Business

19:30, 06-Sep-2017

China's involvement could tilt the global oil game on its axis

CGTN

If you open up any newspaper in the world, there is a good chance you'll find a news story about the oil prices going in one direction or the other. To some average consumers, it is possible to get the impression that the prices are in a "spot market" - that is, they'd pay the current price and accept delivery within a few weeks.

The reality is not that straightforward. The price of oil as we know it is actually set in the oil futures market. An oil futures contract is a binding agreement that gives a consumer the right to purchase oil by the barrel at a predefined price on a predefined date in the future.

Most of the trillions of dollars of oil traded each year is priced off two crude derivatives, US West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and London’s Brent, and executed mainly on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) owned by CME Group and Intercontinental Exchange.

China, as the world's second-largest economy, buys more oil than any other nation, but that doesn't mean it always gets the best prices.

To expand the country’s influence on global markets, China is preparing to launch its own derivative crude contract on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange, known as INE, that would better reflect market conditions in the region.

China's first oil futures contract on the way

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

The long-awaited crude oil futures contract is likely to make its trading debut in the next few months, as the Shanghai Futures Exchange and its subsidiary INE successfully completed four tests in the production environment for the crude oil futures last month, and the Exchange presses on with preparatory works for the listing of crude oil futures.

This will be China's first commodities futures contract that is open to foreign companies, including investment funds, trading houses, and petroleum companies.

So will China's participation be a game changer for the industry?

The renminbi denominated futures contract could become the most important Asia based crude oil benchmark, given that China is the world's biggest oil importer.

It could also help China shift the pricing of oil away from the US dollar, a move that China has already encouraged with some of its trading partners. China proposed pricing oil in Renminbi to Saudi Arabia in late July, according to a Daily Reckoning report.

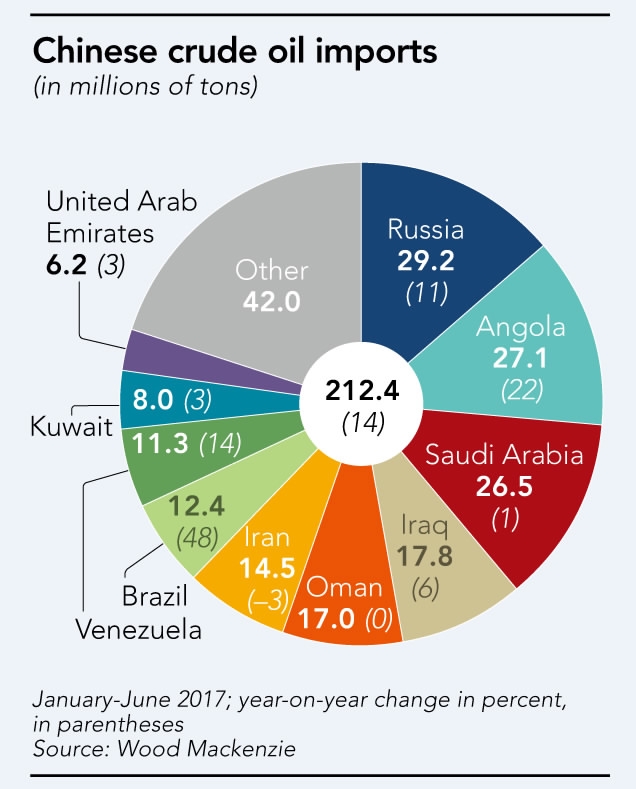

Saudi Arabia shipped 26.5 million tons of oil to China in the first half of 2017, making it China's third-largest oil supplier, and ranked first on the list is Russia, according to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

The Shanghai futures exchange could allow Russia to circumvent US dollar trade, to bypass US sanctions by trading in renminbi - and this logic also applies to Iran.

Thorns on path to rosy future

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

Some potential foreign traders have been worried that the contract would be priced in renminbi. However, China says the renminbi will be fully convertible into gold on exchanges in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Backing the renminbi priced futures with gold would be appealing to oil exporters, especially to those that would rather avoid trading in US dollars.

Russia may now sell oil to China for renminbi, then take whatever excess currency it earns to buy gold in Hong Kong. As a result, Russia does not have to buy Chinese assets or switch the proceeds into dollars.

Traders also expressed concern over lack of liquidity as the industry remains very much dominated by state giants.

It is understood that the market will also be open to retail investors. The Shanghai futures contract will be traded at 100 barrels of oil per lot, instead of 1,000 barrels for both Brent and WTI.

Locally registered entities of JPMorgan and UBS are among the first to have gained approval to trade the contract. State-backed oil majors, such as PetroChina and Sinopec will provide liquidity to ensure trade.

The exact terms for delivery of oil associated with the futures contracts have yet to be unveiled. The physical oil underlying Shanghai’s crude futures could be a challenge.

Unlike WTI or Brent, which are priced off a small amount of similar crude grades from the same area, Shanghai’s futures are to be priced from a variety of crudes from the Middle East and China. Since these crudes vary in quality and price, there was disagreement over how to weight the different grades within Shanghai crude futures benchmark, traders said.

Still, commodity futures initiated in China have a history of gaining popularity quickly. Iron-ore futures traded on the Dalian Commodity Exchange have seen explosive growth since their October 2013 debut, for example.

“Just the sheer size of China’s untapped market and its expected growth in oil consumption is enough to justify its own pricing benchmark,” Gao Jian, a Shangdong based commodity analyst at SCI International, told the Wall Street Journal.

But, he said, it could take “anywhere from 10 to 30 years” for Shanghai to have an oil benchmark to rival Brent and WTI.

1069km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3