Chinese, US scientists make first reversal of pest resistance to GM cotton

2017-05-09 14:56 GMT+8

10642km to Beijing

Editor

Xie Zhenqi

The issue of pest resistance to genetically modified (GM) crops has received widespread attention worldwide. But Chinese and US researchers have found a solution, revealing on Monday the success of a surprising new strategy for countering the problem.

In a study published in the US journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers reported that hybridizing genetically engineered cotton with conventional cotton reduced resistance in the pink bollworm, a voracious global pest.

The findings were based on an 11-year study, in which researchers at the Chinese Academy Of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) and the University of Arizona (UA) tested more than 66,000 pink bollworm caterpillars from China's Yangtze River Valley, a vast southeastern region that is home to millions of smallholder farmers.

According to the study's authors, this is the first reversal of substantial pest resistance to a crop genetically engineered to produce pest-killing proteins from the widespread soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt.

More than 66,000 pink bollworm caterpillars were tested in the long-term study. /UA Photo

"This study gives a new option for managing resistance that is very convenient for small-scale farmers and could be broadly helpful in developing countries like China and India," study co-author Kongming Wu, who led the work conducted in China and is a professor in the CAAS's Institute of Plant Protection in Beijing, said in a statement.

Crops genetically engineered to produce insecticidal proteins from Bt kill some major pests and reduce use of insecticide sprays.

However, evolution of pest resistance to Bt proteins decreases these benefits.

The primary strategy for delaying resistance is providing refuges of the pests' host plants that do not make Bt proteins. This allows survival of insects that are susceptible to Bt proteins and reduces the chances that two resistant insects will mate and produce resistant offspring.

Before 2010, the US Environmental Protection Agency required refuges in separate fields or large blocks within fields.

Cotton cropping systems in China, such as the patchwork of farms along the Yangtze River Valley, are quite different from the large-scale systems used for cotton in the US and Australia. "In China, there are many small-scale mixed plantings of cotton, corn, soybean, peanut and other crops that are owned and managed by individual small farmers," says Kongming Wu. /UA Photo

Planting such non-Bt cotton refuges is credited with preventing evolution of resistance to Bt cotton by pink bollworm in Arizona for more than a decade.

By contrast, despite a similar requirement for planting refuges in India, farmers there did not comply and the pink bollworm rapidly evolved resistance.

The new strategy used in China entails interbreeding Bt cotton with non-Bt cotton, then crossing the resulting first-generation hybrid offspring and planting the second-generation hybrid seeds.

This generates a random mixture within fields of 75 percent Bt cotton plants side-by-side with 25 percent non-Bt cotton plants.

"We have seen blips of resistance going up and down in a small area," said senior author Bruce Tabashnik, a professor in the UA's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. "But this isn't a blip. Resistance had increased significantly across an entire region, then it decreased below detection level after this novel strategy was implemented."

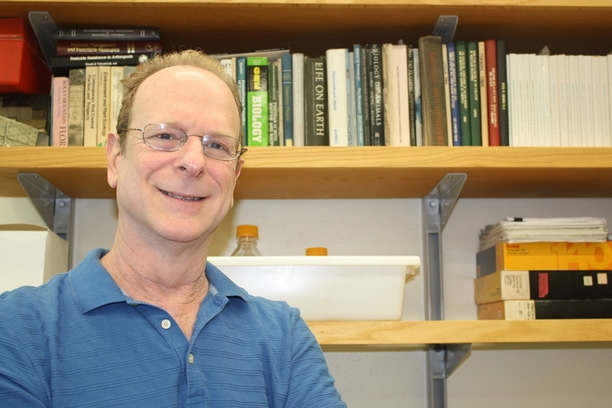

Bruce Tabashnik, head of the UA Department of Entomology, works with Chinese scientists on monitoring and countering pest resistance to genetically engineered crops. /UA Photo

Tabashnik called this strategy revolutionary because it was not designed to fight resistance and arose without mandates by government agencies. Rather, it emerged from the farming community of the Yangtze River Valley.

"For the growers in China, this practice provides short-term benefits," Tabashnik added. "It's not a short-term sacrifice imposed on them for potential long-term gains. The hybrid plants tend to have higher yield than the parent plants, and the second-generation hybrids cost less, so it's a market-driven choice for immediate advantages, and it promotes sustainability."

(Source: Xinhua)

10642km

Copyright © 2017