Colombian voters will head to the polls Sunday for the first-round presidential vote. This is the first presidential election after the 2016 peace agreement between the incumbent President Juan Manuel Santos' administration and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Santos is not eligible for re-election, having already served two terms. The next president will only serve a single four-year term from August 7, 2018 to August 7, 2022, as presidential re-election was eliminated since 2015.

A worker assembles voting booths at a polling station in Cali, Colombia, May 25, 2018. /VCG Photo

A worker assembles voting booths at a polling station in Cali, Colombia, May 25, 2018. /VCG Photo

The president of Colombia is elected using the two-round system; if no candidate receives a majority of the vote in the first round, a run-off will be held between the top two candidates on June 17.

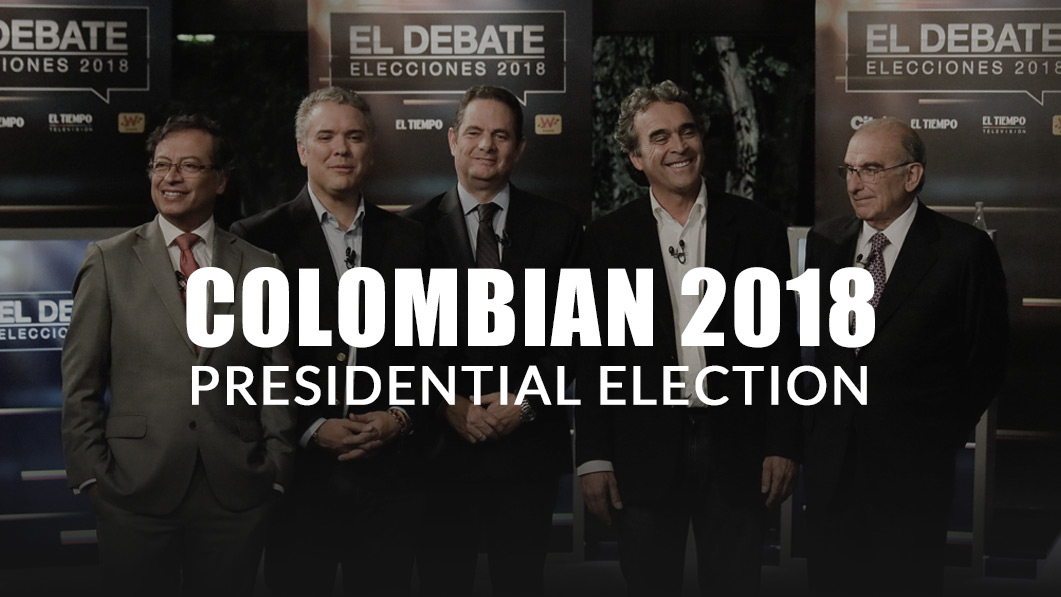

Who are the candidates?

In a race that began with eight official candidates on March 11, the number of candidates has been reduced to five.

The right-wing candidate is Ivan Duque, whose only political experience is as a one-term senator. However, endorsed by Alvaro Uribe, the most popular leader Colombia has had in decades, Duque has long been polling ahead of five other candidates with about 40% of the vote.

Gustavo Petro is running second with about 30% according to polls. He is leftist former guerrilla member and mayor of Bogota, gained support from millions of young people who are fed up with Colombia’s right-wing political status quo.

The middle options are Humberto de la Calle, German Vargas Lleras and Sergio Fajardo.

Fajardo, polling in the third place, is the former mayor of Medellin and governor of Antioquia, and seems to have successfully claimed the centrist mantle in public opinion.

Colombian former president (2002-2010) and current senator Alvaro Uribe (C), accompanied by presidential candidate Ivan Duque, who is planning to run for Uribe's Centro Democratico party, leaves after casting his vote at a polling station during parliamentary elections in Colombia, in Bogota, March 11, 2018. /VCG Photo

Colombian former president (2002-2010) and current senator Alvaro Uribe (C), accompanied by presidential candidate Ivan Duque, who is planning to run for Uribe's Centro Democratico party, leaves after casting his vote at a polling station during parliamentary elections in Colombia, in Bogota, March 11, 2018. /VCG Photo

Vargas Lleras was Santos’s vice president. He and Duque share similar professional backgrounds but Vargas Lleras is seen as playing traditional politics and lacks charisma.

De la Calle is the most experienced candidate who served as vice president before and also served as ambassador to Spain and the UK. Thus, he is the chief negotiator in Colombian peace process with the FARC.

Who may win?

The poll released May 3 by the Centro Nacional de Consultoria (CNC) for CM& news confirms a clear advantage by the 41-year-old Duque (38%) over the 58-year-old Petro (25%). They are followed by Fajardo (17%), Vargas Lleras (7%) and De La Calle (4%).

According to CNC, Duque widened the gap with Petro by four percentage points over a similar poll conducted two weeks earlier.

However, poll shows that Duque cannot reach 50% and may go to a second round with his closest running mate.

Colombia's presidential candidate for the Democratic Center Party, Ivan Duque, addresses supporters during his campaign closing rally in Bogota, Colombia, May 20, 2018. /VCG Photo

Colombia's presidential candidate for the Democratic Center Party, Ivan Duque, addresses supporters during his campaign closing rally in Bogota, Colombia, May 20, 2018. /VCG Photo

Experts listed two probably scenarios after May 27 as follows:

- Duque wins with a decisive lead with 35% to 40% of the vote but not enough to clinch victory on the first round. Petro comes in second place with 25%-30% of the vote. If the centrist independent candidate Fajardo is in third place, his percentages could split down the middle, benefiting both Duque and Petro, thereby narrowing the divide and making the run-off a cliff hanger.

- As Vargas Lleras’s center-right party has a very strong foothold in the departments that constitute Colombia’s coastal region, Vargas Lleras could deflate Petro and Fajardo on Sunday clinching second place. If Duque and Vargas Lleras come out on top on May 27, the hard left represented by Petro could retreat, and many of those voters would most likely abstain in the second round or cast a “voto en blanco” or protest vote, giving the upper hand to the winning candidate, as those votes will be added to the electoral threshold. Fajardo’s base once again splits down the middle, pushing Duque’s and Vargas Lleras’s points even higher.

Can the fragile peace deal hold?

At stake is whether Latin America’s fourth-largest economy will abandon the future of the peace deal with the FARC.

The peace deal, which ended the country's 52-year armed-conflict and won Santos a Nobel Peace Prize, saw thousands of guerrilla fighters hand over their weapons and join a reintegration process.

The bargain that underlies the peace deal is political participation in return for disarmament. The FARC then turned to the political party (Common Alternative Revolutionary Force) last September.

However, the political newcomer far failed to win much popular support.

In March's congressional elections, FARC won less than 1% of the vote and failed to pick up any additional seats outside the 10, which were guaranteed as part of the peace agreement.

A man casts his vote at a polling station in Cali, Valle del Cauca Department, during parliamentary elections in Colombia, March 11, 2018. /VCG Photo

A man casts his vote at a polling station in Cali, Valle del Cauca Department, during parliamentary elections in Colombia, March 11, 2018. /VCG Photo

The new party later also announced to quit from the presidential election.

There are plenty of critics who felt it was too soon for the former guerrilla fighters to be running for Congress and the FARC once had to suspend election campaign over threats to its candidates.

As frontrunner candidate, Duque pledged to rewrite the peace deal. Some even commented the Sunday's presidential election is a second referendum on the future of the peace process.

Duque supported the criticism that the deal lets demobilized rebels off the hook for serious war crimes.

Followers of the political party FARC, during the closing of their campaign before legislative elections in Fusagasuga, Colombia, March 3, 2018 /VCG Photo

Followers of the political party FARC, during the closing of their campaign before legislative elections in Fusagasuga, Colombia, March 3, 2018 /VCG Photo

"What we Colombians want is that those who have committed crimes against humanity be punished by proportional penalties, which is incompatible with political representation so that there is no impunity," he told reporters.

Petro supports the peace deal, as do Fajardo, De la Calle and Vargas Lleras.

In a survey conducted in April by Gallup, 70% of Colombians polled believe peace is now “on the wrong path,” and an even higher percentage (75%) are under the impression that the FARC will not abide to the commitments set out in the Final Accord.

Meanwhile, the arrest of FARC's former leader Seuxis Hernandez also threatens the fragile peace deal. He was arrested in April for plotting to traffic 10 tons of cocaine to the US.

Supporters of the rebel-group-turned-political-party FARC hold signs depicting former commander who had been slated to take a seat in Colombia's Congress Jesus Santrich, during a May Day march in Cali, Colombia, May 1, 2018. /VCG Photo

Supporters of the rebel-group-turned-political-party FARC hold signs depicting former commander who had been slated to take a seat in Colombia's Congress Jesus Santrich, during a May Day march in Cali, Colombia, May 1, 2018. /VCG Photo

If Colombia extradites Hernandez, as the US is calling for, it may violate the headline point of that agreement, which says crimes committed by the FARC before the deal was signed must be investigated by a special transitional justice tribunal (SPJ) – without the possibility of extradition.

The United Nations has urged caution on the Hernandez's case, saying the government’s actions will have “profound consequences for the peace process in Colombia.”

De la Calle, as the former chief peace negotiator, warned in April the country is “sleepwalking into war.”