Opinion

22:35, 04-Mar-2019

Meng Wanzhou case: the goose is not cooked yet

Zhu Zheng

Editor's note: Zhu Zheng is an assistant professor focusing on constitutional law and politics at China University of Political Science and Law. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On March 3, Huawei's Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou sued Canadian authorities for breaching her constitutional rights during her house arrest in Vancouver. According to the report, she is now “seeking damages for misfeasance in public office and false imprisonment.”

The new complaint was lodged after Canada approved the extradition proceedings against Meng on Friday. In late January, the U.S. justice department charged Meng and Huawei with conspiring to violate U.S. sanctions on Iran.

Canada's approval of extradition proceedings marked the formal start of the high-profile process, and the suit filed by Meng's defense team with the B.C. Supreme Court further stoked the fire. For sure, both sides will exchange fire in a fiercer way, and her lawyer's tactics will be most likely employed as ammunition for the next stage of the fight.

For these reasons, it is more appropriate to set aside political and diplomatic rows and focus on the underlying legal issues that currently remain unexplored but would become a bone of contention in the following trials.

On the whole, it should be admitted that Meng Wanzhou case is fraught with thorny legal problems, and both international and domestic laws will have to be considered if Meng were to be extradited to the U.S.

Huawei finance chief Meng Wanzhou. /VCG Photo

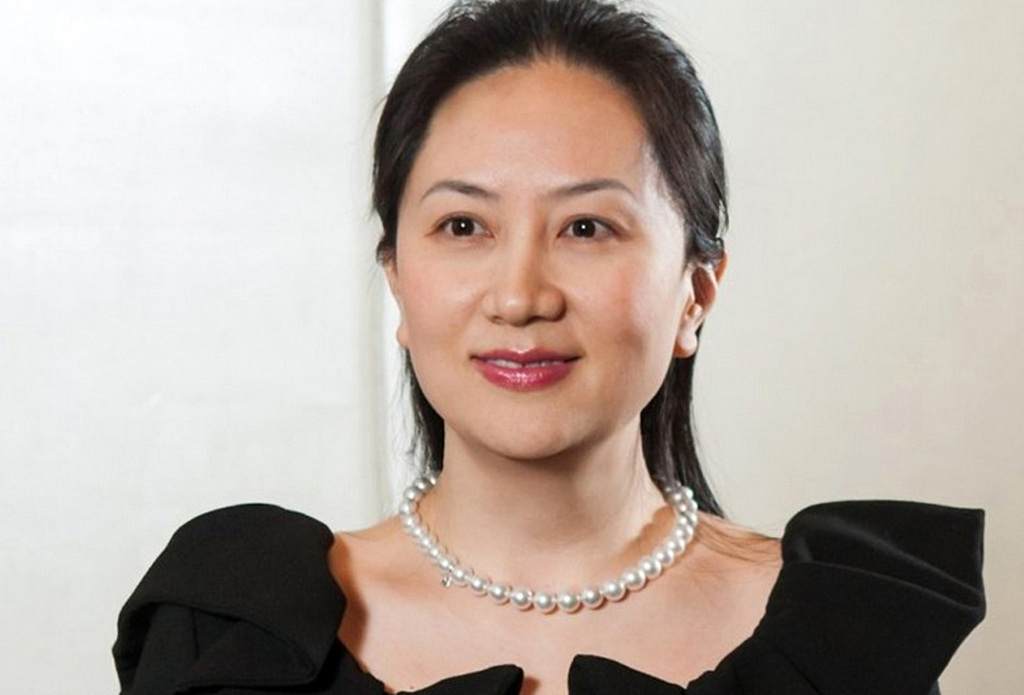

Huawei finance chief Meng Wanzhou. /VCG Photo

In terms of international laws, the long-standing U.S.-Canada treaty lays down certain steps for the extradition to go through, it stipulates that the request will have to be tabled by the U.S. Department of Justice, and the offense for which extradition is sought should be a crime in both America and Canada.

Domestically, Canadian Crown prosecutors argued that Meng violated section 380 of Canada's criminal code, which pertains to the charges against Meng with lying to banks about Huawei owning a subsidiary Skycom that conducted business with Iran. Since bank fraud is illegal in both Canada and the U.S., Canadian officers issued an authority to proceed.

In the imminent extradition hearing, a date of which will be set in court on March 6, a Canadian judge will determine if the evidence offered by the U.S. side describes conduct that, had it occurred in Canada, would have justified a trial in Canada.

However, it should be aware that the hearing itself is not a trial – Meng will face a trial in the United States if she is extradited by Canada. But will the extradition be carried through very soon?

Not likely, at least for the moment. Because of the aforementioned civil claim filed by Meng on Monday, the extradition process will be delayed, with more divergence inside the Canadian administration exposed and multiple decisions to be appealed.

Therefore, it is clever for Meng's defense team to submit a new claim, which will not only further prolong Canada's already slow-paced justice system, but also undermine the entire process of extradition, and even tarnish the reputation of the Canadian authorities if the constitutional violation is eventually verified.

Statistics showed that from the 2007/08 to 2017/18 fiscal years, Canada arrested 755 individuals for extradition, and ultimately extradited 681 of them. Therefore, when it comes to extradition, there is a joke that “once you are sought for extradition, your goose is pretty much cooked.”

But as a consequence of the complicated legal and political implications of the case, as well as Meng's lawyer's tactics and the loopholes of the Canadian extradition system, it might take years before the dust settles. In this sense, the goose is not cooked yet and will possibly get away.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3