Opinions

15:58, 25-Dec-2018

Opinion: Sea of changes as China considers revising Land Administration Law

Updated

15:16, 28-Dec-2018

Zhu Zheng

Editor's Note: Zhu Zheng is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law with China University of Political Science and Law. The article reflects the author's opinion and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The 2004 Land Administration Law (LAL) is reported to have been submitted to the National People's Congress Standing Committee for review and amendment. This is the third time the LAL will be revised since it was promulgated in 1986.

The amendment marks the first time that the so-called “presumption of state expropriation in non-agricultural use of rural collective land,” a practice that the state has kept for decades, is abandoned.

Article 43 of the LAL requires that non-collective parties can only use rural land for construction after it is expropriated and converted into state-owned land. That means, under the current laws, rural land must be state-owned before it can be used for non-agricultural purposes.

A farmer working in a rice field in the farming village of Gangzhong in China's eastern Zhejiang Province, November 19, 2013 /VCG Photo

A farmer working in a rice field in the farming village of Gangzhong in China's eastern Zhejiang Province, November 19, 2013 /VCG Photo

Article 9 of the 2007 Urban Real Estate Management Law (URML) echoes this logic and put it in a clearer way. According to the URML, “for a collectively-owned land within a designated urban area, it must be expropriated and turned into state-owned land first and then for leasing out to land users with due compensation.”

Put together, the laws tied up state expropriation with urbanization and de-agrarianization, i.e. when turning land legally designated for agricultural uses into land for non-agricultural purposes, state expropriation is necessary.

Setting aside the constitutional disputes surrounding state expropriation as a legal prerequisite for non-agricultural land construction, this article aims to outline the possible impacts of the revision and to provide an interpretation of the logic.

As for the possible implications, it is clear that the removal of expropriation steers clear of the normative boundaries for collective-owned land being used for non-agricultural purposes. In this sense, collective owners are allowed, if not encouraged, to lease out or transfer land for industrial and commercial uses, as long as the registration process is completed.

This at least ushers in two important changes. First, the amendment further curtails the powers of the local governments, as the scope of the land that can be taken is substantially limited to only six circumstances, say, infrastructure construction, public affairs, and large-scale buildings, where expropriations are permitted. As a result, the government's discretion to make compensation decisions are largely contained.

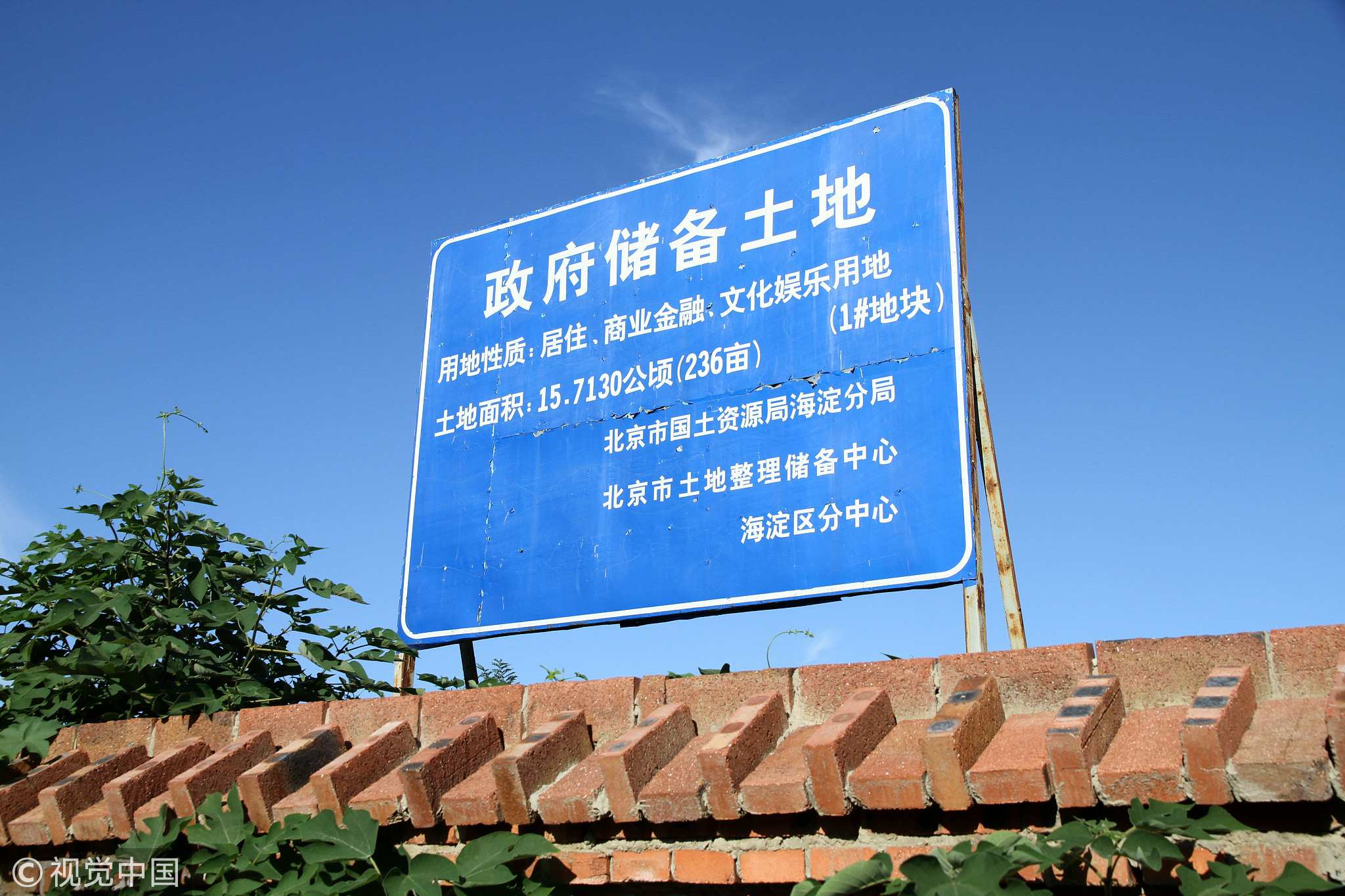

A sign reads the land is reserved for local government use in Beijing's Haidian District, China /VCG Photo

A sign reads the land is reserved for local government use in Beijing's Haidian District, China /VCG Photo

Under the old land regime, the statutory standard for compensation has been unfairly low, and it is very often up to the local governments to decide how much compensation is to be paid. Worse still, as little is said in the pertinent legislation, those whose land are taken are often excluded from the decision-making process in the first place. This has raised concerns of government corruption, and it is indeed a source for grievances and complaints in reality.

Second, the LAL amendment simplified the land transaction process and thereby gives impetus for private-owned land to be commercialized. This will alleviate the difficulties facing rural areas where increasing pieces of land will be better utilised in the future.

The logic of the amendments should be sorted out in the light of a much broader picture. As the economy is slowing down, land usage is to being prioritized in the overall economic agenda, and hopefully new stimuli would be identified to stabilize the market. More importantly, since the anti-graft drive is entering a new phase, government powers are to be more closely scrutinized and certain redundant process streamlined to stamp corruption out.

Although how the Constitution should be re-interpreted and what sub-primary legislation will be made are largely unknown at this stage, the revision of the land laws will for sure bring about a sea of changes.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3