Culture

21:35, 19-Jun-2018

New exhibition analyzes Silk Road's influence on the West

By Li Qiong

03:32

An exhibition at the National Museum of China “Embracing the Orient and the Occident: When the Silk Road Meets the Renaissance” is rediscovering Chinese-inspired elements hidden in Italian Renaissance art, and re-examining Western influence on Chinese art.

Cultural exchanges between China and Italy during the 13th to the 16th centuries are considered significant to the artistic evolution of both countries.

For more than 2,000 years, the Silk Road has facilitated frequent exchanges between the East and the West. Travelers, camels and ships which once traveled that route are of course gone now, but their legacies are left in exquisite works of art.

"These sculptures paint a scene of a Northern barbarian in ancient China training a dancing horse along the Silk Road," Li Jun, the exhibition's curator, pointed out. "Horse dancing was popular among the Persians, and was introduced to Chinese royal families during the Tang Dynasty (618-907)."

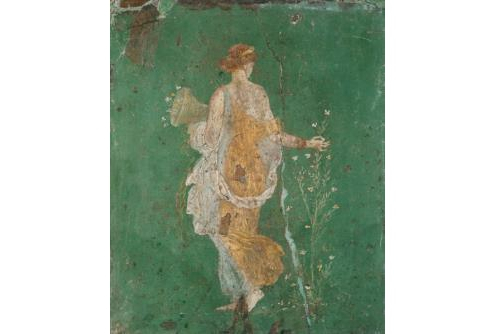

"Fresco Flora" discovered at Pompeii /Photo via National Museum of China

"Fresco Flora" discovered at Pompeii /Photo via National Museum of China

"In the 15th century, exchanges between China and Rome were frequent. Chinese silk became popular among the royal family and the rich in Rome. This picture titled 'Fresco Flora' was discovered in a room in Pompeii. She's wearing silk, imported from China."

The beginning of the Italian Renaissance was not only a process parallel to the introduction, consumption, imitation and re-creation of silk, but also the stories that took place on the Silk Road. Goods and maps on display show how significant the Chinese invention of the compass was in expeditions after it was introduced to the West.

Compass from the 17th century /Photo via National Museum of China

Compass from the 17th century /Photo via National Museum of China

In the 13th century, European travelers like Marco Polo were able to travel to the East with the aid of the compasses and nautical charts. They witnessed the prosperity of China’s economy and culture in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). And years later when they returned to Europe, they found cities like Venice were experiencing its own revolution during the European Renaissance.

Much of the iconography of both cultures appear similar at some point. For example, "The Madonna and Child" is one of the most famous images in Christian art, while "Guanyin with a child" is also an equally important icon in Chinese folk tradition.

Scroll painting “child-giving Guanyin” (L), “Madonna Salus Populi Romani in Santa Maria Maggiore” (R) /Photo via National Museum of China

Scroll painting “child-giving Guanyin” (L), “Madonna Salus Populi Romani in Santa Maria Maggiore” (R) /Photo via National Museum of China

"It's the first time the National Museum of China carried out a comparison between Chinese and foreign cultural relics of the same period," said Wei Na from the Department of Exhibition Planning and Fine Arts.

"Curator Li Jun went to Italy to view collections at different museums. There were some relics unavailable for the exhibition but are important, so we used replicas. The National Museum of China also collected relevant pieces from domestic museums like the Palace Museum and Inner Mongolia Museum. The entire process took us more than a month."

The exhibition runs through Aug. 19 at the National Museum of China.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3