By CGTN’s Tao Yuan

The missing teacher

One day’s drive on rocky terrain only gets us as far as the foot of the mountain. The rest of the way was too dangerous to attempt by car.

We walked for another three hours with a local guide on a snow-covered mountain in mud so thick, it caked our shoes, making the climb all the more difficult.

We were trying to reach an elementary school in a village hidden deep in the mountains. Such schools are not uncommon here, but their remoteness means few people know they even exist.

We are in Liangshan, a prefecture in southwest China’s Sichuan Province, and one of the country's poorest regions. The area is populated predominantly by the ethnic Yi group, who have their own unique language and culture and are relatively isolated from the outside world.

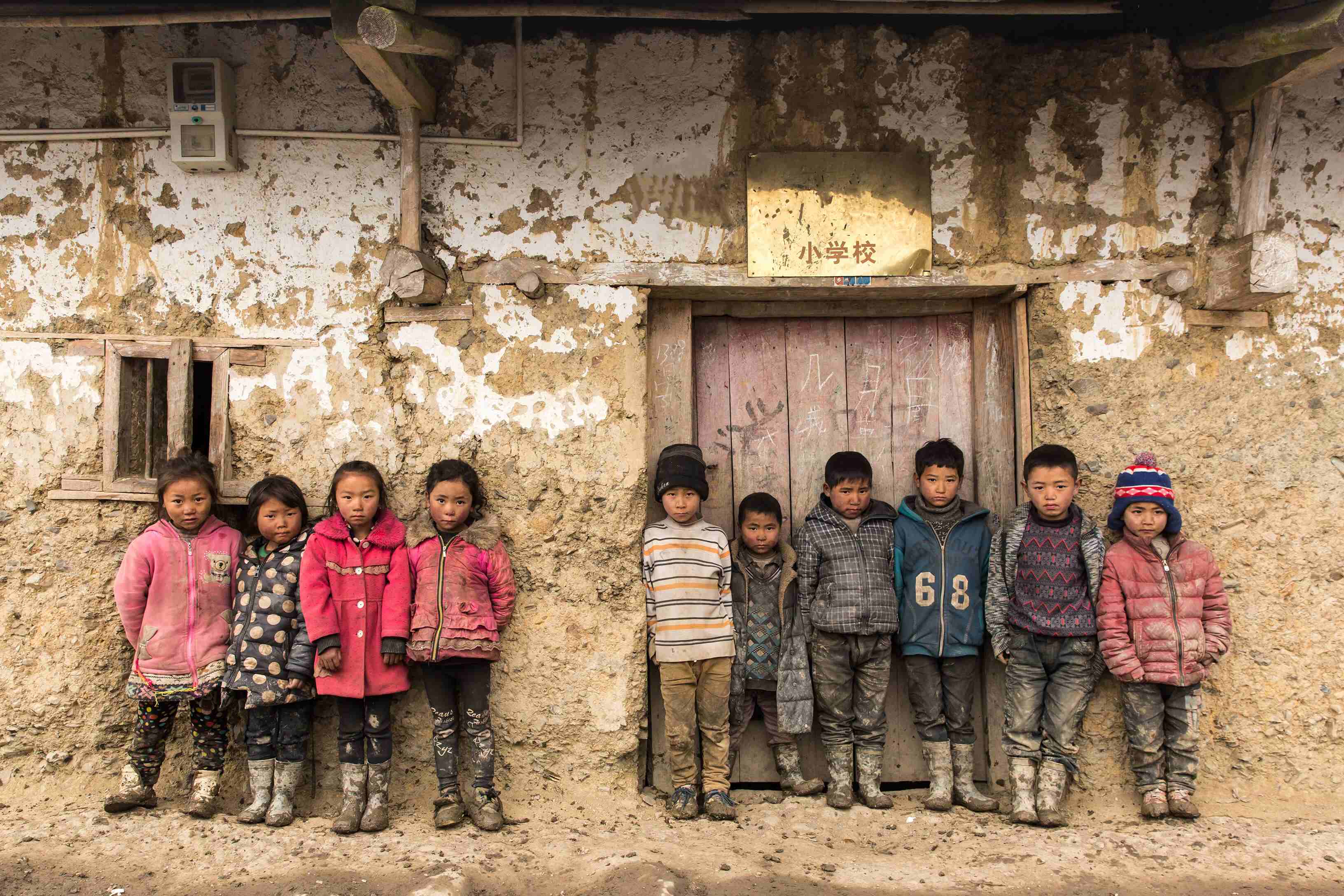

Children in village in Liangshan on their first day of school / CGTN Photo

We had hoped to speak to a rural teacher who has been working here for 12 years. There was no way to reach him in advance due to the poor cellphone coverage of the area, but we had heard he’s unusually outspoken about the difficulties for China’s rural children to access decent education.

Ultimately, the interview didn’t happen.

Our guide told us the local publicity department had been tipped off of our arrival, and had warned the teacher not to talk to us.

We are not certain if that’s what actually happened, and if it is, why the publicity department would be so suspicious of us. But the level of poverty in this region is shocking. Houses here are built from sun-dried mud bricks. In front of them, women sit picking lice from each other’s hair. A few school-aged girls are running around, their faces and hands covered in dirt, their skin dried into wrinkles.

This was supposed to be their first day of school, but they didn’t have a teacher other than the one we had planned to speak to.

China's rural children

Our guide, 20-year-old local Zhang Ershi, quit school after finishing third grade.

“Our teacher didn’t think so highly of us,” he said in broken Mandarin that took some getting used to. “So I decided, why bother?”

Zhang Ershi quit school after completing 3rd grade / CGTN Photo

Ershi’s story is shared by many children in rural China. A study published last year which involved the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Stanford University, and several Chinese universities, found that around 63% of all children in China’s villages dropped out of school before 12th grade. That’s almost two out of every three of China's rural children.

The final straw for Ershi was when he saw a classmate drown while crossing a river on his way to school. That’s when he decided he’d had enough.

The harsh mountainous terrain in the region means children here often have to make long, perilous journeys to and from school. So-called “cliff villages” attracted widespread attention after the state-run Beijing News published a series of striking photos of schoolchildren as young as six climbing vine ladders up sheer cliff faces.

Children of Liangshan climb “sky ladders” to school. / CGTN Photo

Ershi now spends three to four months a year working as a construction laborer in a northern city. The rest of the year, he returns home to occasionally help with farm work. But mostly, he just idles around town. His 17-year-old sister has worked in a restaurant in Dongguan for more than a year.

“I miss her so much,” says Ershi, “The first time she called, I cried.”

Addressing poverty alleviation through education

Motivated by rising public concern, the Chinese government has decided to take a stronger response.

During this year’s political season, President Xi Jinping said that it was heart-wrenching to think of the children in Liangshan while talking with delegates from Sichuan Province.

The Education Ministry says improving the quality of education in rural and poverty-stricken areas is among the country’s key tasks.

“Education should be on the forefront of China’s poverty alleviation efforts,” said Pan Chengying, a member of the country’s top law-making body, the National People’s Congress.

She has founded two bilingual kindergartens in her hometown of Ganluo, a poverty-stricken county in Liangshan.

The visual contrast of the modern facility, and its harsh mountain surroundings is striking, and raises hopes for the future of education in the region.

Modern kindergarten founded by NPC deputy Pan Chengying in poverty-stricken Ganluo County. / CGTN Photo

The Mandarin poem

Back in the village, where we climbed a mountain to get reach, we spent an afternoon with the children. We mainly communicated with laughter and handshakes, as they only spoke the language of the Yi people. But they were eager to show us the few Mandarin poems that their teacher had taught them.

One goes like this: “My chair in front, my chair behind, my chair is my best friend, my chair follows me around, just like my little black dog.”

1867km