British scientists reported that they have discovered tiny tubes and filaments in some Canadian rock believed to be the oldest known fossils, shedding new light on the origins of life.

In the new study, published in Nature journal, Mattew S.Dodd, Dominic Papineau and their colleagues at University College London examined rock found along the eastern shore of Hudson Bay in northern Quebec, Canada.

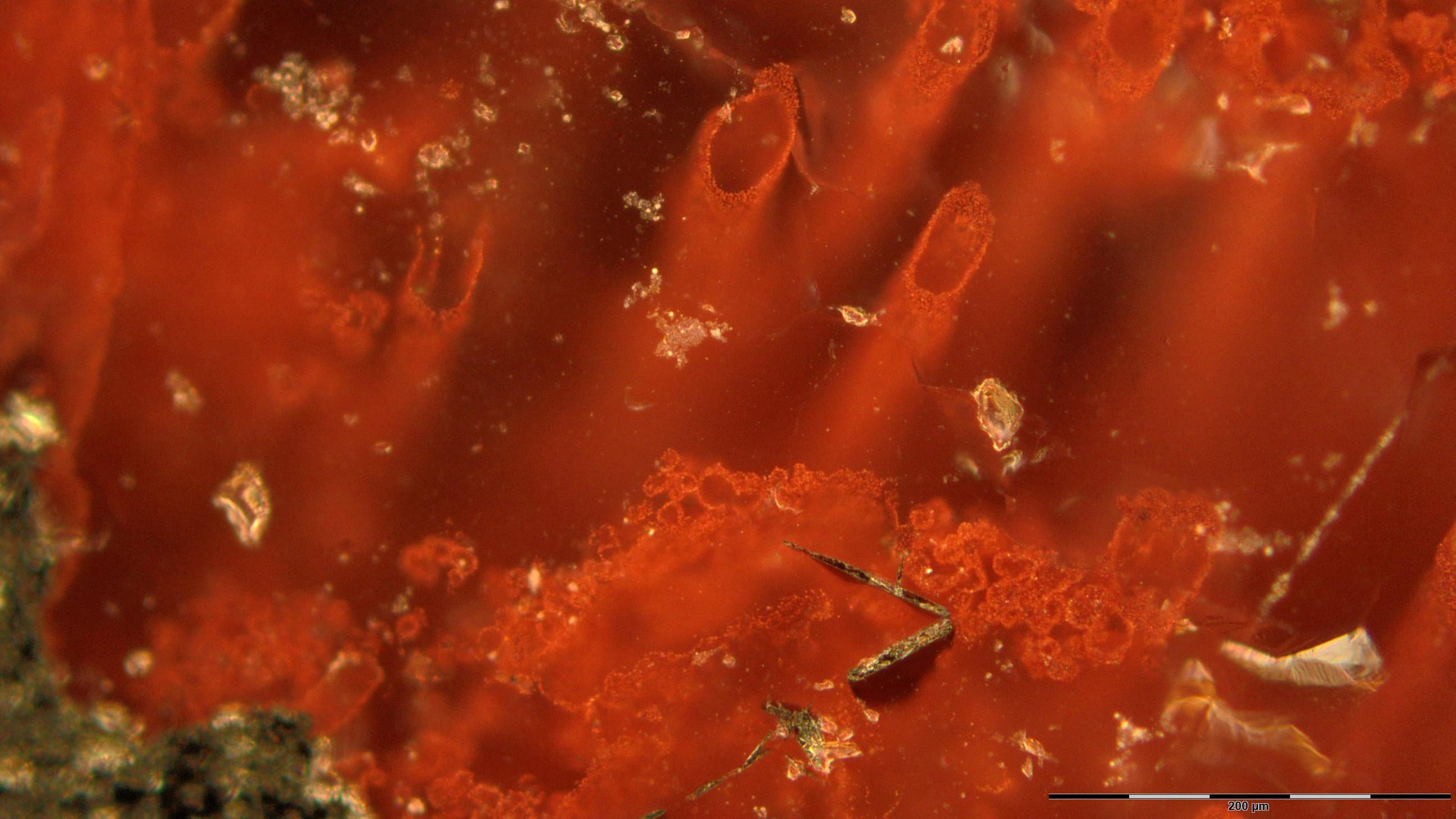

The fossil structures were encased in quartz layers in the so-called Nuvvuagittuq Supracrustal Belt (NSB), a chunk of ancient ocean floor, containing some of the oldest volcanic and sedimentary rocks known to science.

Haematite tubes from the NSB hydrothermal vent deposits in Quebec, Canada. /Reuters Photo

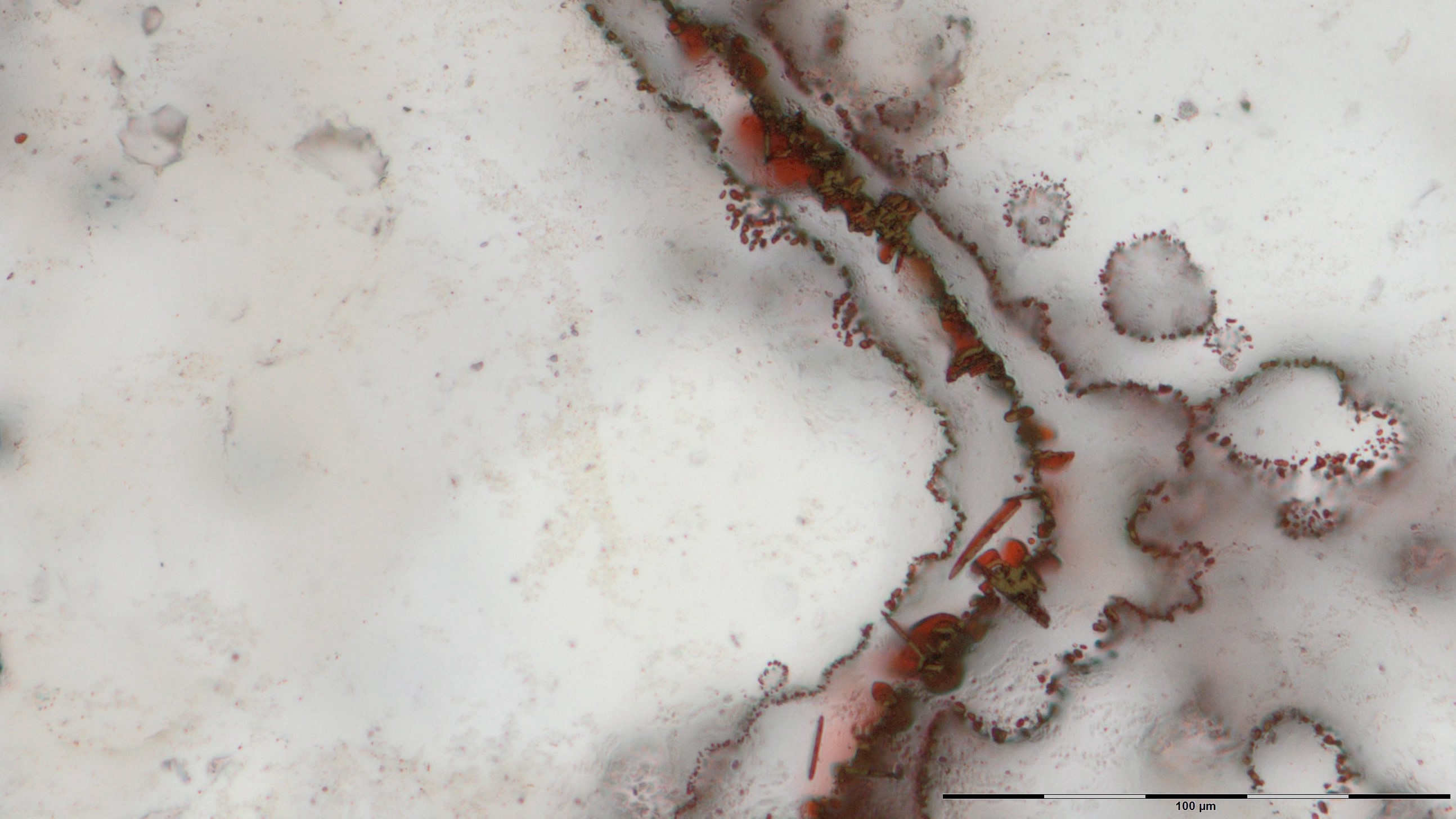

Comprised of tiny tubes and filaments made of an iron oxide known as haematite, the microfossils are believed to be the remains of bacteria that once thrived underwater around hydrothermal vents, relying on chemical reactions involving iron for their energy.

Today, such vents are known to be important habitats for microbes. And Papineau thinks this kind of setting was very probably also the cradle for life forms between 3.77 and 4.28 billion years ago (the upper and lower age estimates for the NSB rocks) — just 340 million years after the formation of the planet.

That would surpass the proposed 3.7 billion-year-old fossil evidence found in Greenland last August.

There is now solid evidence of life dating back about 3.5 billion years. Earth was a billion years old by then, and scientists have long wondered if even older fossils might be found.

A haematite filament enveloped by a fine irregular layer of nanoscopic haematite from vent deposits in the NSB in Quebec, Canada. /Reuters Photo

Such a discovery could have big implications for the understanding of life’s early evolution.

The discovery of the structures, the authors add, also highlights intriguing avenues for research to discover whether life existed elsewhere in the solar system, including Jupiter’s moon, Europa, and Mars, which once boasted oceans.

As with all such claims about ancient life, the study is contentious. The key question is always whether the rock features were really produced by living things.

Martin J. Van Kranendonk, a geologist at the University of New South Wales, called the patterns in the rocks “dubiofossils” — fossil-like structures, perhaps, but without clear proof that they started out as something alive.

Abigail Allwood, a NASA geologist, said the authors have produced "one of the most detailed cases yet made" for evidence of life in rocks older than 3.5 billion years. But "it's an extraordinary claim to make and you do need extraordinary evidence," she said to AP.

“I think the authors have done a good job,” David Wacey said to The New York Times, who researches the origins and evolution of life at the University of Western Australia. He was not surprised that the new work had drawn criticism. “It may be many years before a consensus is reached,” he said. “But this is how science progresses.”

9032km