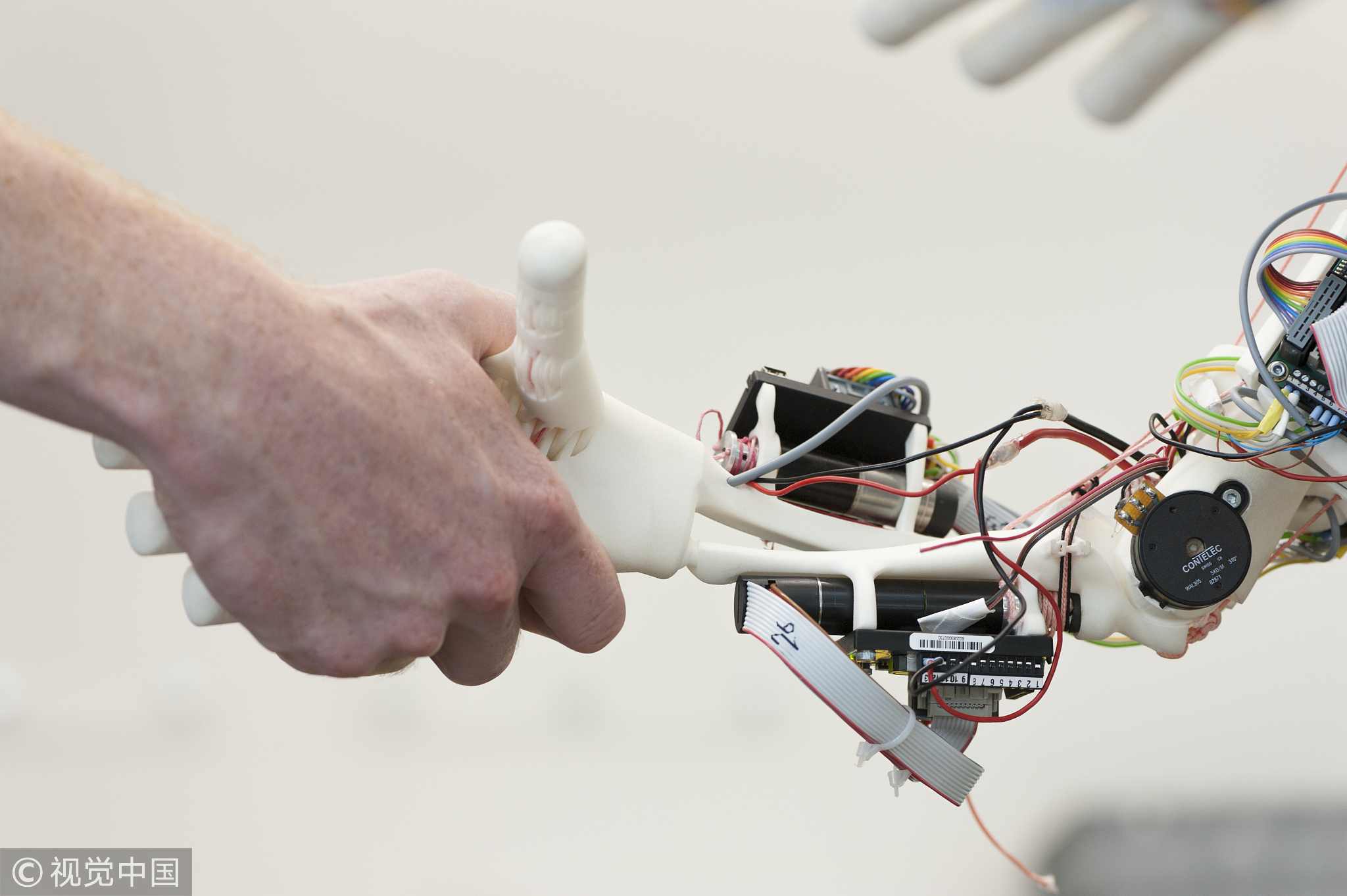

ROBOY humanoid robot /VCG Photo

ROBOY humanoid robot /VCG Photo

Kinger and Lederman (2004) also provided evidence on market failures that restrict self-discovery. They found that their measure of self-discovery in a country (the number of new products being exported) is positively associated with the height of entry barriers. Thus, above scholars believe the need for industrial policy.

Yes, the reality is it is true that countries, especially developing countries need to embed private initiatives in a framework of government policies. Industrial policy does work. Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is one of the world’s leading science and technology think tanks.

During US-China trade war, ITIF supports President Trump’s policy. In April this year, ITIF issued a report called “Why Manufacturing Digitalization Matters and How Countries Are Supporting It”.

The report studies how digitization is transforming manufacturing globally and how firms especially small-to medium-sized enterprise (SME) need support. The report examines support programs and policies of ten nations—Argentina, Australia, Austria, Canada, China, Germany, Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Yes, China’s 2025 plan was listed on the report.

From the report, we also can see the other 9 nations are using industrial policies to promote digital innovation. For example, the report mentions Japan operates several initiatives designed to prepare the nation for an advanced manufacturing future. In June 2015, Japan government launched the Industrial Value Chains Initiative (IVI), a forum promoting the development and adoption of smart manufacturing solutions.

So, I think the real crucial question of the industrial policy debate is not about whether a country can use industrial policy or not, it is how to use it. In this regard, it is crucial for the government to make an effective industrial policy. The lack of policy making capabilities is a cause of industrial policy failure in many countries. China of course needs to improve its capability.

References:

1) Dani Rodirk, “Industrial Policy for the Twenty-first Century“, UNIDO, September 2004.

2) Kinger and Lederman, “Discovery and Development: An Empirical Exploration of new products”, World Bank, August 2004.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3