Opinions

16:00, 01-Dec-2018

Opinion: USMCA's goal of isolating China may fail

Updated

15:27, 04-Dec-2018

Ken Moak

Editor's note: Ken Moak taught economic theory, public policy and globalization at the university level for 33 years. He co-authored a book titled "China's Economic Rise and Its Global Impact" in 2015. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The leaders of the U.S., Canada and Mexico just signed the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement or USMCA at the G20 Summit in Argentina on November 30, promising a "new era" in bilateral or trilateral trade agreements.

The USMCA replaces the North America Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, which U.S. President Donald Trump claimed was "unfair" to the United States. One reason was that it denied American dairy products into the Canadian market, accusing the latter's supply management policy of keeping the supply of industrial milk less than demand as "unfair" subsidy. The president was also not "happy" with the trade dispute mechanism, allowing an independent penal to settle conflicts.

The main features of the USMCA include: increasing local content on automatics from 62.5 percent to 75 percent; Mexican wages to be no less than 16 U.S. dollars per hour; Canada allowing U.S. dairy farmers to have four percent of the market.

And perhaps the most important involves Article 32 which requires a trade partner to give the others a three-month notice before negotiating a trade agreement with a "non-market" economy, vaguely defined as any country that a partner "determines" to be in violation of its free-market policies. The informed partner will have six months to decide whether to withdraw from the USMCA.

Article 32 was meant to prevent Canada and/or Mexico from negotiating a trade agreement with China. Raising the Mexican minimum manufacturing wage was to bring manufacturing jobs back to U.S. soil, the major aim of Mr. Trump's "America First" policy. The four-percent access to the Canadian dairy market was probably meant to placard U.S. farmers who have been complaining about the northern neighbor's protectionist policy.

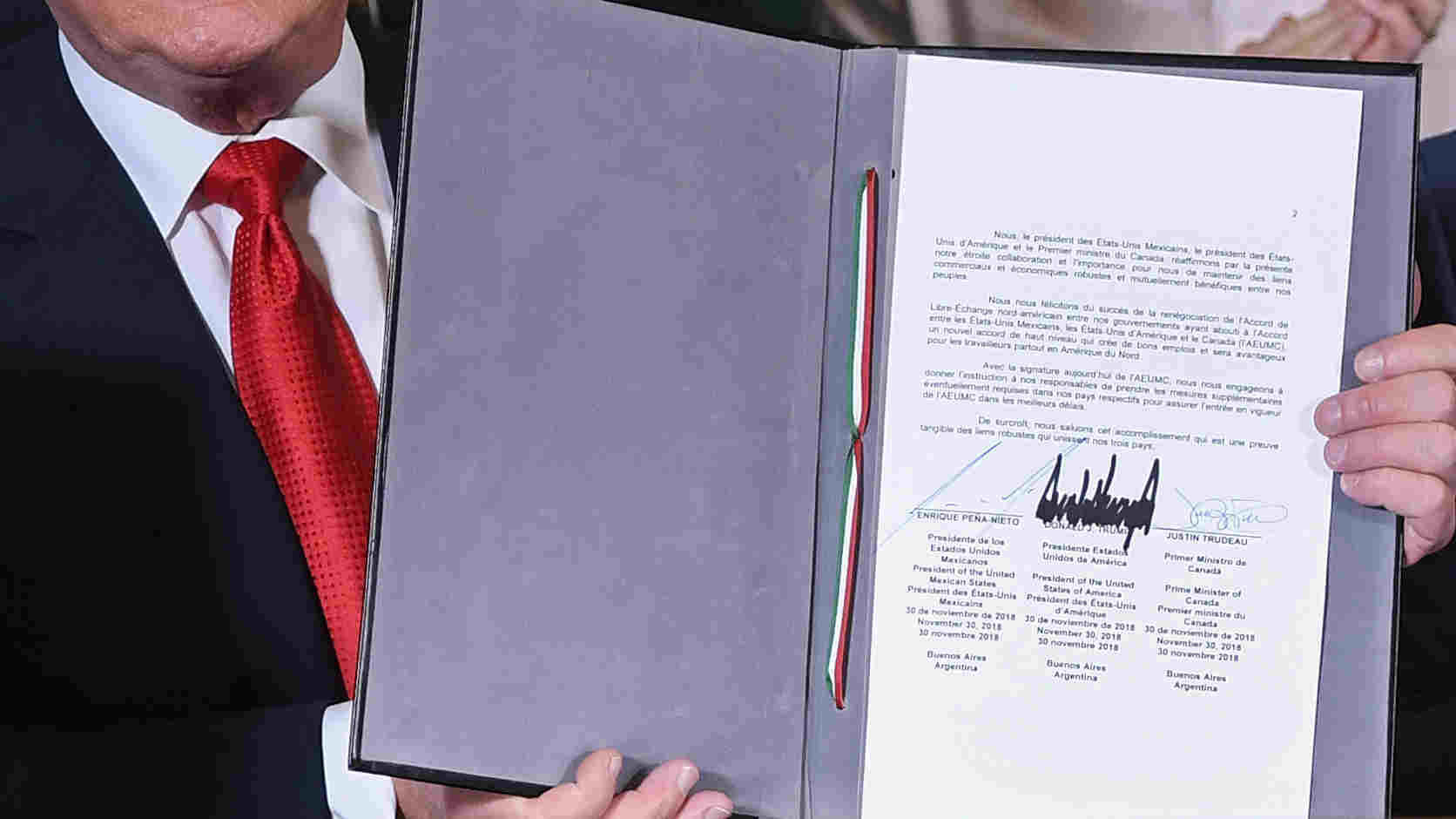

Mexico's President Enrique Pena Nieto (L), U.S. President Donald Trump (C) and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sign a new free trade agreement in Buenos Aires, on November 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

Mexico's President Enrique Pena Nieto (L), U.S. President Donald Trump (C) and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sign a new free trade agreement in Buenos Aires, on November 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

Whether the new agreement is better than the one it replaced is unclear. For example, farmers in Canada and U.S. have reservations about the dairy access provision. Canadian carmakers accused Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of selling them.

Further, neither Canada nor Mexico conceded on giving up Article 19 which allowed all trade disputes to be settled by an independent trade dispute mechanism. The U.S. originally demanded the disputes be settled in an American court of law.

The USMCA will likely be ratified

Canada and Mexico argue that the USMCA will not deter them from negotiating a trade agreement with China. Indeed, China and Canada had just concluded a meeting in November of this year to explore the way in forging free trade and bilateral investment agreements.

However, the reality is that the Canadian and Mexican economies are highly dependent on that of the United States with bilateral trade estimated at over 581 billion U.S. dollars and 557 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 respectively, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In this sense, defying the U.S. demand of not negotiating a free agreement with China is easier said than done.

Further, there is a strong anti-China constituency in Canada. Over 80 percent of Canadians oppose Chinese state-owned enterprise investment in Canada and an equal percentage is wary of Chinese investment in the Alberta oil sands.

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a news conference ahead of the signing of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) at the G20 Leaders' Summit in Buenos Aires, on November 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a news conference ahead of the signing of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) at the G20 Leaders' Summit in Buenos Aires, on November 30, 2018. /VCG Photo

For the reasons indicated above, the USMCA's in replacing the NAFTA is a foregone conclusion. The U.S. Congress is already showing signs of fast tracking its ratification. The legislatures of Canada and Mexico may debate the content, but would likely ratify the agreement because of economic reality. Trade between the three countries would unlikely be any different from that under the NAFTA framework.

However, as indicated earlier, all three countries would gain very little from the USMCA. It could, therefore, be argued that its real purpose might be to isolate China from the world trade and investment systems.

Can the USMCA isolate China?

Since Donald Trump ascended to the U.S. presidency, his sight was on China, claiming China has been "eating America's lunch" with "unfair" trade practices, including currency manipulation, state subsidies, technology theft, forced technology transfer and other misdeeds. His main support for the accusations was the huge trade deficit with China, estimated at over 375 billion U.S. dollars in 2017.

Whether he will succeed in doing so is not clear. China has ways to deal with the trade war. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) coupled with its huge domestic market could be another potential market for cooperation. Also, the Chinese government has enough fiscal and monetary policy tools to remedy any damages the trade war would cause.

Being the biggest trade partner to over 120 countries, China cannot be easily isolated. The opposite might be true in that more and more countries are joining or interested in joining China's BRI. The recent China International Import Expo held in Shanghai in which 58 billion U.S. dollars of business deals were signed is another indication that the world is embracing China.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3