Domestic

17:25, 30-Jan-2019

Young, middle class and childless: Behind China's declining birth rates

Updated

18:37, 30-Jan-2019

By Zhou Minxi

At 29, Dong Shuo is not in any hurry to get married and start a family.

The marketing executive at a tech company said he is not dating now and is preparing to study abroad.

Unlike their parents' generation, a growing number of young Chinese professionals like Dong do not have marriage and children at the top of their priority lists.

Dong said his parents are not too worried about it. Even though the dreaded age of 30 is not considered a disaster for single men as it is for single women in China, Dong said he felt it might be the last chance to do the things he always wanted to do before settling down.

"I think marriage is great, and children are important in our lives. But it comes with responsibilities. It means you can't act immature anymore," he said.

Demographic 'crisis' looming

The trend of China's one-child generation delaying marriage and child birth is well reflected by statistics.

China's population growth hit a historic low in 2018, two years after the country scrapped its decades-long one-child policy, according to official data.

A new green paper published earlier this month acknowledged a looming "demographic crisis," and forecast a negative population growth to begin around 2030.

Although the demographic dividend of the world's most populous country has not run out yet, China's population is aging faster than those in the rest of the world, including Europe and Japan. This presents a number of challenges for the economy.

"The population dividend has been crucial to China's economic development. A shrinking labor force means paying into the pension program will be a problem, and there won't be enough young people to support the elderly. That's unsustainable for the economy in the long run," said Professor Lu Jiehua at Peking University, the vice president of the China Population Association.

"A country full of old people will lose its innovative edge and cultural vitality. All of that is going to have an adverse effect on the economy," Lu said.

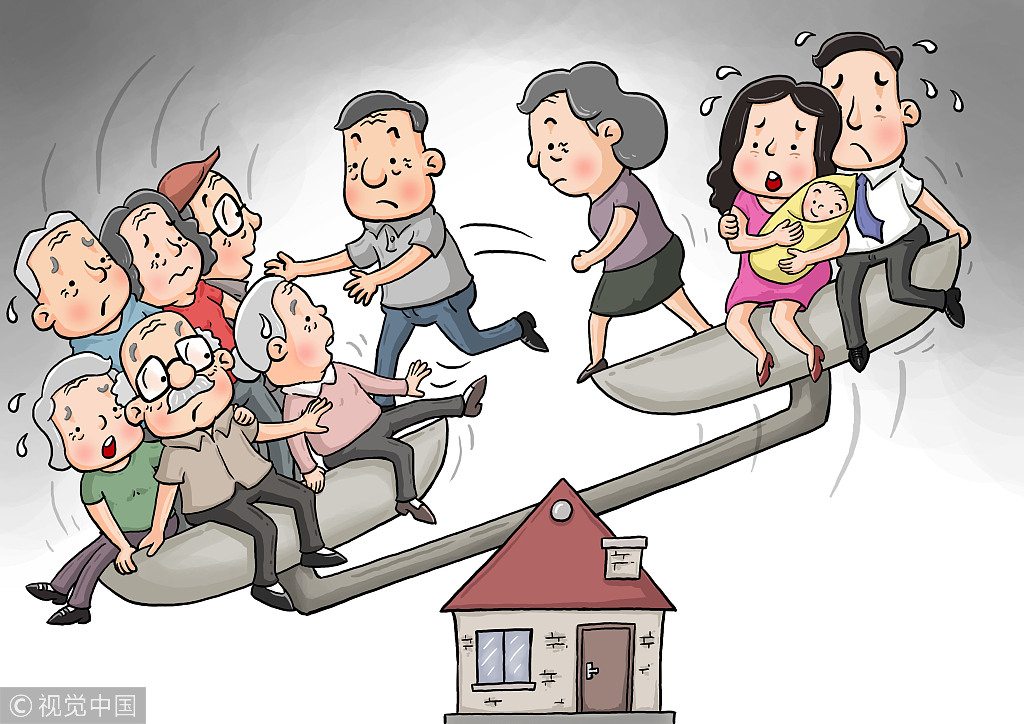

China is facing a rapidly aging society. /VCG Photo

China is facing a rapidly aging society. /VCG Photo

The "comprehensive two-child policy" allowing all Chinese couples to have two children saw a brief boost in new births the year after it took effect. But as it turned out, the relaxed policy produced far fewer babies than policy makers had expected.

Dong said he wants to have a child eventually but will not be swayed by any policy change.

Others, including many married couples, worry about the impact having children will have on their quality of life.

35-year-old English teacher Du Lan had her son in 2011, and has decided that she will not have a second child. Du said she didn't want her personal life to be squeezed further, as one child was already a handful.

"Another child would mean I can't do anything with my life for another three to four years," Du said. "I don't want my life to just revolve around children."

"It's like you are back to square one."

Women opting out

China has one of the highest labor force participation rates for women at 63 percent, according to the World Bank. Women in China contribute some 41 percent to the country's GDP, more than their counterparts in any other country, including those in North America.

While the economic realities have changed, the cultural expectations for Chinese women have largely remained the same. This means most married women have to juggle a full-time job and the traditional role of being a wife and mother. To make things worse, many companies tend to favor male candidates when hiring, as women of childbearing age are viewed by employers as a liability.

Feeling underappreciated at home and discriminated in the job market, educated Chinese women are increasingly putting marriage and motherhood on hold, or opting out altogether. Others are faced with the dilemma of choosing between family and career.

Ashley and her husband both work in the demanding financial industry. Now well into her thirties, she admitted that she's been too busy to think about having children.

"Before 30 I worked overtime almost every day, often till 10 p.m. or midnight. Having kids was out of the question," Ashley said.

"They don't like it if you get pregnant," she said, referring to a number of investment banks she has worked for where jobs are highly coveted. "There is too much competition, especially from younger colleagues. These are hard times. I could lose my job if I can't keep up."

Her hard work has paid off in other areas of life. When they are not putting in long hours at the office, the couple likes to splurge on exotic vacations.

"If we had a baby, we wouldn't be able to travel as much as we like. We enjoy our freedom," she said.

Census data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows China will face a 44 percent drop in women capable of childbearing in the next decade, thanks to a traditional preference for boys over girls in the country during the decades of the one-child policy. Meanwhile, the number of single women over the age of 30 exploded from less than 500,000 in 1990 to nearly six million in 2015, a trend that's likely to continue. All signs are pointing to a further plunge in birth rates down the road.

A Chinese mother is seen with her young child in the city. /VCG Photo

A Chinese mother is seen with her young child in the city. /VCG Photo

Living for yourself?

In a country where family lineage carries cultural significance, the delaying of marriage and parenthood – or abandoning them – is bound to lead to friction between generations.

Mr. Jin is one of those more traditional-minded older Chinese who have expressed dismay at the burgeoning individualism of millennials. The 60-year-old charity worker believes China's family planning policies had been a miscalculation of the situation, but insists that millennials' individualistic attitude – a by-product of Western consumerism – is the real cause behind China's demographic decline.

"Today's 20- and 30-somethings only think for themselves," Mr. Jin said. "Their attitudes toward family is not like previous generations." He added that the costs of living are not a concern for people who wish to have children.

"Now they think they can enjoy a Westernized lifestyle while being doted on as the only child by their parents," Mr. Jin said of those without children, "but when they are old and alone, with no siblings or children, they are going to regret it."

Traditionally, it was important for Chinese families to have many children, especially sons, who will care for their parents in old age. Now with improved social security, depending on family ties for support is becoming a thing of the past. But culturally ingrained ideas are not going away anytime soon.

"It's in Chinese culture for three or four generations of a family to be together under one roof. That's what makes us happy spiritually," Mr. Jin said.

Related story: Will the Year of the Pig bring more births to China?

Official attempts to discourage the single and childless lifestyle have been floated, and backfired spectacularly. Last year, a newspaper article proposing a "birth fund" went viral for all the wrong reasons, with netizens nationwide responding to the suggestion with shock and ridicule. Understood to be a punitive measure against single and childless people, the controversial proposal provoked soul searching and discussions about the values of individual lives.

On Zhihu, a Quora-like Chinese site, a post in reply to the question "what do people without children think?" concludes: "It's not because we are irresponsible. On the contrary, we are cautious because we are in awe of human life. We want to be responsible for our own and other people's lives. It's out of love, not selfishness."

The post received more than 6,800 upvotes from other users.

Professor Lu believes the lack of will to procreate is the inevitable result of economic and social developments, and how to better adapt to these new realities is what people should think about.

"The urbanization and modernization process in China will naturally bring down the birth rates," Lu said. "People's thinking needs to change, because the aging society is a future and a reality we must prepare for. That means improving supporting facilities and services."

Lu also noted that keeping the birth rates above the replacement level is vital for a healthy society.

It is not hopeless. Some young Chinese, like 24-year-old government employee Felipe, are not planning on straying from the beaten path.

"I have discussed it with my family. We agreed that I will get married and have kids when I'm around 30," said Felipe, who is now single and says he's focusing on work.

"I think childless couples are rare. From what I can see, most people still want a traditional family," he said.

But he will have children only if circumstances allow it, Felipe said, referring to his and his partner's economic and employment situation.

When asked what if his future wife was to choose her career over childrearing, Felipe said he hoped things would work out.

"It's better to have kids. I don't mind if it has to wait," he said.

(Pseudonyms were used at the request of some of those interviewed.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3