World

09:28, 23-Mar-2019

Roadblocks in Brexit explained: the Irish border and Gibraltar

By Yu Jing

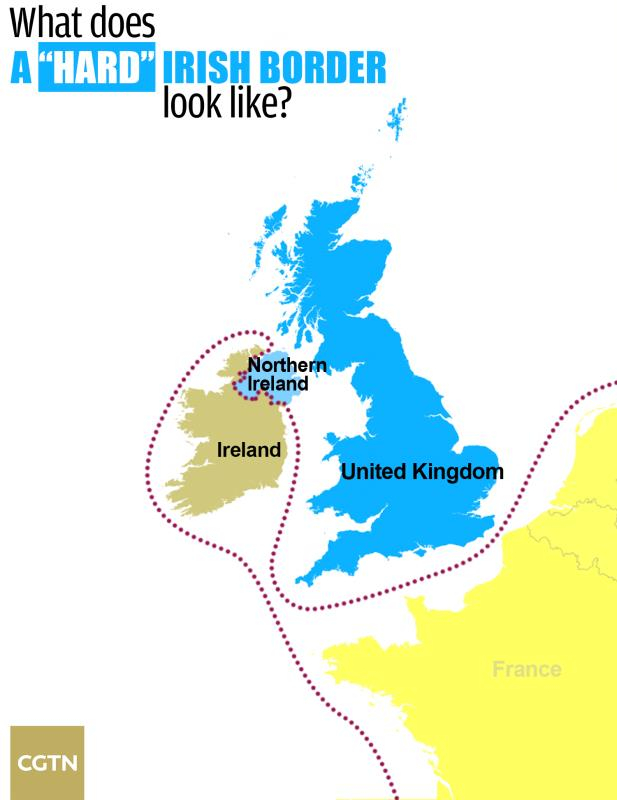

The Irish border, once a symbol of hard-earned peace and political reconciliation, is now at the heart of the Brexit deadlock.

The 310-mile-long border which separates Northern Ireland, a part of the UK, from the Republic of Ireland, an EU member country, will become the only land border that separates the UK from the EU after Brexit.

This essentially means that Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland will follow different trade standards; products and free movement of people between the two will end. This would create the need for custom checkpoints at the border. For a region with a recent history of bloodshed and conflict, a hard borderline is feared to reignite simmering tension in the region.

A brief history of the tenuous relationship

The freedom to move across the border is central to the peace agreement signed in 1998 that ended the 30-year-old conflict in Northern Ireland.

A "hard" Irish border. /CGTN Photo

A "hard" Irish border. /CGTN Photo

Conflicts between Irish nationalists, mostly composed of Catholics and pro-British Protestants, had killed 3,600 people. The peace agreement mandated a power-sharing agreement between the two. Paramilitary groups in exchange agreed to disarm.

Previously, under EU's freedom of movement principle, goods and people could travel across the border freely though Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland are separate countries. The fear is that once Northern Ireland pulls out from the EU, custom checkpoints need to reinstalled on the border.

It is feared that a hard border would unravel the fragile peace in Northern Ireland. Twenty years after the peace agreement was signed, tensions at the border persist. Customs checks at the border would easily become target of attack from nationalist paramilitary groups.

May's difficult balancing act

Due to May's loss in a snap general election in 2017, the Conservatives' minority government required political support from one Northern Irish party, the Democratic Union Party (DUP) to pass legislation.

Theresa May addresses the nation after asking the EU for a Brexit extension, March 20, 2019. /VCG Photo

Theresa May addresses the nation after asking the EU for a Brexit extension, March 20, 2019. /VCG Photo

The DUP, from the very beginning, made clear that it has two bottom lines when it comes to the situation after Brexit. One, a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland cannot be reinstalled. Second, the trade barrier between Northern Ireland and Britain needs to be as minimal as possible.

May once proposed to maintain "regulatory alignment" between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, but the proposal was vetoed by the DUP citing fear that it would pave the way for Northern Ireland's further separation from Britain because Northern Ireland and Britain would follow different trade standards.

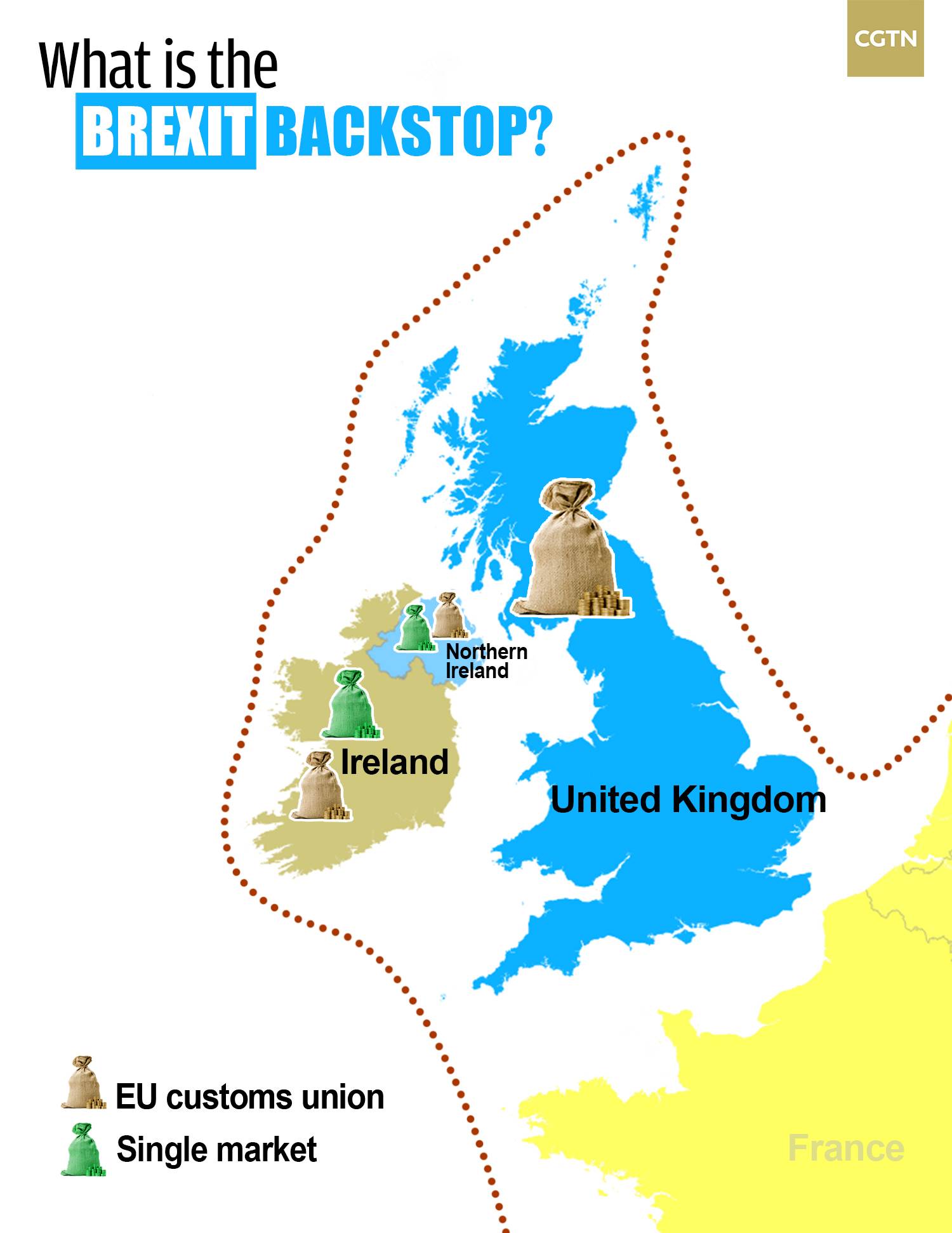

Since May made clear that a physical border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland had to be avoided, the EU proposed a "backstop" provision – as long as there is no long-term trade pact, Britain will remain in the EU customs union and Northern Ireland, in addition, will also be bound by rules of the single market. This essentially prevents a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The Brexit backstop. /CGTN Photo

The Brexit backstop. /CGTN Photo

But the backstop turned out to be a plan that pleased no one. Brexiteers worried it would keep the UK tied to EU rules indefinitely. Unionist in Northern Ireland were concerned that an implicit border in the Irish Sea would become a slippery slope for Northern Ireland to separate from the UK.

May is caught between a rock and a hard place. While the EU refused to renegotiate the deal, the UK Parliament has already voted down the deal twice. In order to avoid a "no-deal Brexit", May has to secure backing from the Parliament.

Wait, there is another deadline over border

Let us zoom in to a small peninsula at the southern tip of Spain, Gibraltar, where another contention of the Brexit debate lies.

A map of Gibraltar. /CGTN Photo

A map of Gibraltar. /CGTN Photo

Gibraltar has been controlled by Britain since 1713, but Spain continues to claim sovereignty over the peninsula. Gibraltar is due to leave the EU along with the UK though an overwhelming majority of the population voted to stay in the EU during the referendum in 2016.

An estimated 12,000 workers cross the border between mainland Spain and Gibraltar each day. An open border with Spain gives Gibraltar access to European markets and a closure of the border would have devastating effect on Gibraltar's economy.

But the Spanish government insisted that it must have a say over the future trade or security deals of Gibraltar and threatened to veto May's Brexit deal. As the deadline to sign the deal approached, the UK government acknowledged that any future economic agreement involving Gibraltar would have to be negotiated separately.

Just as everyone thought that the issue of Gibraltar is about to be resolved, a footnote in a proposed law on UK travelling rights reignited the debate. In a contingency plan for travel arrangement under a "no-deal Brexit" drafted by the EU, a footnote referred to Gibraltar as "a colony of the British crown" – a way that favors Spain's interpretation of the status of Gibraltar –rather than "a British overseas territory", as the UK government calls it.

The latest development shows that President of the European Council Donald Tusk announced that the EU will only back a short extension of the deadline if May's Brexit deal passes in Parliament next week. As all eyes are on May to save the UK from a "no-deal Brexit", the blame game is likely to continue.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3