Long before they conquered ancient Egypt, cats seduced Stone Age farmers who launched the worldwide feline takeover of human homes and hearts, a DNA study showed on Monday.

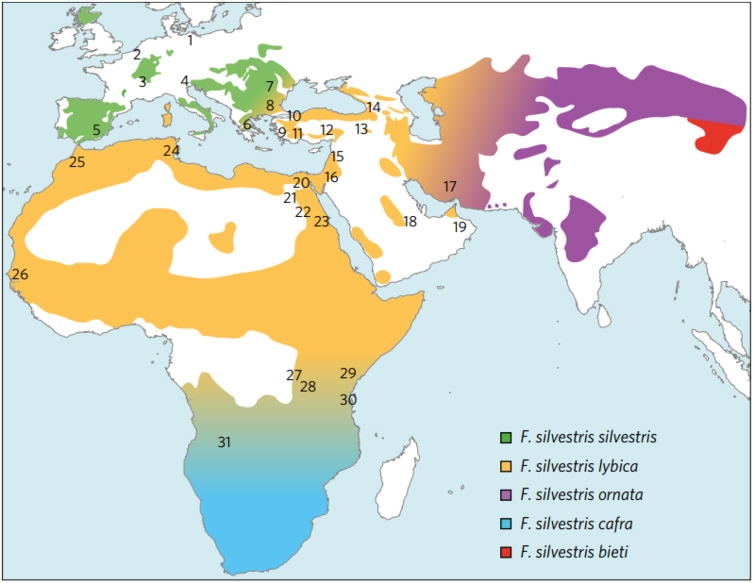

The first wildcat to travel abroad, and the forefather of domestic cats today, was Felis silvestris lybica – a small, striped Middle-Eastern sub-species that went on to colonize the entire world, the research revealed.

It likely traveled to Europe by ship from the region of Anatolia around modern-day Turkey, some 6,000 years ago.

"The cat's worldwide conquest began during the Neolithic period," the study authors wrote.

Felis silvestris lybica /VCG Photo

The Neolithic was the closing chapter of the Stone Age – a time when prehistoric humans, hunter-gatherer nomads until then, first tried their hand at cultivating crops and building permanent villages.

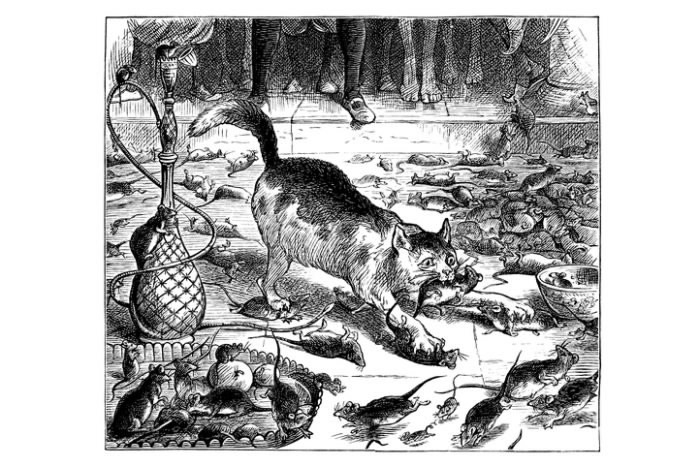

With farming came harvest-munching rats, which in turn attracted cats.

"For ancient societies barn cats, village cats and ships' cats provided critical protection against vermin, especially rodent pests responsible for economic loss and disease," the researchers wrote in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The researchers obtained DNA from hundreds of cats including cat mummies. /Nature Photo

Ancient 'fad'

The team analyzed the DNA of 230 buried and mummified ancient cats in a bid to settle the debate over who was responsible for turning the wild feline into the cuddly couch-slouches we know today.

Based on their obvious reverence for the feline – immortalized in statues, paintings and even mummified carcasses – the ancient Egyptians were thought by many to have been the first cat tamers several centuries BC.

But others have pointed to a cat skeleton found in a child's tomb in Cyprus from 7,500 BC, as proof that ancients from the Fertile Crescent beat the Egyptians to it.

The cat's ability to keep rodents under control was one reason it was domesticated. /Nature Photo

The DNA trawl shows we can thank both.

F. s. lybica, the researchers found, "started to spread at times when the first farmers started to migrate into Europe" around 4,400 BC, said study co-author Eva-Maria Geigl of France's CNRS research institute.

"This can be taken as indication that they were trans-located by humans, either by ship or on the ground", probably following ancient trade routes.

A few thousand years later, in the time of the pharaohs, an Egyptian variant of lybica also spread in a second wave into Europe and beyond, sparking somewhat of a "craze", the study authors said in a statement.

The modern distribution of the five subspecies of F. silvestris; only one, F. s. lybica, has been domesticated, but that domestication occurred twice, in both southwestern Asia and Egypt. Numbers here refer to locations of samples used in the study. /Nature Photo

"This fad for Egyptian cats very quickly spread through the ancient Greek and Roman world and even much further afield".

Given that it would have looked a lot like its close cousin from Anatolia, the researchers speculate that the Egyptian cat's success was likely driven by its personality – "changes in its sociability and tameness".

500 million domestic cats

Wildcats are solitary, territorial hunters with no hierarchical social structure – seemingly poor candidates for domestication.

Yet today, there are an estimated 500 million domestic cats in the world – one for every dozen or so people.

The F.s. family: F. silvestris, or European Wildcat (Left top); F.s. bieti, or Chinese Mountain Cat (Left bottom); F. s. lybica, or African Wildcat (Middle); F.s. cafra, or Southern African Wildcat (Right top), and F.s. ornata, or Asiatic Wildcat (Right bottom). /Nature Photo

The ancestor, F. s. lybica, is one of five wildcat sub-species still found in nature today. It lives in North Africa and around the Arabian Peninsula.

Over millennia, domesticated cats interbred with other wildcat sub-species – including European – that they encountered on their global conquest.

As a result, many European wildcats also have a bit of domestic cat, with lybica origins, in their genome today.

The study revealed that unlike for dogs or horses, humans did not breed cats for their looks – at least for the first few thousand years.

Even to this day, domestic cats closely resemble their wild cousins in terms of body build, function and behavior.

Felis silvestris lybica /VCG Photo

Dogs, by comparison, range in breed from a Rottweiler to a Chihuahua – neither of which reminds one of their wolf forefathers.

When it started, selective breeding targeted mainly the cat's coat. The first time that a tabby coloring enters the gene record is during the Middle Ages, between the years 500 and 1300, the researchers found.

The spotted or blotched tabby pattern common in house cats today, does not exist in wildcats, which are all striped.

"Only recently, during the 19th century, there were breeding programs to obtain 'fancy breeds'," said Geigl, adding even these are "not very different from the wildcat."

(Source: AFP)