Culture & Sports

11:53, 12-Oct-2016

Ancient Buddhist murals highlight Xinjiang's fascinating religious past

Updated

10:19, 28-Jun-2018

Today in China’s Uygur Autonomous Region, the major religion is Islam. Prior to the arrival of Islam, it was Buddhism. One of the greatest legacies from that time are the murals, in the "Grottoes of Qiuci", another name for the ancient kingdom of Kucha.

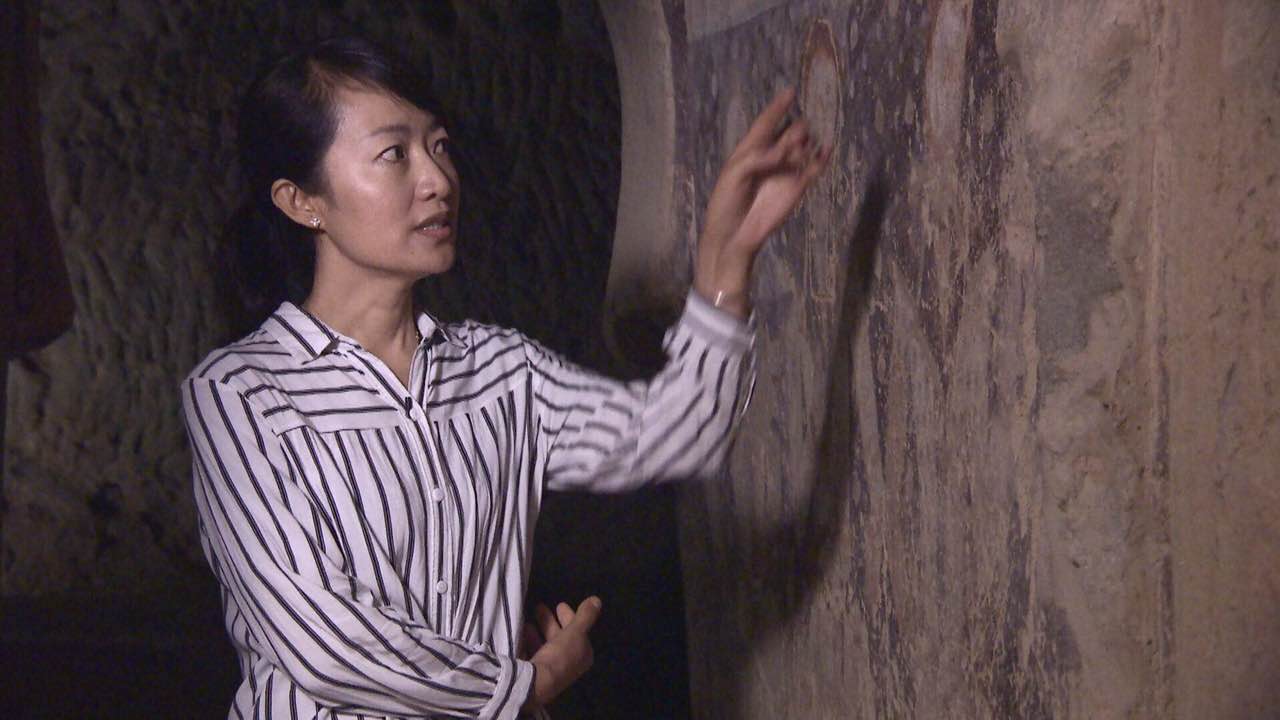

“I’ve always been curious to study how murals drawn some 2,000 years ago, have survived to this day. How can we better protect them to extend their survival in the future?” said Ye Mei, Director of Insititue of Qiuci Grottoes protection, who has been investigating these secrets for 18 years.

The Qiuci Grottoes is the most famous Buddhist art site in China’s Uygur Autonomous Region. The influence of the different civilizations from the West and the East were profound. For a long time, Qiuci was the most populous oasis in the Tarim Basin.

Ye told us the grottoes house the cultural achievements of the region's ancient ethnic groups. They show that ancient civilization was built on the integration of the dominant Buddhist culture with several other religious cultures.

“Qiuci was a very inclusive and prosperous society. It was a key hub of the ancient Silk Road, a key melting pot for different cultures. These characteristics are fully reflected in the paintings,” she said.

The murals are rich and diverse in content. But time and the elements have taken their toll. The actual number of grottoes and murals is still a mystery.

Every day, Ye Mei and her team are hard at work, high up in the mountains. Most of the caves are closed to the public.

The team keeps detailed records and identifies the cause of the damage to determine the best course of action.

Ye Mei says the speed of restoration cannot catch up with the speed of deterioration.

“We strictly follow the concept of modern relic protection. We try to minimize human intervention, achieve material compatibility, and maintain historical authenticity,” said Ye.

“The techniques and material used in mural restoration are still in a long process of research. What we are using is obtained through years of testing and analysis,” she added.

In her eight-hour work day, no detail is too small.

“The murals are a precious cultural heritage left by our ancestors. They are also a valuable world heritage that needs our great protection. I will be their life-long companion. A little shake might remove a piece of history from the wall; my hands can also help stabilize them in the original form. This is my greatest joy,” she said.

Ye said that she wants to restore Qiuci as closely as possible to its former glory so that the legacy of the lost oasis can one day be viewed by all.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3