China

15:45, 18-Jul-2018

Meet the people saving lives, one call at a time

Updated

15:38, 21-Jul-2018

CGTN

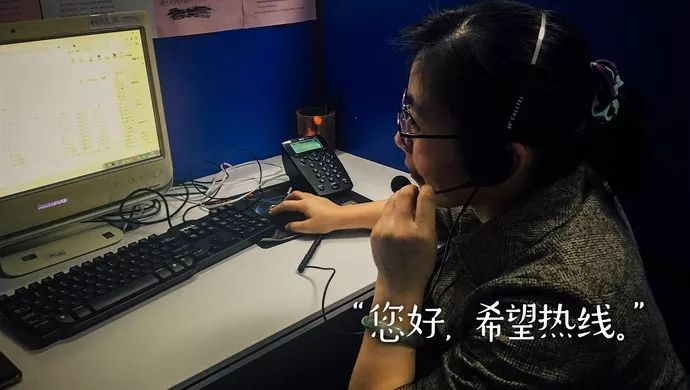

Inside a building in Shanghai, a group of telephone operators work 24/7 to prevent suicide by offering hope through Lifeline, a hotline created to help those who are on the edge.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 800,000 people commit suicide every year, which roughly equates to one life every 40 seconds.

Suicide is a global issue, but things have gotten worse in developing countries and lower-income areas. In China, suicide has become the fifth leading cause of death, accounting for one third of the globe's total suicides, as revealed in a study published in The Lancet medical journal.

To slow the growing problem, Lifeline centers have been placed across the country to intervene. Today, let’s meet the operators in Shanghai and listen to their stories.

Calls never stop, neither do the operators

“Hello, Lifeline,” Meng Xinyu said, as she put her dinner in the microwave.

A man was on the other side, sobbing.

“Are you crying?” Meng asked. “Would you take a deep breath? Do you feel better? Would you like to tell me what happened?”

“I want to go home,” he answered, while standing on a rooftop.

Photo via Ifeng.

Photo via Ifeng.

He then shared his struggles with being gay and unaccepted by his family. He was also treated unfairly in the workplace. He felt beaten by the world.

Forty-five minutes later, Meng hung up the phone after the man finally felt better and returned to her cold dinner.

Meanwhile, the phone rang again.

“The busy hour is from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. every day. I can hardly go to the restroom, or have meal,” Meng said, who volunteered to be a Lifeline operator six years ago while continuing her job at a state-owned company in Shanghai. Her shift is from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. every Tuesday.

Suicide signals

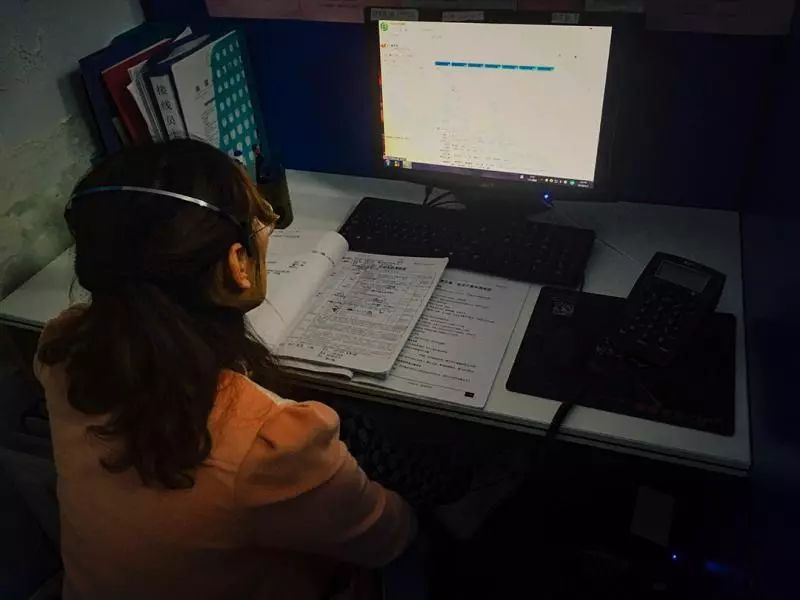

Another volunteer, screen named Fan Yanwen, is the only volunteer at the Shanghai location that is not from the city. She commutes one hour every week from Kunshan.

Photo via Ifeng

Photo via Ifeng

According to Fan, suicide signals are hiding in the words of the callers. It is crucial for operators to distinguish the emergency level of each call.

A less urgent call features people who blame others. They are usually still capable of describing the difficulties they are facing, which are overwhelming and make them question continuing their lives.

Calls where people blame others are the most urgent. The operator should be alert if the caller can't identify a specific incident or person to blame. It may be a signal that the caller has shifted from being upset to being numb.

There is a big gap between "I don’t want to live" and "I want to die." The latter has a high possibility of being followed by actions.

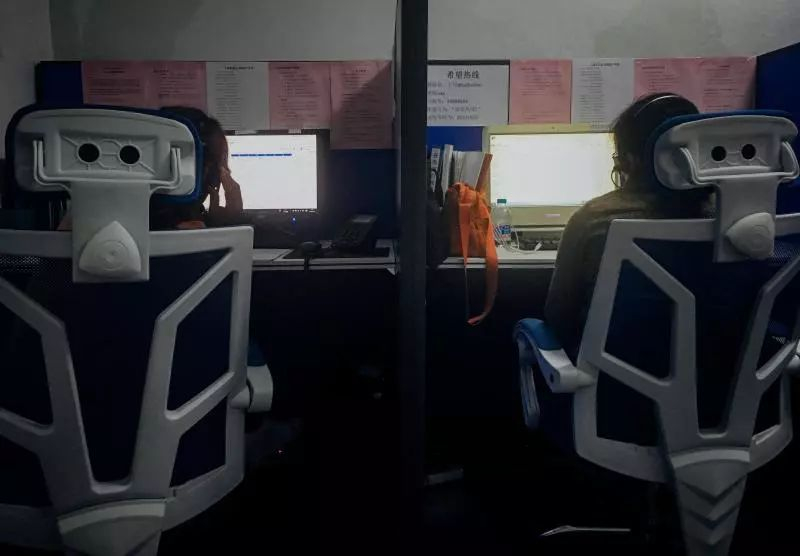

The task never ends. You will never know what the next call is about.

Photo via Ifeng.

Photo via Ifeng.

Lifeline, calling for hope

According to the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center, 93 percent of people committing suicide do not resort to the help of psychologists. And among the 2.8 million people who commit suicide in China every year, less than 1 percent have ever received a proper psychological evaluation.

Things may change as intervention is proving to be an effective way to prevent suicide, according to WHO.

By July 17, China had established 19 regional centers of Lifeline, and the total number of answered calls has reached 160,000 in the past six years. The calls transfer automatically to another station when all the local operators are busy, in the hopes of pulling back as many people as possible from the edge.

"Lifeline is similar to a lighthouse. On cold nights, its lights warm the hearts of people in need," Meng said. "We want to tell those facing difficulty that there is still someone in the world who cares and worries about them."

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3