New species of shipworm discovered feeding on chemicals found in human flatulence

2017-04-18 15:00 GMT+8

Editor

Xie Zhenqi

US scientists have recently found a rare species of giant shipworms in the mud of a shallow lagoon in the Philippines. Although its existence had been known about for centuries, no living example has ever been spotted and documented in scientific journals.

About three-to-five feet long and two inches wide, the mud-dwelling creature looks like the entrails of a black alien from a horror film.

A researcher examining the shipworm. / University of Utah Photo

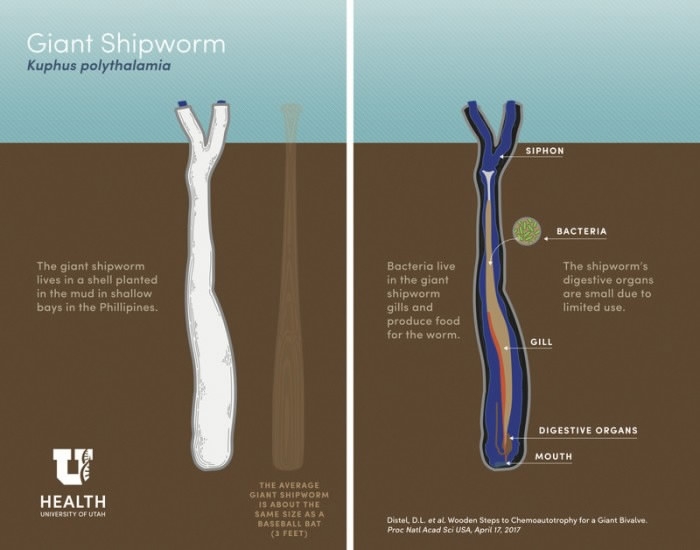

This species, which is technically a type of saltwater clam, is the longest among bivalve mollusks recorded and has a formal name Kuphus polythalamia.

Professor Marvin Altamia and her team from University of Utah first discovered the shipworm, in an international joint effort with colleagues from Northeastern University, University of the Philippines, Sultan Kudarat State University and Drexel University.

Margo Haygood, University of Utah Health Sciences, discusses the giant shipworm shells with Rande Dechavez and Julie Albano of Sultan Kudarat State University.

A scientist removes the top of a shipworm shell to reveal the living animal inside. / University of Utah Photo

“It’s sort of the unicorn of mollusks,” Margo Haygood, a marine microbiologist at the University of Utah and also a researcher from the team, told reporters.

The researchers showed in a documentary how its shell surfaced near a gulf in the Philippines. They also unearthed five samples from the region and published a study in journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on Monday.

The shipworm is encased in a tusk-like shell, which sparked curiosity among researchers about how they eat.

Graphic illustration in the study. / PNAS Photo

They speculated that, in contrast to ordinary shipworms, this species sources energy from hydrogen sulfide, commonly found in rotten eggs and human flatulence.

They were found, on the one hand, to feed on sediment of rotten wood on the bottom of sea, while consumes hydrogen sulfide on the one hand, a gas released from the bottom of the sea bay by rotting vegetation or animal bodies.

In addition, it requires symbiotic bacteria to digest inorganic compounds.

Copyright © 2017