Culture

18:34, 02-May-2019

From Renaissance genius to Ninja turtle: 500 years of da Vinci

By Sim Sim Wissgott

Did Leonardo da Vinci already design computers and robots?

His name is synonymous with genius. Far ahead of his time, he designed flying machines, tanks and robots, churned out visionary concepts in anatomy, astronomy and even music, and painted arguably the most famous painting in the world: the "Mona Lisa."

Even today, he is a household name, inspiring movies, novels and even cartoon characters.

On the 500th anniversary of his death, here is a look at Leonardo da Vinci's lasting legacy and fame.

Renaissance man

A scientist, an inventor, a mathematician, an architect, a sculptor, a painter and much more, da Vinci – born in 1452 – was the very definition of a polymath or "Renaissance man."

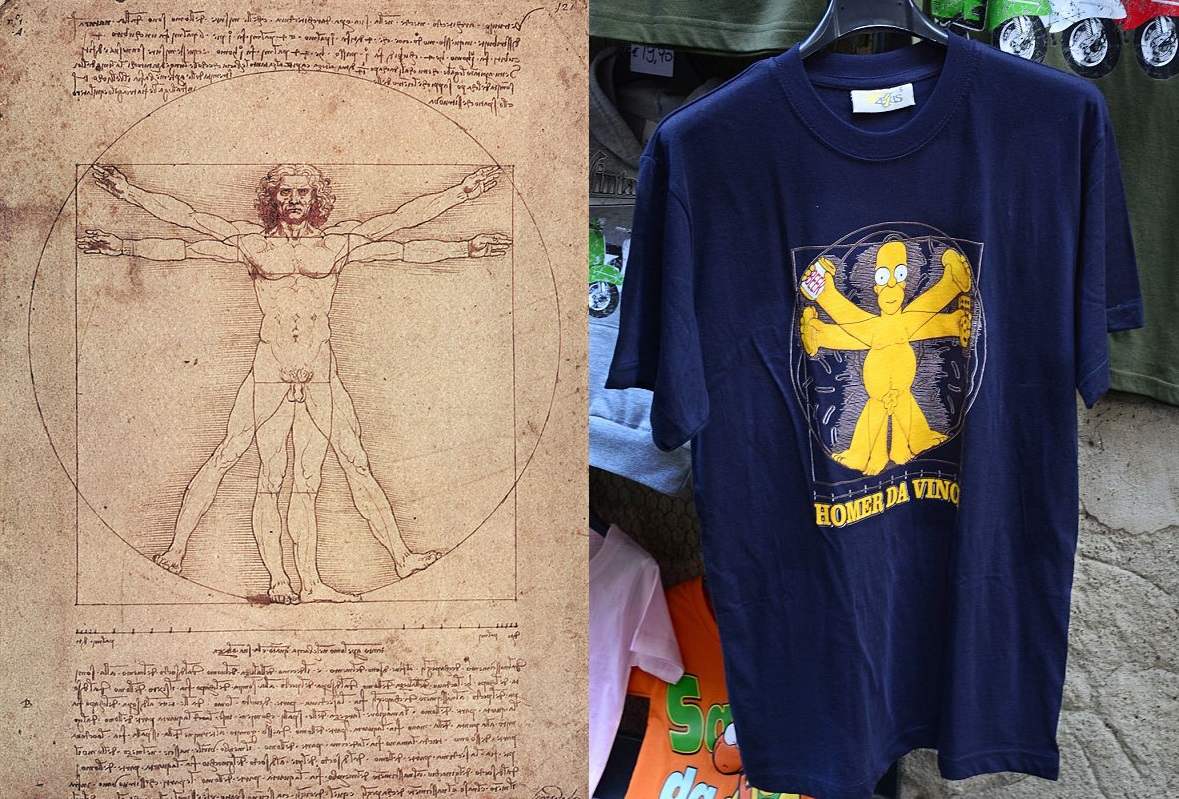

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (L) and a T-shirt depicting cartoon character Homer Simpson in the same pose at a souvenir shop in San Gimignano, Italy. /CGTN composite of Getty Images pictures

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (L) and a T-shirt depicting cartoon character Homer Simpson in the same pose at a souvenir shop in San Gimignano, Italy. /CGTN composite of Getty Images pictures

The mysterious smile of "Mona Lisa" still captivates tourists and art historians alike. His "Vitruvian Man," demonstrating the proportions of the human body, is probably the world's most famous drawing, featured in countless ads and internet memes.

For most of the last 500 years, da Vinci's fame – already acquired during his lifetime – was based on his art.

He is credited with developing the concepts of chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and dark) and sfumato (fading between colors to soften lines) and for his use of perspective.

But his interests extended far beyond oil paints and brushes to everything from engineering and geometry to botany and physics, as seen in the piles of manuscripts he left behind, filled with writings and sketches.

Leonardo, the inventor

Long before the age of laptop computers and mobile phones, da Vinci came up with designs for machines that would not be seen for several more centuries.

Most of these ideas were not realized during his lifetime, or would never work in their original form. But they reveal a mind that was light years ahead of his contemporaries.

A working model of Leonardo da Vinci's self-propelled cart is seen on display at the Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy, April 23, 2004. /Getty Images

A working model of Leonardo da Vinci's self-propelled cart is seen on display at the Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy, April 23, 2004. /Getty Images

Among da Vinci's most famous inventions was a mechanical knight that could sit, stand and move its head independently, thanks to a system of pulleys and gears – a 15th-century precursor of the robot.

He also designed an armored vehicle that strongly resembled a modern-day tank, while drawings discovered in the 1960s seem to have been for a mechanical calculating machine.

His viola organista, combining the characteristics of a keyboard and a string instrument, never really caught on.

But he may have presaged one of the hottest innovations of the 21st century: the driverless car. Five centuries before Tesla and others started looking into self-driving vehicles, da Vinci developed a three-wheeled cart that could travel 40 meters on its own thanks to a wind-up system, and whose steering could be pre-programmed.

Defying gravity

One of da Vinci's biggest obsessions was flying. An entire manuscript, the Codex on the Flight of Birds, was dedicated to how birds fly, the laws of gravity and how this could be adapted to make flying machines.

A model of Leonardo da Vinci's flying machine on display at the Museo Leonardiano in Vinci, Italy. /Getty Images)

A model of Leonardo da Vinci's flying machine on display at the Museo Leonardiano in Vinci, Italy. /Getty Images)

At a time when engines were still nowhere near being invented and commercial air travel was not even a dream, he made designs for a parachute and a flying machine with wings that flapped like a bat, and came up with an "aerial screw" that was an early ancestor of the helicopter, with circular sails instead of rotors.

Da Vinci also tried to defy the laws of physics closer to the ground, sketching a contraption that would allow him to walk on water.

Leonardo, the scientist

But he also had a more practical side.

A skilled anatomist, he drew detailed drawings of the muscles in the human body, the blood vessels, the bones and the internal organs – even dissecting hearts and dead bodies to better understand how they worked. Unpublished for centuries, these sketches are now considered among the world's best studies of the human body.

He also observed the skies and explained the concept of earthshine – the fact that we can discern the whole moon at night even when only a thin crescent is lit up.

Da Vinci, 500 years on

A darling of nobles and aristocrats – his patrons included Cesare Borgia, Pope Leo X and France's King Francis I – da Vinci's reputation was already well established before his death in France at age 67.

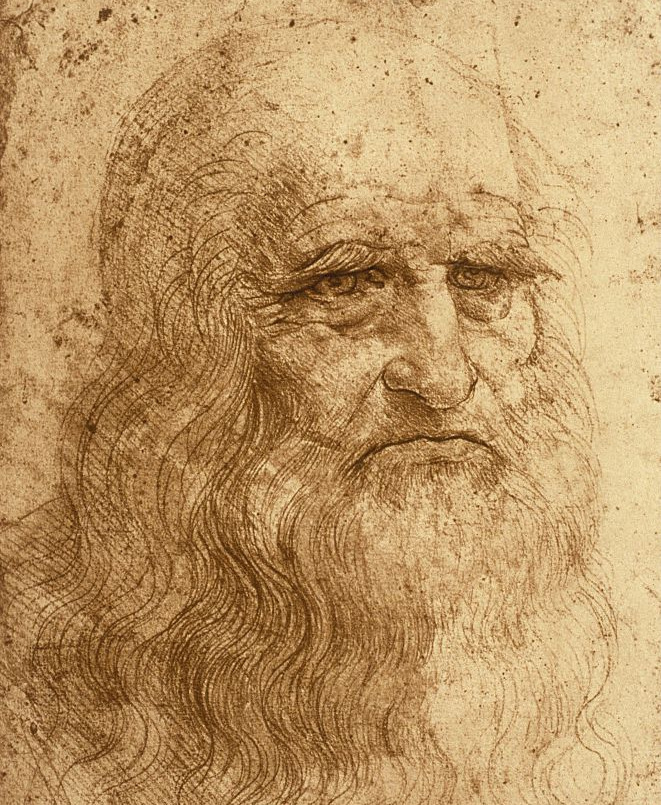

Leonardo da Vinci self-portrait around 1512. /Getty Images

Leonardo da Vinci self-portrait around 1512. /Getty Images

Today, his continuing popularity can be seen in the regular attempts – by museums, researchers and YouTube vloggers – to recreate and test his inventions.

Artists like Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol produced modern versions of his "Mona Lisa" and "The Last Supper." The latter inspired the best-selling novel "The Da Vinci Code."

Beyond his work, Leonardo himself remains a superstar, with cameos in Hollywood movies, TV series like "Star Trek" and "Family Guy", and the video game "Assassin's Creed."

Alongside his Renaissance colleagues Michelangelo, Donatello and Raphael, he even lent his name to one of the pizza-munching title characters in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic books.

For a man who died half a millennium ago, da Vinci remains as fresh and trendy as ever.

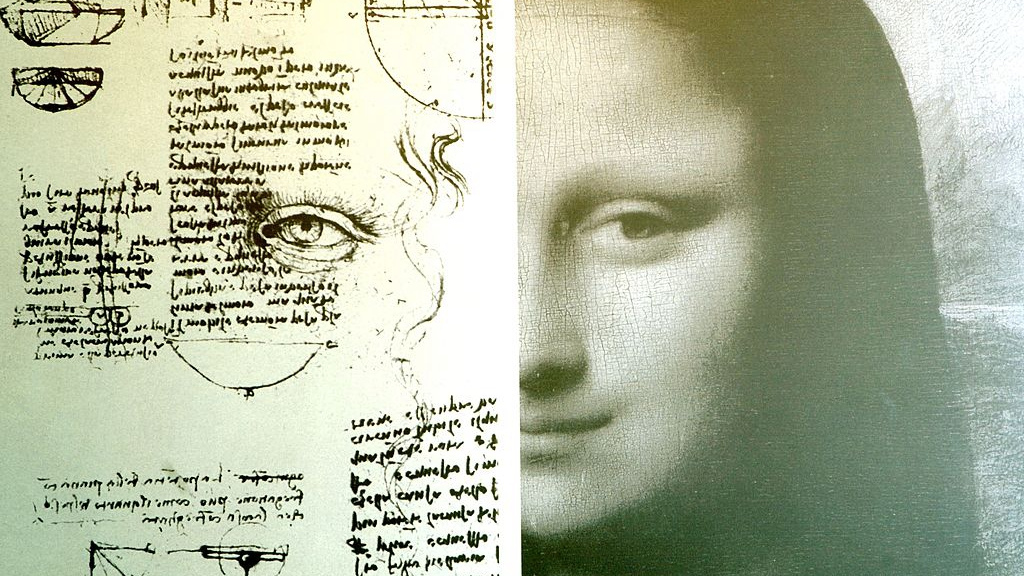

(Cover picture: A study for Mona Lisa's eyes at the Leonardo Da Vinci exhibition vernissage at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy, March 27, 2006. /Getty Images)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3