Guest commentary by Zhang Bei

Populism framed Western politics in 2016. The US presidential election, from the Sanders Phenomenon to Trump’s eventual victory, offered clear evidence of a surge of populism in the US, while across the Atlantic, Europe’s situation seems equally febrile.

The Brexit vote, which sent shockwaves across the globe and plunged the UK’s future into great uncertainty, had everything to do with rising populism in the UK. The referendum was put forward precisely because the establishment party could not resist the pressure of an insurgent right-wing populist party gaining ground. Following various grand arguments made by Brexiteer campaigners, 52 percent of Britons voted to leave the EU simply to “take their country back.”

Supporters of the Vote Leave campaign cheer during the first day of a nationwide bus tour to campaign for Brexit in Truro, UK on May 11, 2016. /CFP Photo

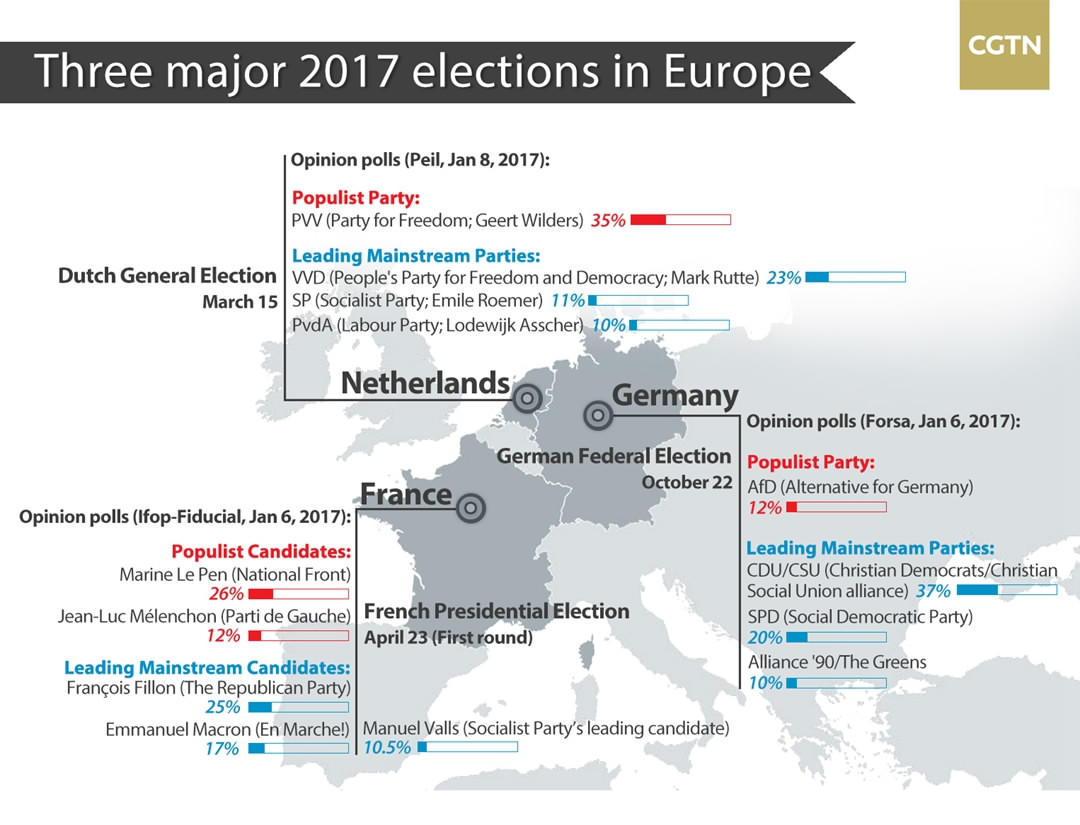

However, Brexit is only one explosive expression of a populist undercurrent that has been bubbling in Europe for a number of years. A major development unfolded in 2014 when populist Eurosceptic parties achieved historical breakthroughs in European Parliament elections. The National Front in France, Ukip in the UK and the Danish People's Party in Denmark all topped the polls in their respective countries. Over the years, Europe’s right-wing populist parties, such as AfD party in Germany, have gradually gained ground in regional elections, while national support for right-wing populists like Marine Le Pen in France and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands are soaring to make them serious competitors in coming national elections. In northern Europe, the nationalist, populist Finns Party, previously known as the True Finns, is the second largest party in parliament, and in the south the Syriza party is now governing Greece and a similar leftwing populist Podemos is waiting for its time in Spain.

It is no exaggeration to say that almost all major populist parties in European countries have gained in strength to varying degrees and their successes have even pushed some traditional established parties to espouse certain populist elements.

Marine Le Pen, leader of the French National Front(C), speaks to journalists during the inauguration of her presidential campaign headquarters in Paris, France, on November 16, 2016. /CFP Photo

Historical populism was born in the 19th century, and has since left an indelible mark in modern world history. Europe also experienced the rise and fall of populism throughout the last century. However, the concept is not easy to define. Unlike conservatism or liberalism, it is not an ideology but encompasses a general political mindset, value orientation and social trend. Usually, it calls for a rejection of elite politics and provides simplified answers to various problems in complicated politics. It is not a doctrine but a syndrome. The rise of populism is like a fever in a sick body. This is exactly what is happening to today’s Europe.

The populist sentiment currently flowing through Europe is a post-ideological reality enlarged by recession, globalization and the dramatic crisis of the political parties and representational elites. Populist movements across Europe may have many differences, some of which may come from opposing ends of the political spectrum, but they share many things in common.

Firstly, almost all of the current European populists are suspicious or even hostile towards the European Union. Ukip played a major role before and during the Brexit referendum campaign, and populists in both France and the Netherlands have called for similar polls in their own countries. Secondly, they are all anti-immigrant in the name of preserving native culture. The stance of Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and the Austrian presidential candidate Norbert Hofer on immigration has earned them a reputation of xenophobia. Thirdly, they reject political correctness on many issues and attack established politics for being out of touch with the will of the people.

The current surge of populism can be attributed to many difficulties Europe is facing.

First and foremost, the negative effects of economic globalization and European integration, coupled with aging social systems and unresponsive industrial policies, have greatly reduced the competitiveness of European economies. High unemployment and fading prospects for life betterment have led many Europeans to believe they have been left behind by globalization and ignored by the governing elites.

The EU’s poor economic performance and ineffective or even divisive policies, the bail-out programs for instance, have greatly weakened its reputation. Added to its complicated and sometimes bureaucratic institutions and working styles, the EU is an easy target and scapegoat for Europe’s problems given the bloc’s establishment symbolism. Opposing the European project has also become the main prescription European populists are offering.

The final factor is probably the trickiest. The ongoing influx of immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East has created big economic and more importantly social problems for Europe. It is entangled with a security threat posed by radical Islam and so-called culture conflict that is proving a near unsolvable conundrum for lawmakers. This issue has torn European society apart and has also created fertile land for populism.

Europe’s elites are grappling with rising populism. They were relieved that the Austrian far-right candidate lost the presidency, but in France, Germany and the Netherlands populist forces, benefiting from frequent terrorist attacks, will pose real challenges to traditional parties in elections this year. Europe may not end up having a populist leader, but the force behind the populist surge is ominous enough. It is a sign that something is seriously wrong with the liberal order, open border and democratic system that Europe has championed. Clearly, populism won’t provide a cure, and European elites must take action before it’s too late.

(Edited by John Goodrich and Wang Xuejing)