Europe

15:36, 15-Feb-2019

May's Brexit defeat: Not meaningful, not meaningless

By John Goodrich

Theresa May's government was again defeated in the British parliament on Thursday night, but in the strange world of Brexit things are rarely simple.

The ballot wasn't "meaningful" – the term given to binding votes – and so makes no legal difference to how May proceeds in her efforts to take Britain out of the European Union.

But the political consequences make the 303 to 258 loss, after a debate in which the prime minister played no part, anything but meaningless.

Read more:

May's Conservative Party came together in January – a rare show of unity – to vote for a vaguely worded amendment that called for her to return to the EU and seek changes to the Irish backstop arrangement.

On Thursday, that temporary truce between the right of the party and the government was broken.

The European Research Group, the faction of hardline Brexit supporters in the Conservative Party, abstained because the motion they were voting on appeared to rule out a no-deal exit – an outcome that many of its members are thought to prefer.

And while the loss does not bind the prime minister's hands, it does send a clear message to the EU negotiators: There's no guarantee that May has a majority for the changes she is asking them for, and that in turn makes it less likely they will grant awkward concessions.

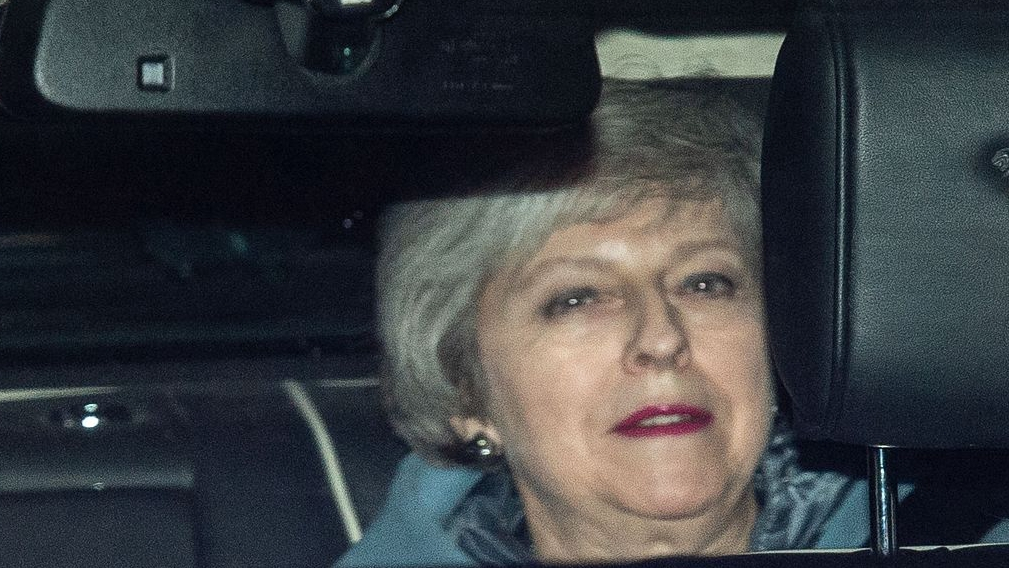

British Prime Minister Theresa May is driven from the Houses of Parliament in London after losing a Brexit vote, February 14, 2019. /VCG Photo

British Prime Minister Theresa May is driven from the Houses of Parliament in London after losing a Brexit vote, February 14, 2019. /VCG Photo

Senior Conservatives such as former foreign secretary Boris Johnson and former Brexit secretary Dominic Raab were among those to abstain, citing concerns that the motion they were asked to vote for ruled out a no-deal, and five of the party's MPs voted against.

May has repeatedly said Britain will leave the EU on March 29 and a no-deal is still on the table, but when the "Brady amendment" was passed by Conservatives MPs in January a second amendment calling for no-deal to be ruled out was also approved by a cross-party majority.

The motion put to MPs on Thursday appeared to ask for endorsement of both amendments, although not explicitly.

Why the government chose to use this language is unclear. It's now much more difficult for May to argue she can deliver the "substantial and sustainable majority," promised just two weeks ago, when she does eventually hold a "meaningful" vote.

High profile EU figures have repeatedly complained in recent days that there have been no concrete proposals from Britain, and the government has now been defeated on Brexit 11 times in 14 months, according to calculations by The Times.

People's Vote supporters at the Blindfold Brexit protest ahead of a crunch debate in the House of Commons in London, UK, February 14, 2019. /VCG Photo

People's Vote supporters at the Blindfold Brexit protest ahead of a crunch debate in the House of Commons in London, UK, February 14, 2019. /VCG Photo

Notably, on Thursday key amendments on a second referendum or giving parliament power to rule out a no-deal were not voted on, and that sets up the next debate and vote on February 27 as a potentially decisive moment.

It remains unclear whether the late February vote will be "meaningful" or advisory, but backers of a cross-party compromise and ruling out no-deal are likely to be emboldened by Thursday's loss.

Several members of the government have suggested they would resign to vote against a no-deal unless the option is taken off the table soon, and that could lead to the prime minister acting preemptively over the next two weeks, possibly by confirming a delayed exit date.

That in turn would infuriate the European Research Group, whose members on Thursday showed they're in no mood to follow the party line. There are no easy choices for May, and but over the next two weeks she could be forced to pick a side.

Thursday's vote made concessions from the EU – which has repeatedly ruled out reopening the withdrawal agreement – even less likely, and takes Britain further away from leaving with a deal, on schedule.

It wasn't a "meaningful" vote, but it is likely to prove consequential.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3