Business

15:45, 04-Mar-2017

One year on – Evaluating Premier Li’s 2016 work report: Economy

Updated

10:55, 28-Jun-2018

Almost one year has passed since Premier Li Keqiang delivered his third annual work report to delegates at the opening of the fourth plenary session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) in Beijing.

The buzzword of last year’s report was “jingji” (economy in English) - it was mentioned 90 times.

The report pointed out the challenges that lie ahead and outlined guidance for overcoming such problems. As Li told the NPC, China at the start of 2016 was suffering from overcapacity in heavy industries, amid growing “downward pressure on the economy.”

Premier Li Keqiang delivered the annual government work report at the opening of the fourth plenary session of the National People’s Congress in Beijing on March 5, 2016./Xinhua Photo

Premier Li Keqiang delivered the annual government work report at the opening of the fourth plenary session of the National People’s Congress in Beijing on March 5, 2016./Xinhua Photo

So one year on, what measures did the central government put into practice, and how effective have they been?

GDP growth target of 6.5-7%

Premier Li told legislators that the economy was facing difficulties as a result of structural reform, against the backdrop of a sluggish global economy. These problems will last for a period of time, the premier added, as he outlined an achievable GDP growth target between 6.5 and 7 percent.

In early 2017, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said China’s 2016 GDP growth met the expectations outlined by Premier Li, reaching 6.7 percent for the year. Despite being the slowest growth in 26 years, the head of the NBS Ning Jizhe promised the figures were authentic and reliable.

Strong fiscal support, loose monetary policy, and a booming property market in the first three quarters of last year were the main factors that drove the growth. Chinese banks extended a record 1.8 trillion US dollars in loans in the past year, as the government used more credit-fueled stimulus to meet its growth target.

Overcapacity

Overcapacity was another factor cited by Li as playing a role in the economic slowdown. Since 2010, heavy industries such as steel, coal and cement have shown signs of overcapacity and low productivity, with many state-owned enterprises (SOEs) contributing to a glut of construction supplies.

As international and domestic demand for construction materials has dropped off, factories have been left with excess supply. This has produced a drag on growth, as heavy industrial firms struggle to sell their goods, placing a financial and political burden on the central government.

Premier Li told legislators that cutting overcapacity would be one of the eight top economic goals of 2016, and that the central government would spend 100 billion yuan over the next two or three years to help local governments deal with laying off workers.

Overcapacity cuts come as part of China’s ongoing supply-side reforms, as the country looks to guide its country into a “new normal.” Transitioning from an investment-led economy to a services-based model, the government is giving wide support to innovation and entrepreneurship across the country.

So how have the capacity cuts worked out so far?

Workers demolished a steel factory in Liupanshui city, Guizhou Province in November, 2016. /VCG Photo

Workers demolished a steel factory in Liupanshui city, Guizhou Province in November, 2016. /VCG Photo

In January 2017, China’s top economic decision-making body, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), said the country had cut 45 million tons of steel and 250 million tons of coal by the end of November 2016, fulfilling government targets ahead of schedule.

Xu Shaoshi, the head of the NDRC, said cutting excess production will remain a priority in 2017, as the country aims to cut another 45 million tons of annual steel capacity.

Despite initial success in cutting capacity, there have been stumbling blocks. In one case, the State Council in November announced investigations into illegal expansion in the coal and steel sectors in Hebei and Jiangsu provinces.

Cutting overcapacity in 2017 is unlikely to get any easier. He Fan, chief economist with the Chongyang Finance Institution of Renmin University, said that most of the annual capacity that was cut in 2016 had already been idle, without giving further details.

Cutting overcapacity will be crucial over the next few years, and plays a big role in the Chinese government’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020), which sets out to establish a settled economic growth rate of around 6.5 percent, while doubling 2010 GDP and household income levels by 2020.

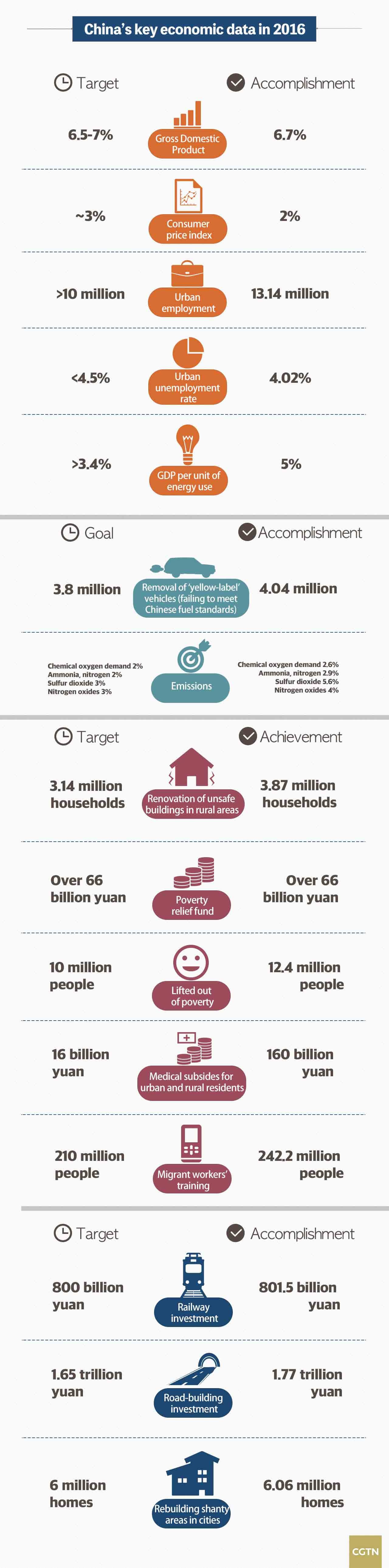

China's key economic data in 2016.

China's key economic data in 2016.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3