Editor's note: Tom Fowdy is a British political and international relations analyst and a graduate of Durham and Oxford universities. He writes on topics pertaining to China, the DPRK, Britain, and the U.S. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Recent news have reported an increase of fighting and violence in Libya, North Africa, as rival factions contending to be the country's legitimate government drag out a prolonged conflict.

Leading the military, General Khalifa Haftar has vowed on an assault on Tripoli, the country's capital city and seat of the administration backed by members of the United Nations Security Council. Western nations have called for the fighting to stop, accusing the marshal of launching an illegitimate and undemocratic coup.

One might note of course, that Libya's problems aren't new or even surprising.

Instead, they are all an extension of a catastrophic foreign policy decision made at the beginning of this decade, which is to have violently overthrown Muammar Gaddafi and to have plunged the country into a crisis it has not recovered from.

Failing to comprehend the country's fragile politics and society in empirical ways, the aftermath of the 2011 intervention has ensured that violence, chaos, extremism and untethered destruction have become a mark of everyday life in the Maghreb nation. If anything, a cold reminder that imposing "democracy" by the hand of external force never pays off.

Local militiamen, belonging to a group opposed to Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar, stand next to vehicles the group said they seized from Haftar's forces at one of their bases in the coastal town of Zawiya, west of Tripoli, April 5, 2019. /VCG Photo.

Local militiamen, belonging to a group opposed to Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar, stand next to vehicles the group said they seized from Haftar's forces at one of their bases in the coastal town of Zawiya, west of Tripoli, April 5, 2019. /VCG Photo.

In Western countries, the notion of democracy is often taken for granted, to the point that it is perceived and thus treated in highly idealistic ways.

Whilst in practice, popular rule is made possible through a stable set of socio-economic conditions, entrenched institutional norms and thus a legitimized and widespread accepted set of "narratives" which permits the regime to exist unchallenged. Western political thought with its emphasis on universal moral truths often assumes that the choice between authoritarianism and democracy are a simple question of "good person" vs. "bad person," rather than the underlying political, social and economic currents which drive the conditions of governance.

Therefore, with the west in turn assuming a holistic mandate to preach its values to others, as is the historical legacy of Christianity, all that is truly needed to be done to create a functioning democracy is to simply overthrow and depose the bad people, and thus like in any typical Western film or work of fiction, all will be well.

This was certainly some of the logic utilized in the NATO-led effort to depose the regime of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 and the ill-fated attempt to build a democracy that followed after.

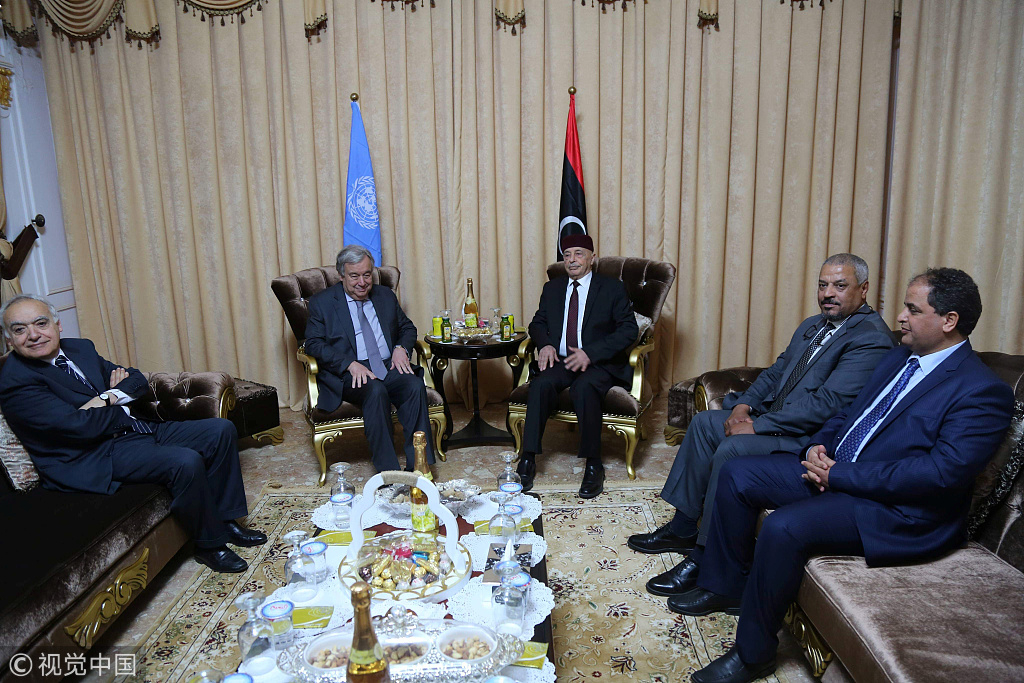

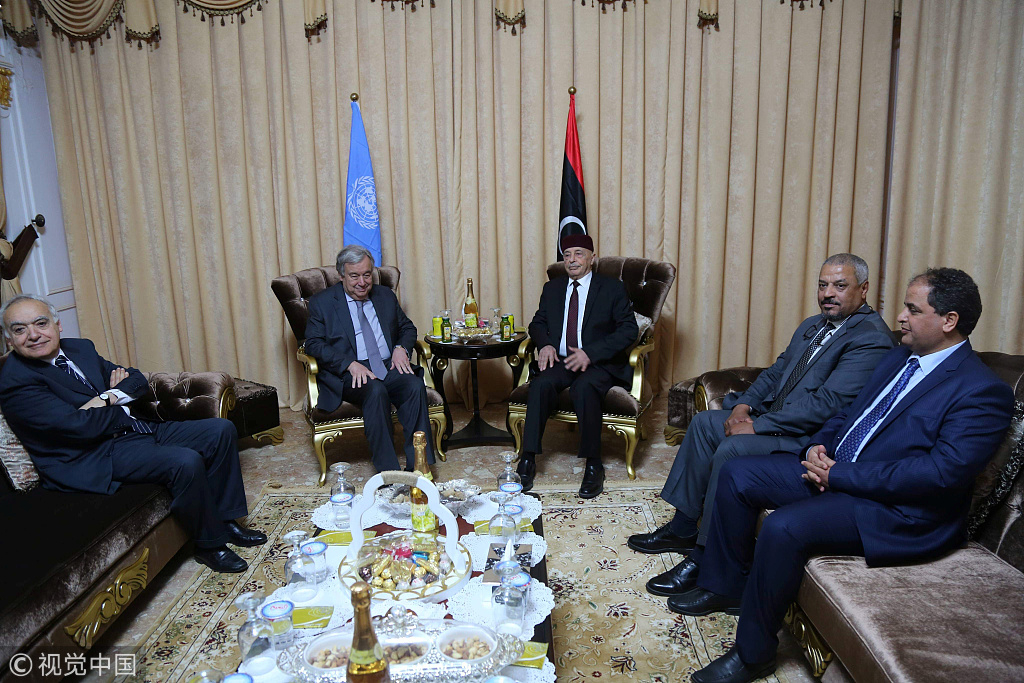

Aguila Saleh, Libya's parliament president, meets with Secretary General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres in Tobruk, Libya, April 5, 2019. /VCG Photo.

Aguila Saleh, Libya's parliament president, meets with Secretary General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres in Tobruk, Libya, April 5, 2019. /VCG Photo.

For obvious reasons, the Gaddafi regime was not popular amongst the international community and faced widespread disapproval for its sponsoring of terrorist acts and insurgent groups in western countries, efforts at nuclear proliferation and rampant corruption.

The fact, however, that he was seated on Europe's periphery made the fate of the regime a core national interest to several countries in the region, thus when the regime plunged into civil war in 2011 between Gaddafi and the National Transitional Council, decisive action needed to be taken. But the wrong choices were made.

Rather than seeking to simply contain the conflict and prevent civilian casualties, as they claimed they were going to do, the participating NATO coalition instead, believing they could easily build a harmonious and free country from scratch, decided to overstretch their mandate and advocate a full-blown regime change turning the war in favor of the rebels, which would climax in the brutal murder of Gaddafi in the open streets.

Behind it all was the belief that by getting rid of the "bad man," a new democracy could be built and of course, with the holistic view of how democratic systems operate, such a regime could only be prosperous and stable. It was all a risk worth taking.

Khalifa Haftar (2nd, L-R), the military commander who dominates eastern Libya, Aguila Saleh Issa, president of the eastern Libyan House of Representatives, and Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj during an international conference on Libya at the Elysee Palace in Paris, France, May 29, 2018. /VCG Photo.

Khalifa Haftar (2nd, L-R), the military commander who dominates eastern Libya, Aguila Saleh Issa, president of the eastern Libyan House of Representatives, and Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj during an international conference on Libya at the Elysee Palace in Paris, France, May 29, 2018. /VCG Photo.

But this did not coincide with reality. As noted above, Western-style societies were not generated by simple moralistic forces or the preaching of values, not least in a country like Libya. Its domestic political scene is complicated. It is a fragile state, created from colonial imposed boundaries, which contains a number of fragmented tribal and ethnic-based loyalties and a weak, inorganic political center; the Gaddafi regime operated by keeping these social faultlines loyal to the center through a mixture of force, ideology and a patronage system through the distribution of oil revenues.

Whilst it lasted 42 years and made Libya wealthier than any country in Africa, it was ultimately a failed state. In the midst of the Arab Spring, the tensions would eventually spill over into the conflict which premeditated his downfall, but to remove it by force was a mistake.

Which is why of course, after his demise, the fabled democracy promised by the West did not materialize. Instead, the existing social tensions and legitimate central authority simply combusted into more war, as well as the rise of extremist ideologies, all of which further destabilized the country and posed catastrophic consequences for Europe, including the spread of terrorism, migration crises and so on.

It is thus only inevitable that Libya's political paradigm has now given birth to a new "strongman" leader who is seizing the country by force.

This is the legacy of Libya. Western-imposed military interventions are often based on a faulty idealism which takes for granted the privileges of home and fails to understand that democracy does not operate in a vacuum and is not a simplified game of good vs. evil.

The escalation of the conflict in Libya into a full-blown regime change in 2011 stands out as one of the most catastrophic miscalculations in modern Western foreign policy, one which has overseen the complete destruction, disarray and decimation of the North African nation, without any merits to show for it whatsoever.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)