Opinions

18:14, 27-Sep-2018

Opinion: Let poverty not be a penalty in wiping out tuberculosis

Updated

17:29, 30-Sep-2018

By Wang Xiaonan

Editor's note: The author is a journalist for CGTN Digital. The article reflects her views, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

China's first lady, Peng Liyuan, called in a video message Wednesday for an accelerated effort to bring an end to tuberculosis (TB) at the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). It was the first time TB -- the "perennial, pertinacious" epidemic that still wreaks havoc across much of the world -- was put on the UNGA agenda.

To many in the West, the word "tuberculosis" means just one vaccine among a bevy of shots they have to get some time in their lives. But around the world, the disease continues to kill at an alarming rate. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that deaths from TB in 2017 amounted to 1.3 million out of 10 million people infected.

Since German scientist Robert Koch first identified the bacterium responsible for TB over 130 years ago, what was a death sentence for much of history eventually became a chronic disease. Over the years, vaccines and antibiotics have proliferated to treat different manifestations of TB, which, however, remains the leading infectious disease killer in the modern world.

Robert Koch (1843-1910), German physician. Wood engraving published in 1884. /VCG Photo

Robert Koch (1843-1910), German physician. Wood engraving published in 1884. /VCG Photo

So there is little excuse when a preventable and treatable illness disproportionately affects those who can least afford it -- the poor.

The WHO reported that 97 percent of deaths from TB are in low- and middle-income countries. Estimates put about two-thirds of deaths in eight nations, including India, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, Indonesia, and South Africa. Meanwhile, Europe and the Americas account for only 6 and 3 percent, respectively.

That means there is still work to do. Impoverished regions and communities lack access to basic sanitation and healthcare facilities, so TB infects like wildfire amid inadequate medical services and ignorance.

According to the Stop TB Partnership, which works with the UN and other international bodies to eradicate the illness, inadequate health services hinder the diagnosis and treatment in such communities, while overcrowded and poorly ventilated home and work environments encourage the transmission of the disease.

A sleeping child photographed in March 2012 inside the pediatric department of Malakal Teaching Hospital which receives children suffering from conditions such as malaria, malnutrition, diarrhea and TB. /VCG Photo

A sleeping child photographed in March 2012 inside the pediatric department of Malakal Teaching Hospital which receives children suffering from conditions such as malaria, malnutrition, diarrhea and TB. /VCG Photo

In fact, TB's pervasiveness keeps the afflicted in poverty. Stop TB says that being sick results in missing three or four months of work, while burdening the fragile healthcare systems of developing countries. These factors and others result in an estimated 12 billion US dollars of lost income in the world's poorest communities.

Some who get TB might not even show symptoms. The WHO estimates that 1.7 billion people, or 23 percent of the world's population, have a latent TB infection, increasing their risk of developing an active version over the course of their lives. What's worse, in some societies, there is a social stigma to revealing that you have or once had TB as it is associated with being "unclean," so the disease can literally be a hidden killer, to both knowing and unwitting patients.

But there is hope. In November 2017, 75 ministers announced a landmark agreement to eliminate TB by the end of 2030 during a WHO conference in Moscow. And over the past few months, G20, BRICS and APEC -- among various regional organizations -- released communiques appealing for greater efforts against TB, especially drug-resistant strains.

The impetus carried over to the first-ever UN General Assembly meeting on eliminating TB on September 26, where Peng Liyuan -- wife of Chinese President Xi Jinping -- called for a fight to end the infectious disease. Over the years, Peng has relentlessly engaged in promoting TB prevention and treatment worldwide, especially since she was appointed WHO goodwill ambassador for tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in 2011.

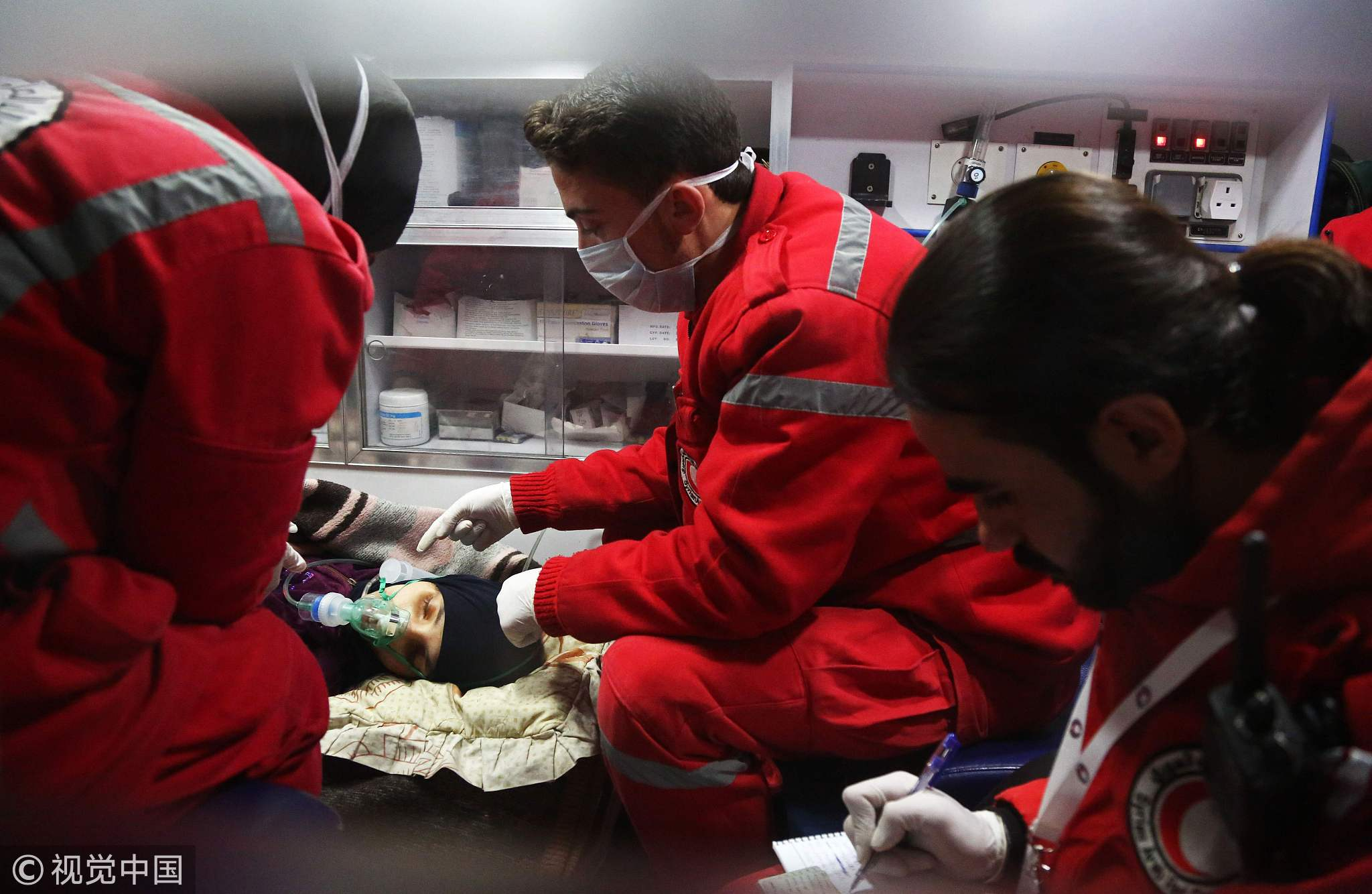

Volunteers from the Syrian Arab Red Crescent tend to a woman suffering from TB in an ambulance in Douma on the third night of evacuations from the besieged rebel enclave of eastern Ghouta on the outskirts of the capital Damascus on December 28, 2017. /VCG Photo

Volunteers from the Syrian Arab Red Crescent tend to a woman suffering from TB in an ambulance in Douma on the third night of evacuations from the besieged rebel enclave of eastern Ghouta on the outskirts of the capital Damascus on December 28, 2017. /VCG Photo

According to Peng, China has made remarkable progress in TB prevention and treatment thanks to the effort by the Chinese government and around 700,000 volunteers.

In China, the epidemic has seen declining incidence and fatality over the past years, despite relatively high prevalence, with students and migrant workers part of the susceptible population.

Last year, the TB incidence rate and mortality rate among Chinese stood at 60.5 and 2.3 per 100,000 people respectively, according to the National Health Commission. The incidence rate fell by over 14 percent from 2012, at an annual drop of 3 percent. This is faster than the global average.

The progress can be attributed to China's heavy investment in tackling the contagious disease. Authorities from the country's health commission's disease control division stated that government funding increased to 640 million yuan in 2017 from 260 million yuan in 2004 -- almost threefold.

The successes of this large developing country can serve as a guide for poorer nations that still have a high prevalence of TB. Government policies, partnerships with health authorities and organizations, investment in healthcare, and encouraging local health initiatives are all essential in educating and treating communities that lack the resources of wealthy nations.

The United Nations building in New York City. /VCG Photo

The United Nations building in New York City. /VCG Photo

Money is flowing into the fight against TB, but not enough. Funding for the 119 low- and middle-income countries reached 6.9 billion US dollars this year, according to the WHO, but the Stop TB Partnership's plan to eradicate TB by 2020 estimates that 10.4 billion dollars is needed in 2018 to reach the goal.

As the world moves forward on all fronts, economic progress shouldn't only mean that poor communities aspire to higher living standards, but should also imply universal access to good healthcare services and greater awareness of sanitary conditions. Only then can we all share in the wealth generated by the engine of globalization.

(Cover photo: Peng Liyuan speaks during a ceremony in Geneva, Switzerland, January 18, 2017. /Xinhua Photo)

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3