Opinions

19:21, 16-Oct-2018

Palliative care: What traditional medical treatment doesn’t provide

Updated

18:39, 19-Oct-2018

CGTN’s The Point

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of both patients and their families when faced with life-threatening illness. In comparison with traditional medical treatments, which emphasize curing the diseases, palliative care advocates for pain relief and allows them to die peacefully.

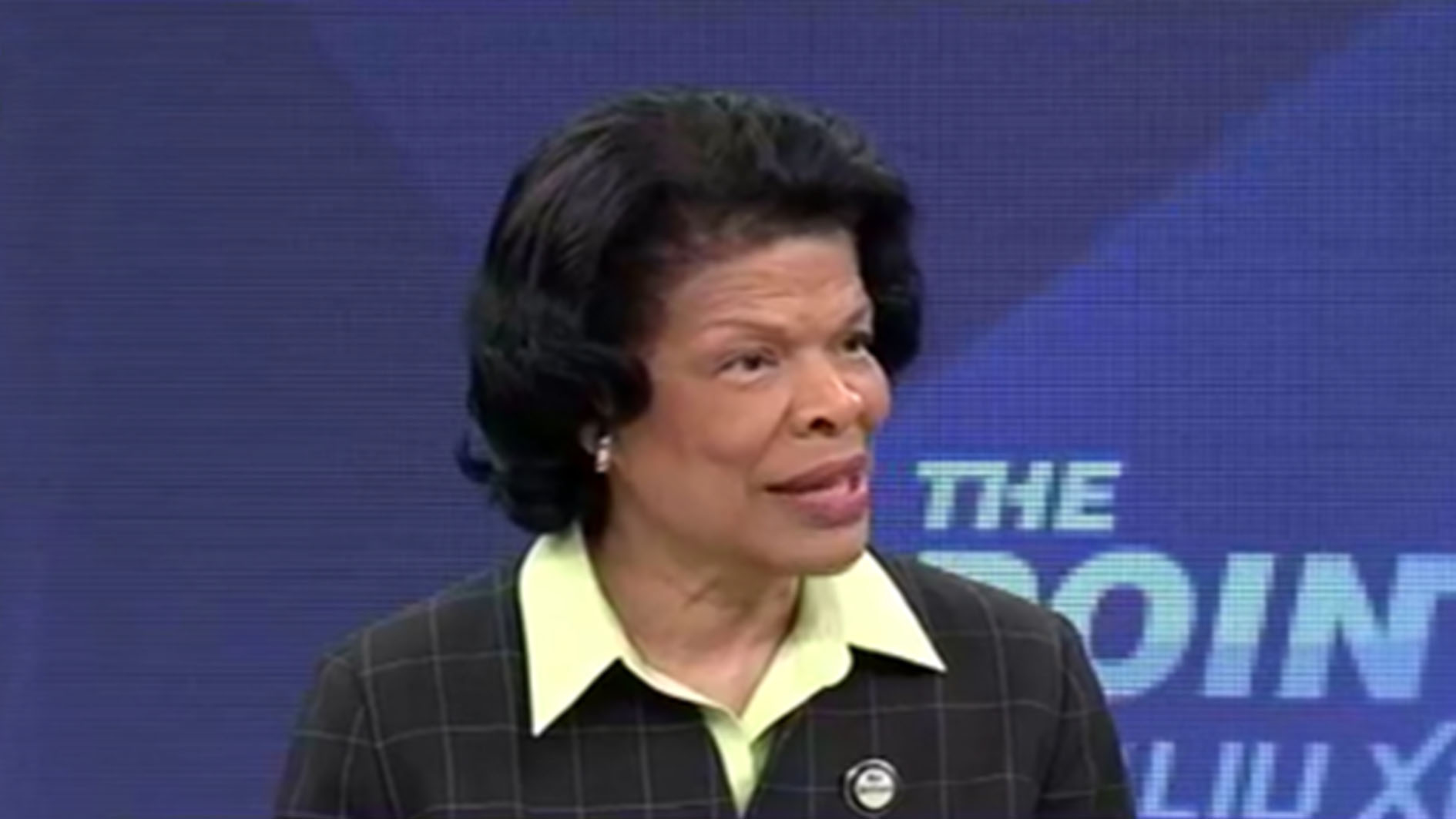

“Rather than thinking only medicine, only pharmacy, we can think broader than that,” said Deforia Lane, an associate director of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland, US who also works as a music therapist. She promotes music therapy in her palliative care treatment.

01:43

“The National Institutes of Health and The Joint Commission – which is the organization that provides guidelines for all hospitals in order for them to be certified in the United States – they wrote into their guidelines the necessity of having non-pharmacological treatments for patients,” said Lane.

Jennifer Philip, the chair of the Department of Palliative Medicine at the University of Melbourne, agreed with Lane, pointing out the limits of medicine. “Those limits of medicine can be a cause of suffering rather than an amelioration of suffering,” she explained.

00:39

Philip also corrected the misconception of palliative care. “Some people think that it's an either-or... you either have treatment or you have palliative care. We can deliver cancer treatment and palliative care at the same time,” she said.

The Chinese government published its first time official guidelines mapping out the standards and provisions for the administration of hospice and palliative care in January 2017. Over a year later. what changes have occurred?

00:56

Ning Xiaohong, associate professor in the Geriatric Department of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, said “more and more doctors and nurses, and the government began to understand the importance of palliative care”.

“A big change in China is that the government has chosen five cities: Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, Changchun, and Zhengzhou to try to practice palliative care,” added Ning.

She also addressed the things needed to be improved in China. One is about better educating the doctors and nurses to teach them “how to give those patients a good death” and the other is about educating the whole of society “to let people know there is a choice when they are facing death.”

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3