Lifestyle

23:16, 22-Dec-2018

Paid period leave triggers Chinese debate over feasibility and equity

Updated

22:08, 25-Dec-2018

By Feng Yilei

03:31

China's eastern Shandong Province is set to give female workers who suffer from severe menstrual pain one or two days off every month on presentation of a doctor's certificate.

Many other provinces already have provision for menstrual leave as part of efforts to protect female workers.

Some even request that women on leave be fully paid, yet the implementation of this controversial policy is meeting resistance.

Some women describe menstrual pain as “a grinder inside,” with unbearable cramps, aches and fatigue all over the body. As China's period-care app Dayima reports, about four out of ten Chinese women struggle with pain during their menstrual cycle.

Miss Yang, as she would like to be known, is one of them. She said she usually rests at home on the first or first two days of menstruation.

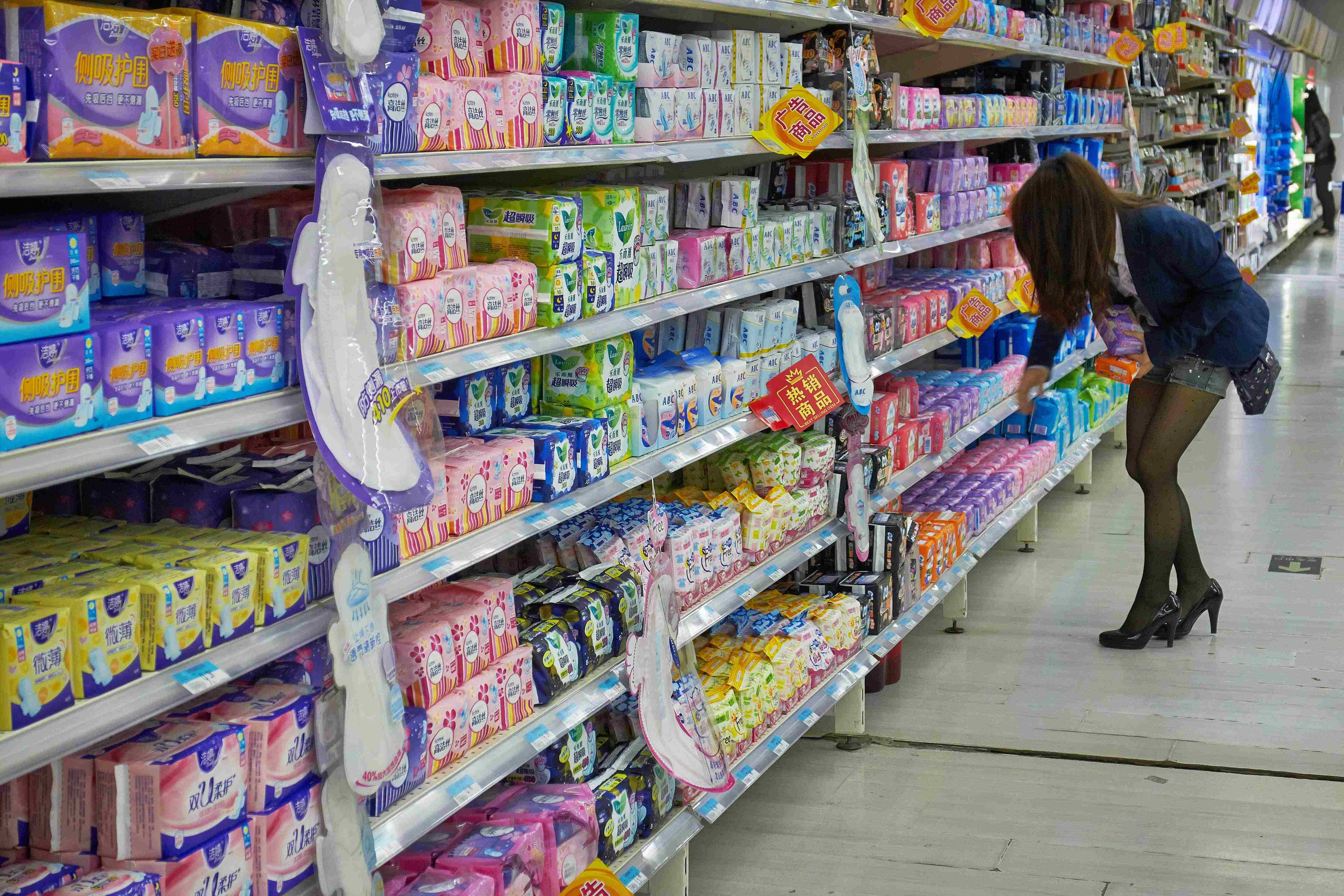

A woman picks up sanitary towels in a supermarket. /VCG Photo

A woman picks up sanitary towels in a supermarket. /VCG Photo

“Others cannot feel such pain," Yang said. "You are unable to work as your abdomen hurts whenever you move... It's uncontrollable and even painkillers cannot fully stop it.”

Although the paid leave policy has been in place for nearly two decades, most female employees in Beijing are still unaware or unwilling to take advantage of it.

A patient at Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital told us that among all the companies she had worked for, some allow her to take normal sick leave, whereas in some she uses her annual leave quota. After all, she said she felt bad having ask for leave every month. “Those who don't have this issue and cannot benefit from the policy may find it unfair. But if everyone takes the leave how can work be done,” she said.

It is also a big challenge for the doctors to tell whether the patient really needs days off. There are specific standards for doctors to rate the level of menstrual pain but it is still mainly based on patient description.

Li Hui, deputy director of physicians at the hospital's gynecology department, acknowledged that some patients might exaggerate their symptoms. But at least the doctors can control the number of days off, she said.

Li insisted that patients apply for a paid leave only during their period so that the situation could be diagnosed properly. But she also admitted that, in fact, only a handful of people come to her seeking a certificate for menstrual leave.

Female patients are seen at the Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital. /VCG Photo

Female patients are seen at the Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital. /VCG Photo

For women suffering from menstrual pain, getting medical diagnoses on requested days off means dragging themselves all the way to a hospital, waiting for hours and then having to convince a doctor. But even after they get the certificate, many worry that this entitlement comes at the cost of less pay, less authority, fewer opportunities and more stigma in the workplace.

Liu Bohong, a professor at China Women's University, pointed out that the regulation will actually raise the requirement for women and narrow their career options. Her reason is that employers will tend to use cheaper labor when some other labor costs more. And unlike maternity-leave allowance which is covered mostly by social insurance, where the funds for paid period leave come from remains a question.

A number of working women in countries like Japan, South Korea, Indonesia and India who are given similar legal rights also worry about being seen as weak. In other parts of the world, menstrual leave policies have emerged more on a company-by-company basis as staff welfare.

While supporters hail the rule for lifting the silence about women's necessary bodily functions, many like Liu believe a favorable environment for equal development instead of glorified segregation is what Chinese women really need.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3