Business

13:24, 03-Jul-2018

Are Asian and African football caught in the 'middle income trap'?

Updated

13:04, 06-Jul-2018

CGTN

Russia hasn't been a happy hunting ground for teams from Asia and Africa.

Japan was knocked out of the World Cup by Belgium last night, meaning every team from Asia and Africa, the world’s most populated areas, has now officially bowed out of international football's biggest event.

None of the five African teams survived the group stage and Japan, the only Asian side that made it to the knockout phase this year, tied with Senegal on points but qualified because they had two fewer yellow cards.

Neymar Jr celebrates victory following the 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia Round of 16 match between Brazil and Mexico at Samara Arena on July 2, 2018, in Samara, Russia. /VCG Photo

Neymar Jr celebrates victory following the 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia Round of 16 match between Brazil and Mexico at Samara Arena on July 2, 2018, in Samara, Russia. /VCG Photo

Almost two decades into the 21st century and the trophy is still being safely rotated through the European and South American teams. Asian nations have fared slightly better at the event than their African counterparts during this period: S. Korea reached the semi-final in 2002. This year, they were eliminated in the group stage.

The 2002 result in Seoul didn’t bring in any kind of power restructuring to the World Cup. No Asian or African teams have advanced further than the quarterfinal in the following four tournaments. Since South Africa 2010, prospects have actually been getting worse. S. Korea and Japan managed to break into the round of 16 in 2010 and Ghana moved one step further. Four years later in Brazil, Algeria and Nigeria kept the flag flying for African football after their Asian peers were eliminated early, only to find themselves eliminated in the round of 16 by Germany and France respectively.

Japan reaching the quarterfinal this summer and their persistence in the game – they were beaten in the very last minute – together with S. Korea’s 2-0 win over Germany in their final group stage game has helped boost Asian football’s reputation, but the continent is still no closer to really vying for the trophy.

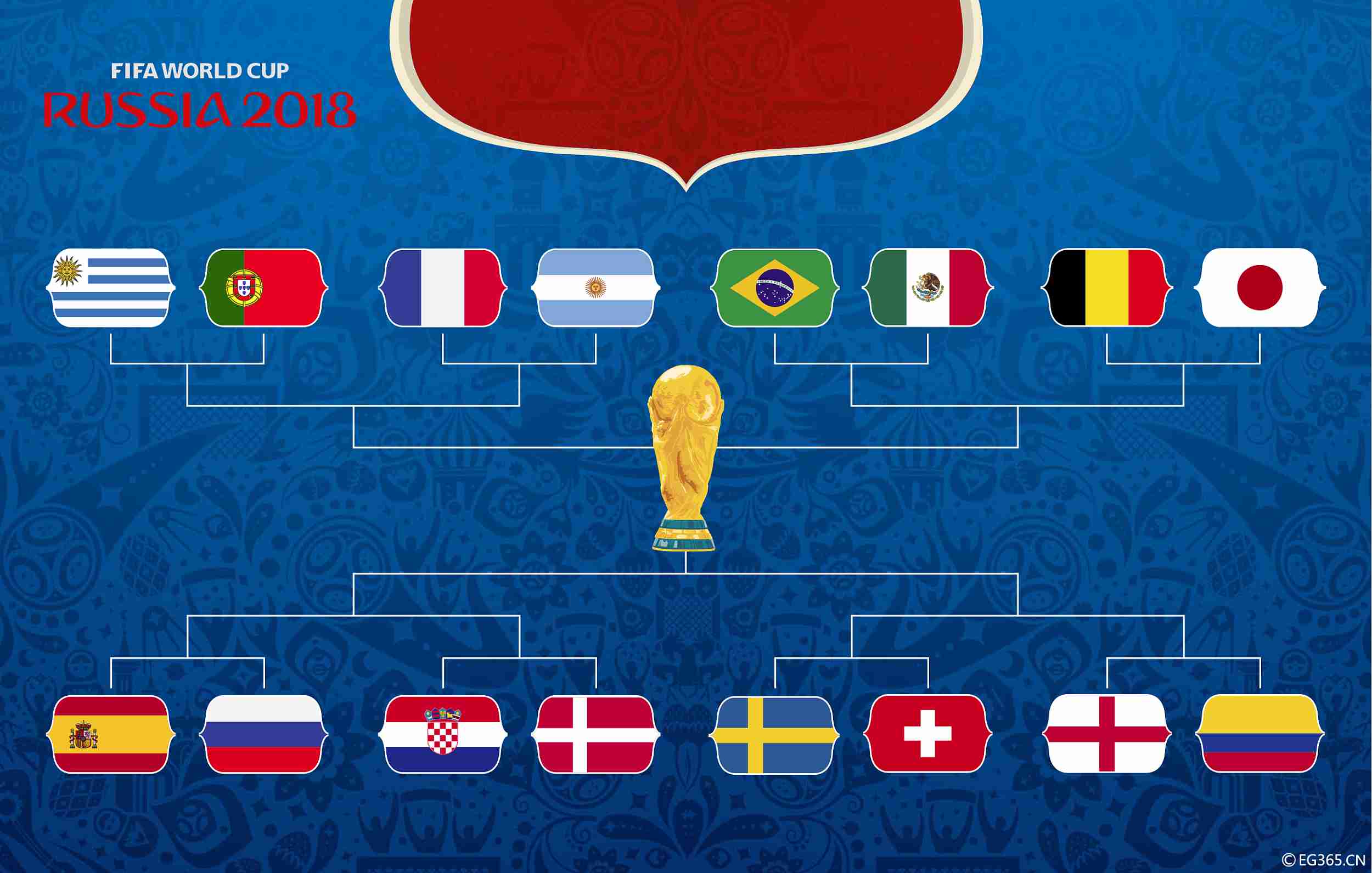

The Group of 16 /VCG Photo

The Group of 16 /VCG Photo

As of July 3, 2018, the rift on the FIFA global rankings between the traditional strongholds and the challengers is still notable. With the exception of Central America's Mexico in 15th place, the top 20 teams are either from Europe or South America. Tunisia, which is in northern Africa, comes in at 21 and Senegal are 27th. The highest ranking Asian country is Iran at 37. S. Korea, the third best in the Asian Football Confederation (AFC), is trailing at 57th globally and Japan four positions behind them. Australia, which joined the AFC from the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) in 2006, are 36.

Asian and African football advanced significantly on the global stage during the second half of the 20th Century, but has since struggled to further close the gap with the established nations in recent years – a pattern that economists may find familiar, as emerging markets are also struggling to equal developed countries.

Japan's Eiji Kawashima concedes as Belgium's Jan Vertonghen scores their first goal. /VCG Photo

Japan's Eiji Kawashima concedes as Belgium's Jan Vertonghen scores their first goal. /VCG Photo

Melanie Krause of Germany’s Hamburg University and Stefan Szymanski of the University of Michigan published a paper in 2017, titled "Convergence vs. the middle income trap: The case of global soccer," in which they claim that there is an analogue worth drawing between success in football and the success of an economic sector within a country.

Combing through more than 25,000 games played out between nations through 1950 to 2014, the two researchers found an “unconditional convergence” in global football that may explain how developing national teams were able to catch up so quickly, but also reveals that the sport has its own version of the middle income trap – a set of factors that cause growth to slow down rather than speed up.

The “convergence hypothesis” supposes that poorer economies tend to realize a higher rate of income growth than rich ones because their margin for productivity increases is larger, thus narrowing the income gap between the two groups until hitting the “middle income trap” wherein the emerging economy loses its competitive advantages, such as cheap labor. If the convergence is “unconditional” the rift closes in “on itself” naturally. But, while the theory may sound alluring, it only seems to work when comparing manufacturing sectors.

Goalkeeper Francis Uzoho of Nigeria in action during the 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia Group D match between Nigeria and Argentina at the Saint Petersburg Stadium in St. Petersburg, Russia, June 26, 2018. /Getty Images Photo

Goalkeeper Francis Uzoho of Nigeria in action during the 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia Group D match between Nigeria and Argentina at the Saint Petersburg Stadium in St. Petersburg, Russia, June 26, 2018. /Getty Images Photo

“It is obvious that for very weak teams, performance improvements are easier to achieve than for teams in the middle. Starting at low levels, better sports infrastructure, better nutrition and fitness plans, more effective training techniques, expanded knowledge of tactics and insights from abroad, gained by players or a foreign coach, can go a long way."

One of the underlying factors that drive the “unconditional convergence” in the sport, the two authors argue, is the increasing globalization of football: “The global nature of soccer facilitates the transfer of technology and skills. Weaker teams can catch up by adopting stronger nations’ training and talent selection techniques and by investing in their sports infrastructure.”

Additionally, a globalized player and coach market lubricates the free movement of talents from weaker nations to the world’s top domestic leagues. When they return to the national team, the benefit is obvious. Furthermore, the global governance of football helps unify the rules. No matter where the teams come from, when they play, they do it under a mutually recognizable framework.

However, according to the paper, after the low-hanging fruits have been picked by capital investment, reaching for higher targets can be demanding in different ways. Being caught in the “middle income trap for football” does not mean the force of globalization would start working against the weaker teams.

It may instead demand deeper integration, as “relatively good teams from Africa or Asia can gain less from regional integration where they meet even weaker peers. They simply have fewer opportunities to hone their skills against the world’s top national teams, becoming stuck in the soccer analogue of the middle income trap. This calls for stronger integration not only within but also between regions, an argument which can easily be made for other industries as well."

Japan reaching the quarterfinal this summer and their persistence in the game – they were beaten in the very last minute – together with S. Korea’s 2-0 win over Germany in their final group stage game has helped boost Asian football’s reputation, but the continent is still no closer to really vying for the trophy.

The theory sounds alluring, but it only seems to work when comparing manufacturing sectors.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3