Business

16:18, 21-Mar-2017

The rise of populism doesn't equate to rejecting globalization

Updated

11:06, 28-Jun-2018

Some say 2016 was the year that populism defeated globalization. One could be tempted to agree – after all, Donald Trump has now moved into the White House and the UK has voted to leave the European Union. But the truth, as always, is much more complex.

The terms globalization and populism are often bandied about without clear definitions.

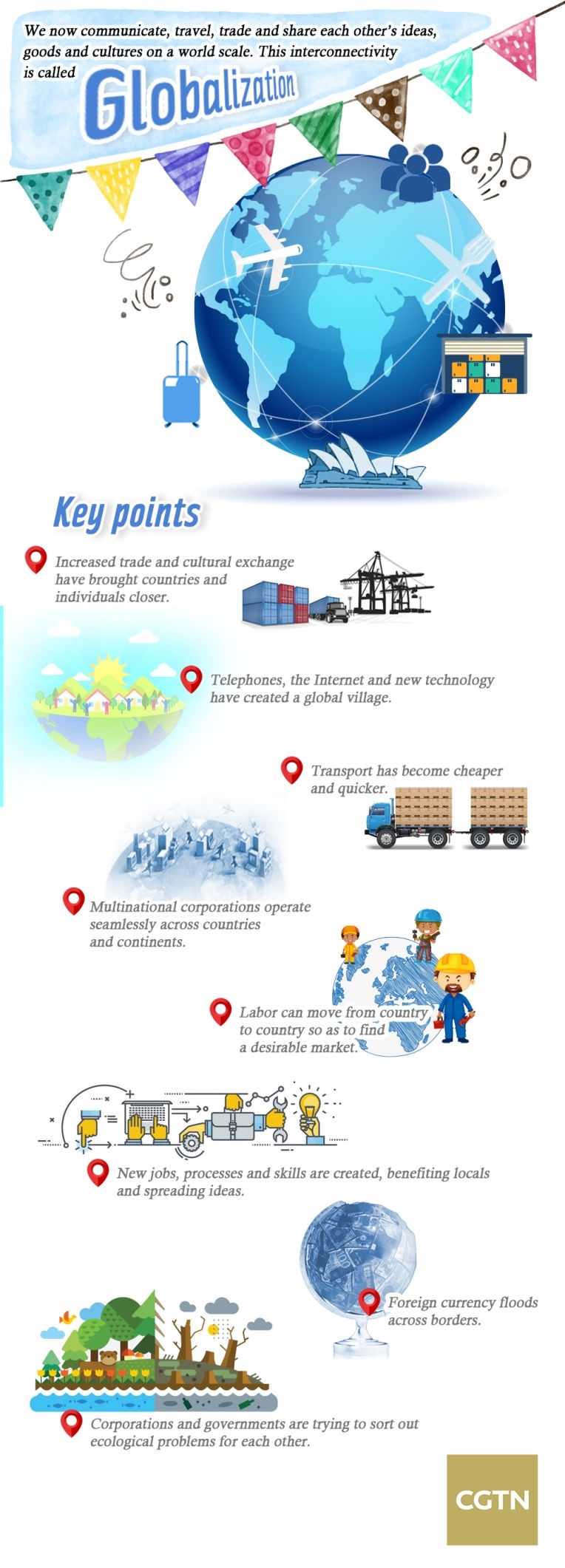

Globalization involves, among other things, factors like the Internet, cheap travel and cheap goods - things few of the so-called populists would be keen to lose.

Jan-Werner Müller, a political scientist at Princeton University, thinks populists are defined by their claim that they alone represent the people, and that all others are illegitimate.

Some scholars link populism to frustration over declines in status or welfare, some to nationalist nostalgia. Others see it as more of a political strategy in which a leader appeals to the masses while sweeping aside institutions. Despite its fuzziness, the term’s use has grown.

The populist revolt is more cultural, less economic

Rising populism has disrupted the politics of many Western societies. To explain this phenomenon, the most widely held view is economic distress.

Alternatively, another theory suggests a retro reaction by once-predominant sectors of the population to progressive value change.

In a study of rising populism, political scientists Pippa Norris of Harvard's Kennedy School and Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan carefully examined the two arguments. They concluded that economic insecurity in the face of workforce changes in post-industrial societies was a less valid explanation than cultural backlash.

Their extensive research indicates that since 1970, the cultural shift among the young and the better-educated strata of society has fostered greater approval and social tolerance of diverse lifestyles, religions, and cultures, multiculturalism, international cooperation, democratic governance, and protection of fundamental freedoms and human rights.

But the spread of progressive values has also stimulated a cultural backlash among people who feel threatened by these developments. Less educated and older citizens, especially white men, who were once the privileged majority in Western societies, resent being told that traditional values are “politically incorrect” if they have come to feel that they are being marginalized within their own countries. As cultures have shifted, a tipping point appears to have occurred.

In the US, polls show that Trump’s supporters are skewed toward older, less-educated white males. Young people, women, and minorities are under-represented in this coalition.

Rise of populism doesn’t signal demise of globalization

A poll released in September 2016 by the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations found 65 percent of Americans agree that globalization is mostly good for the US, while Americans’ support for free trade has trended up since the recession, not down.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Trump has railed against free trade, but that appears less central to his electoral success than opposition to immigration and broader racial anxiety on the part of a fairly narrow slice of the population.

In fact, the US economy has increased its dependence on international trade. According to World Bank data, from 1995 to 2015, merchandise trade as a percentage of total GDP has increased by 4.8 percentage points. Moreover, in the age of the Internet, the transnational digital economy’s contribution to GDP is rapidly increasing.

In 2014, the US exported 400 billion US dollars in information and communication technologies-enabled services - almost half of all US services exports.

Globalization has done the world a lot of good. Research from the McKinsey Global Institute shows that, thanks to global flows of goods, services, finance, data, and people, world GDP is more than 10 percent higher – some 7.8 trillion dollars in 2014 alone – than it would have been had economies remained closed.

So, while 2016 may have been the year of populism in politics, it does not follow that globalization is in retreat. Globalization is like being overwhelmed by a snow avalanche. You can’t stop it – you can only swim in the snow and hope to stay on top.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3