Opinions

10:46, 21-Nov-2018

Opinion: The West doesn't get BRI's appeal to developing nations

Updated

10:20, 24-Nov-2018

By Tom Fowdy

Editor's note: Tom Fowdy is a UK-based political analyst. The article reflects the author's views, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

The APEC meetings last week saw an attempt by the United States to hijack the discussions with a charged offensive against the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

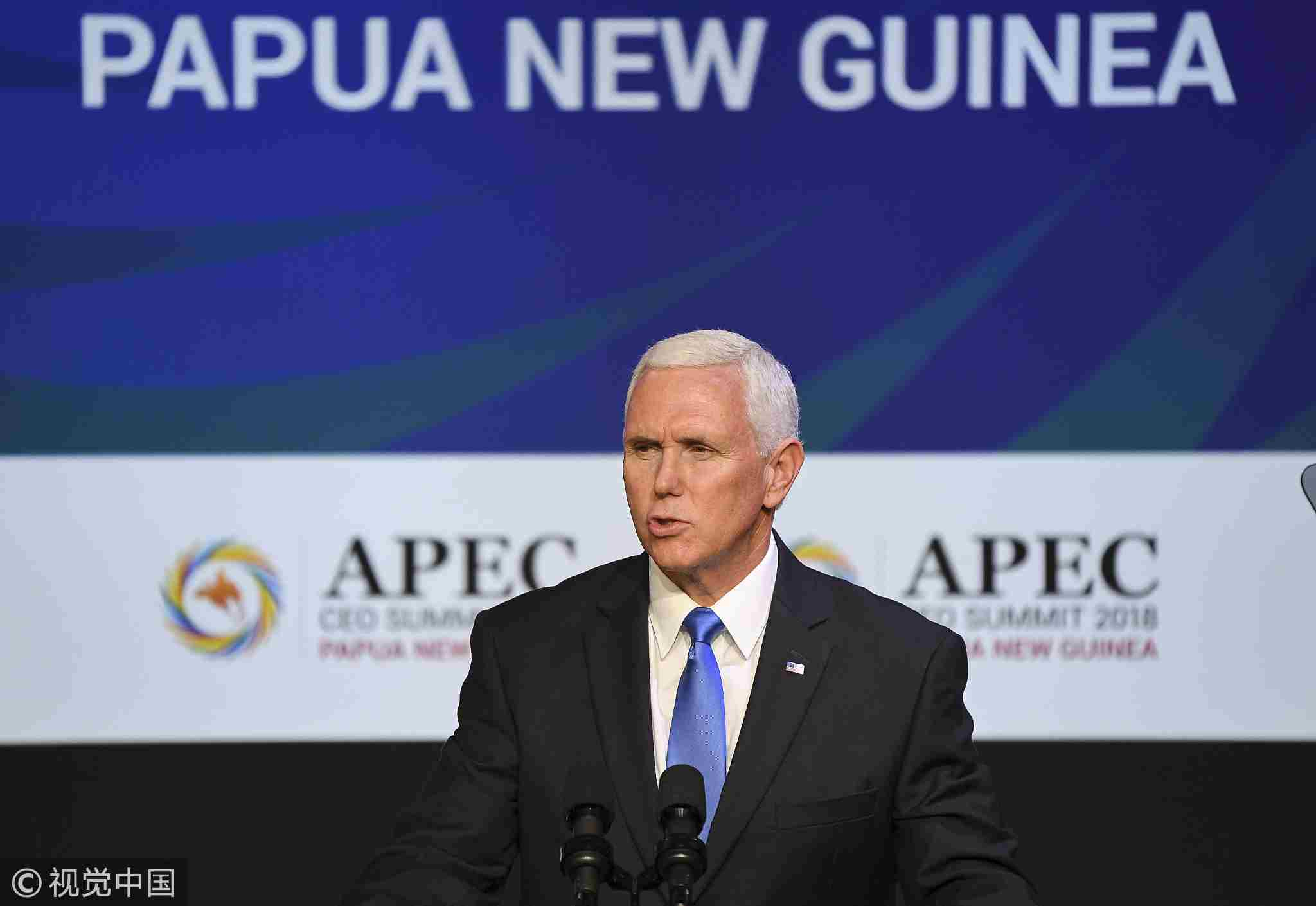

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence drew from a wider set of U.S. political narratives which deemed China's scheme as debt trap diplomacy and a means of coercion, urging South Pacific nations to instead side with Washington.

The western media largely followed suit with this depiction, attempting to frame the meetings as a setback for China and as usual, attempting to portray the BRI in cynical discourses related to power and coercion.

This co-exists with the banal and often unchallenged belief that because of their purported values, the West is the real “champion” of the developing world and always come with the “right intentions.”

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence speaks at the APEC CEO Summit in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, November 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence speaks at the APEC CEO Summit in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, November 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

Such thinking, however, serves to deny history itself that being the West's very own legacy in the developing world.

To subsequently dismiss BRI on the grounds of “geopolitical coercion” is to ignore and dismiss the background as to why so many nations have chosen to turn to China for development assistance, a reality which they cannot bring themselves to acknowledge.

To better explain this, we will move away from the APEC event itself and instead, look towards Africa as a case study in how Western neoliberal policies have in fact worked to the detriment rather than the supposed benefit of developing countries.

In the 1970s, African nations turned to Western financial and international organizations for loans and development assistance. It was a time of sweeping economic change around the world, with a new consensus emerging that free markets were ultimately superior in attaining economic growth than state-led socialist policies.

According to Asad Imi, who wrote a report on the IMF's impact on the developing world in 2004, such institutions would spearhead the advance of neo-liberalism into such countries.

They gained a perfect opportunity and by the 80s, many of these nations, for example, Zambia, suffered from debt crises which forced them to submit to demands from international bodies, most importantly what was known as “structural adjustment programs” (SAPs).

SAPs essentially sought to impose neo-liberal economic models upon their recipients, dismantling state initiatives such as the subsidy and support of industry and state welfare.

All government money was to be redirected towards paying debt, while in addition all barriers were removed to a fully open, global market. Up to 36 African countries would sign up to them.

Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, July 18, 2018 /VCG Photo

Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, July 18, 2018 /VCG Photo

However, the aspirations of the IMF and other institutions were largely ideological rather than practical; they did not give heed to Africa's political realities. The sudden forced opening of Africa's economies to western markets did not stimulate growth, but in fact, undermined them with exposure to competition they could not handle.

As Imi's work shows, this saw an amplification of poverty throughout not just Africa, but the entire developing world.

Real wages halved, unemployment soared and the number of people pushed into severe poverty increased by the millions. His report then notes that Africa's GDP fell by 15 percent from 1980-2000. Per capita income on average in 1990, the same as it was in 1960.

Some countries even suffered famines. As G.K Helleiner, a financial analyst in the 1980s noted, the imposition of such measures saw imports and consumption tumble, creating economic stagnation and decay.

Subsequently, this had political consequences, the programs of the international monetary fund created widespread resentment in the African continent, leading to riots and political pushbacks.

Turning to American ways did not benefit Africa, just like the days of European colonialism. This opened the door to China.

The 5th China-Africa People's Forum was held in Chengdu, China, July 24, 2018. /VCG Photo.

The 5th China-Africa People's Forum was held in Chengdu, China, July 24, 2018. /VCG Photo.

As a country that has successfully shown a road to its own development, as well as one that had also suffered previously at the hands of western economic exploitation, Beijing offered an alternative to the continent under the banner of the Third World.

Building upon the famous Bandung solidarity of the 1950s, China approached these countries with the view of treating them as equals, not subjects.

Consequentially, it has offered Africa developmental assistance which has not come with ideological strings; Chinese exports to the continent have allowed Africa to benefit from cheap consumerism that Western policies decimated in the 1980s. It has also helped them develop new export markets.

As a result, China's programs and investments in Africa have spearheaded a new era of economic growth throughout the continent and rapid infrastructure development. It has allowed these nations to escape the ideological demands and debt traps of the West and has given them options which in turn have given them increased political space.

The BRI particularly has given Africa a strong vision for its economic future, allowing nations to orient their infrastructure and exports towards specific uses that will only hasten its development.

Yet, the U.S. and Europe fail to comprehend why the BRI and broader economic ties with China have been appealing to the developing world.

They fail to recognize that the forced imposition of a western-centric model in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America was ultimately detrimental to the people of those regions and instead empowered a select club of elites.

Now, a growing number of countries have decided to look beyond the west for sources of prosperity and development, daring to step outside of the American financial order. To subsequently claim that China is guilty of “debt traps” and “coercion” is thus to deny the very reasons why the BRI has proven so popular in the first place.

It is time to stop patronizing and pointing fingers.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3