World

16:02, 27-Feb-2018

UK slavery tweet rekindles Caribbean reparations bid

By Bertram Niles

A surprise tweet from the British Treasury acknowledging that a debt to UK transatlantic slave owners had been fully repaid only in 2015, nearly 200 years later, has given new life to the campaign for slavery reparations in the Caribbean.

In 2013, the governments of the region created the Caribbean Reparations Commission to establish the moral, ethical and legal case for the payment of reparations by former colonial powers "for the crimes against humanity of native genocide, the transatlantic slave trade and a racialized system of chattel slavery."

Although a UK law firm has since been engaged to help prepare a legal case, the campaign seemed to be running out of steam, at least publicly.

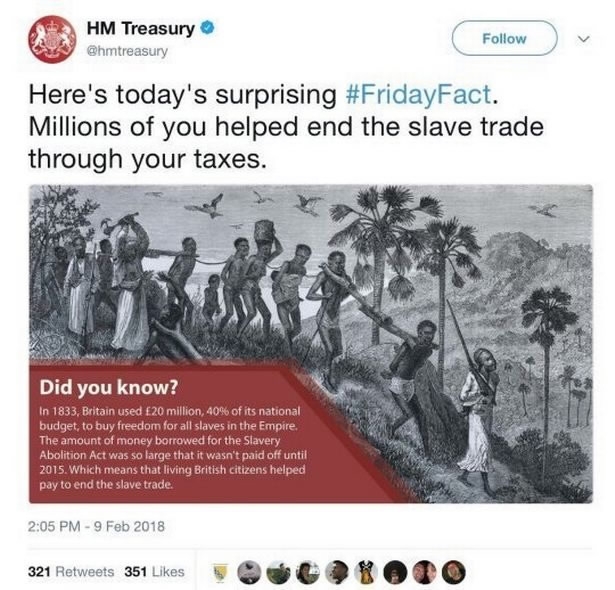

That was until the Treasury, in a response to a newspaper's freedom of information request, told the nation in a tweet that millions of Britons "helped end the slave trade through your taxes."

Screenshot of UK Treasury tweet which was quickly deleted.

Screenshot of UK Treasury tweet which was quickly deleted.

The commission's chairman seized upon the new information by calling a news conference in Jamaica to express his indignation at British "public dishonesty" over the Caribbean claim for compensation over the trade, which lasted from the 16th to the 19th century.

Sir Hilary Beckles, referencing a speech in the island in 2015 by then British Prime Minister David Cameron that urged the region to "move on" from slavery, said, "For me it is the greatest act of political immorality to be told consistently and persistently to put [slavery] in the past and yet Her Majesty's Treasury has released the relevant information to suggest that it is just two years ago that this bond was being repaid."

He said the revelation made the issue a priority for Britain and the commission will be pushing the governments of the region to put pressure on Europe for talks on reparations.

Slavery ended throughout the Caribbean in the 1800s in the wake of slave revolts. The 20 million pounds the British government paid slave owners to compensate them in 1833 was a huge amount of money, equivalent to 40 percent of the national budget at the time.

Monument commemorating the emancipation of slaves in Barbados.

Monument commemorating the emancipation of slaves in Barbados.

In a speech last October, Beckles, a historian and vice chancellor of the University of the West Indies, put the debt's value at 76 billion pounds today (106 billion US dollars) – the sum he said should now be paid to the descendants of slaves in the Caribbean.

Opinions on reparation in the region are divided. Some see it as delayed justice, others as an empty claim and a distraction from modern social problems in local societies.

But the end of slavery left the economies of the island nations in disarray and the effects are still being felt today, the governments have said. Slavery "has contributed to the burden of poverty which most of our countries face,” Beckles contends.

The Caribbean's 10-point plan envisages a full formal apology for slavery, repatriation to Africa, a development plan for the native Caribbean peoples and funding for cultural institutions.

It also seeks to address chronic diseases and psychological rehabilitation for trauma inflicted by slavery, technology transfer to make up for technological and scientific backwardness resulting from the slave era, and support for payment of domestic debt and cancellation of international debt.

French historian Jean-Michel Deveau has called the slave trade and consequently slavery, one of "the greatest tragedies in the history of humanity in terms of scale and duration."

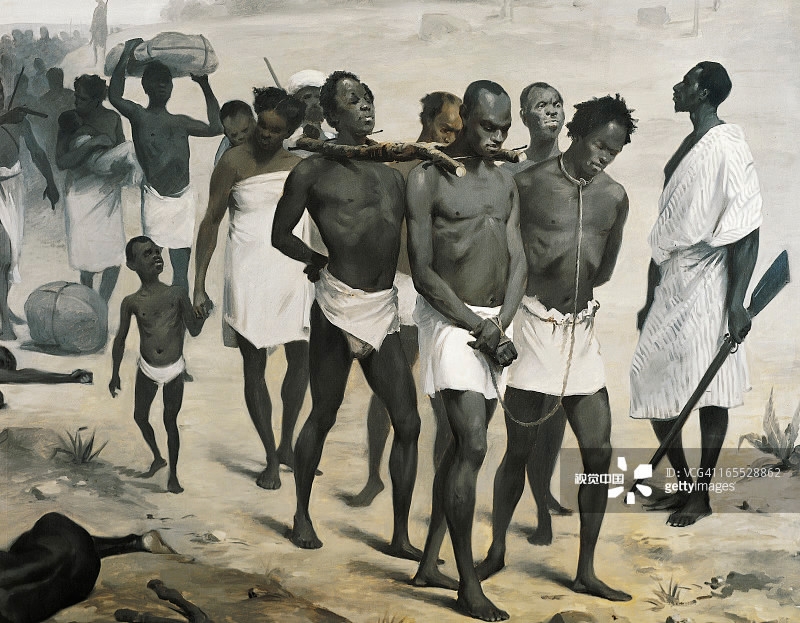

The transatlantic slave trade is regarded as the biggest deportation in history. /VCG photo

The transatlantic slave trade is regarded as the biggest deportation in history. /VCG photo

Between 10 million and 12 million enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas in terrible conditions, according to historians. These figures exclude those who died aboard the ships and in the course of wars and raids connected to the trade.

The UK Treasury's tweet, displaying apparent smug satisfaction that the taxes of present-day Brits helped to "end" slavery, also led to a backlash at home that forced its hasty deletion.

"Is this really something we should regard with collective pride?" asked historian and television presenter David Olusoga in the Guardian.

"Few people in the 1830s would have seen it that way," he continued. "Compensation was a mechanism by which Britain was finally able to end a system that millions of people had come to regard as abhorrent, and a national disgrace."

A black local government councilor in the southwestern English city of Bristol, which had close links to the slave trade, launched an online petition on behalf a global group of campaigners to demand a "full" refund of money that went to paying off the debts of slavery.

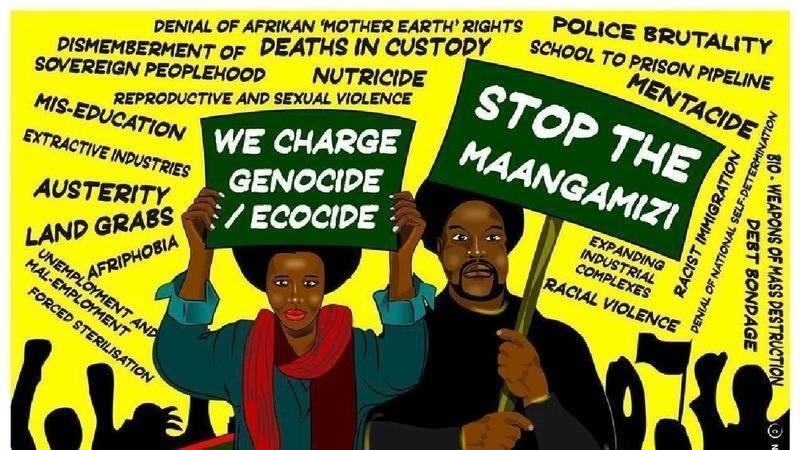

More than 1,000 people have signed the petition on change.org for a British government refund of "our taxes paid to compensate enslavers." This poster greets visitors to the page.

More than 1,000 people have signed the petition on change.org for a British government refund of "our taxes paid to compensate enslavers." This poster greets visitors to the page.

“The notion that we as taxpayers in Britain, including those whose ancestors were subjected to the horrors of enslavement, have by your own admission, financially contributed to such payments, is totally unjust and abhorrent to us,” said Cleo Lake of the Global Afrikan People's Parliament.

Britain as the primary slave power and colonial power in the Caribbean faces the largest reparations claim but other European states targeted are France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

Just what happens next is unclear and analysts say the Caribbean faces an uphill task in getting these nations to the table as they, in the words of David Cameron, want to "move on from this painful legacy and continue to build for the future."

The legal case is considered even more tenuous with one Cambridge University legal scholar memorably describing it as “an international legal fantasy.”

If, for example, the Caribbean is thinking of taking the case to the International Court of Justice, one of the stipulations that Britain made on joining is that it cannot be tried for any actions before 1974.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3