Politics

21:05, 16-Mar-2018

China’s education reform: Study hard, for what?

CGTN's Li Jingjing, Dean Yang

Chinese school students are among the most under pressure in the world, toiling for hours every day to develop their talents.

On average, Chinese children spent 8.1 hours at primary school on weekdays and 11 hours a day in high school, according to a 2015 study by China Youth and Children Research Center (CYCRC), a government body.

Schoolwork also bites into their home time. A 2017 survey by Afanti, an education firm, found that homework took up nearly three hours a day for Chinese school students, 3.7 times more than their Japanese counterparts and 4.8 times that of South Korean kids.

In addition to weekday work, extra-curricular activities on weekends took up another 2.1 hours of supposed leisure time, the CYCRC study reported. All these rates are the highest in the world.

On the back of the mounting pressure is the toll on young people’s health. From 2002 to 2012, the obesity rate among Chinese aged six to 17 increased by 4.7 percentage points, according to a report by China’s public heath authority. Half of all students aged seven to 15 were near-sighted in 2014.

Both the system and those within it; from students to parents, educators to officials, are crying out for reform to ease the burden. During this year’s two sessions, China’s ongoing top legislative event, the issue of reducing workload for school children has been raised yet again, but a comprehensive solution probably remains out of sight.

In the context of China’s economic success, the education system should have served the country well. It has always had a clear objective to fill in relation to the national development, from the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to the market open-up in 1980s.

This has painted Chinese education in a somewhat “utilitarian” light. As the country shifts the focus of growth from accumulation of state wealth to improved individual wellbeing, it seems only natural that education of the old pragmatic philosophy is struggling to keep up.

Why study hard?

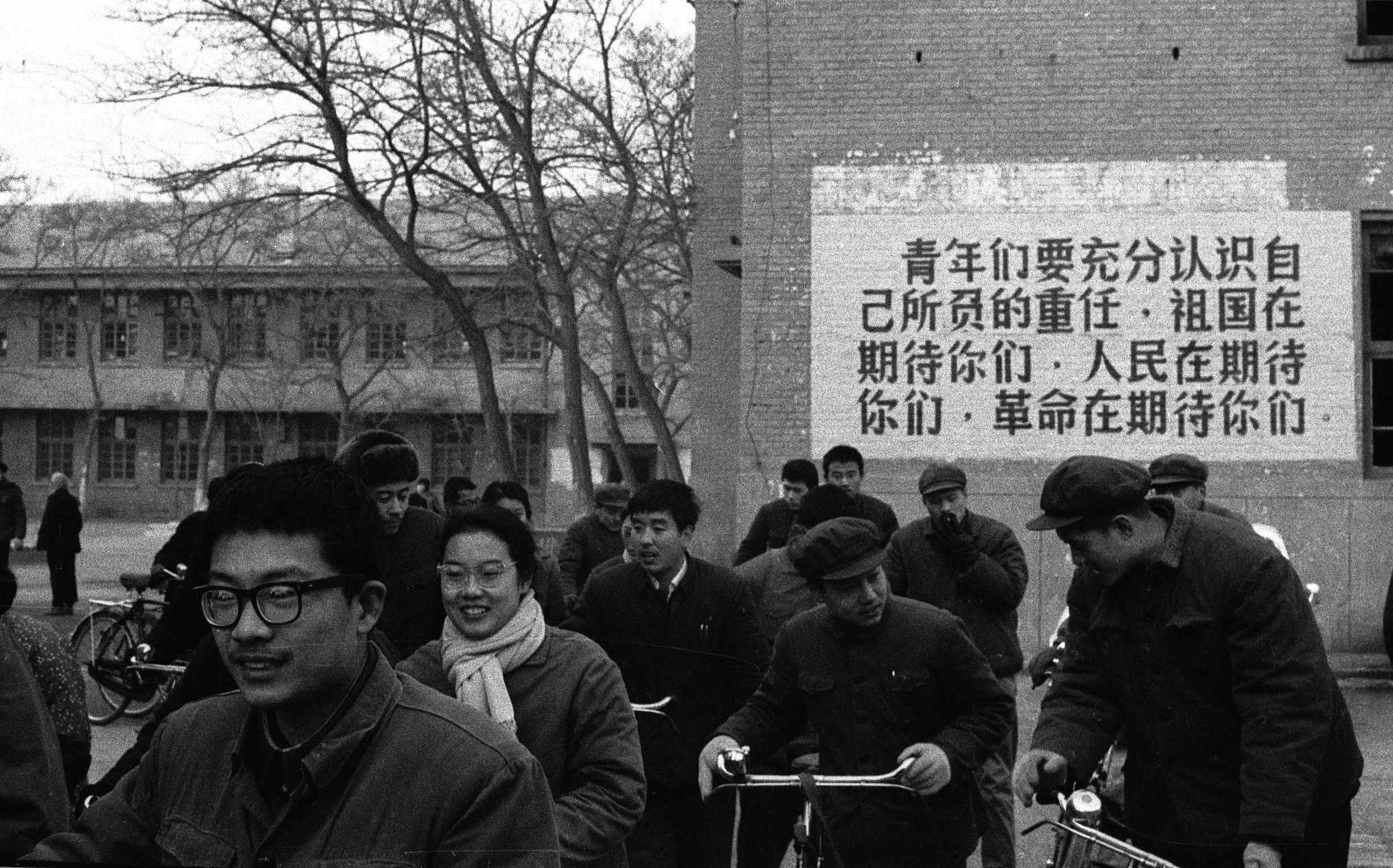

"Young people must bear in mind their responsibities to the country, to the people and to the revolution", says the banner outside a local College Entrance Examination location in Beijing, December, 1977. VCG Photo

"Young people must bear in mind their responsibities to the country, to the people and to the revolution", says the banner outside a local College Entrance Examination location in Beijing, December, 1977. VCG Photo

At the dawn of the PRC, the country’s economy was in ruins after years of devastating war. The then Soviet Union’s education system provided a template that featured mobilization of national resources to increase manpower in the economic sectors key to growth. In this manner, the Chinese government started to reshape its education infrastructure, giving universities and schools an assisting role during the young republic’s laborious reconstruction.

The relationship between education and the country’s development has been stressed in the following decades. But the purposes that education needed to serve have been adjusted in line with different developmental stages.

For the decades after China began opening-up, the thought that technology was crucial to development began to resonate increasingly on the one hand, the influence of an ever freer market started growing on the other.

Together with the impact of the still dominant state-owned players in the economy, the concepts, though not necessarily in conflict with each other, created different interpretations of the “meaning” of education among the general public.

Migrant workers perpare to go home after failed adventure in Beijing, March 14, 1991. VCG Photo

Migrant workers perpare to go home after failed adventure in Beijing, March 14, 1991. VCG Photo

Following years of economic deprivation before the reform, desires for consumer goods exploded. Businesses burgeoned as the market liberalized. With profit-driven salaries they soon became a magnet for people who feared falling back into poverty. Yet labor-intensity and low added value remained a hallmark for manufacturers, private and state-owned alike, for many years to come. Commercial ambition was prioritized over a college degree.

A belief in getting rich fast appealed to many. Four years in university seemed an unnecessary luxury cost, despite the government’s effort to enhance the status of education. “Reading is useless” became a battle cry for the new money as China’s economic boom accelerated, cementing education’s utilitarian role by negating its non-commercial benefits.

According to official archives, 5.7 million candidates sat the college entrance examination in 1977 (it had been suspended for the previous decade) and only 270,000 were admitted. However, the number of those taking the exam didn’t exceed five million again until 2002, despite a steadily growing population.

A sales assistant rests her eyes in a state-owned shop in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, 1992. VCG Photo

A sales assistant rests her eyes in a state-owned shop in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, 1992. VCG Photo

Meanwhile, the sway of state-owned enterprises was felt in the market as well as in ordinary people’s lives. Graduating from high school to become a trained worker in a state-owned factory remained a popular choice for many. A state-backed company appeared to offer security – people believed they would never be laid off, but the tuition fee for a college degree might not pay off.

Data from the official Employment and Composition in Urban Units by Registration Status showed that the number of workers in state-owned businesses rose from 80 million in the 1980s to 110 million in 1997 when the downsizing campaign first kicked in.

Entering the 1990s, the danger of inflation loomed ever larger as a result of years of double-digit growth, incurring government interference to cool down the overheating economy that had a toll on employment. At the same time, the deepening state-owned-enterprise reforms saw millions lose their jobs.

Still along the utilitarian line, the importance of education in relation to job security began to sink in. This was when a timely policy to increase university enrollment was introduced in 1999 that served a purpose, among others, of restructuring the country’s labor market.

The next year saw 2.2 million candidates succeed in securing higher education positions. The number had grown more than threefold in 2016 to 7.7 million. The number of higher education institutions more than doubled between 2000 and 2016, from 1,041 to 2,596, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

The bandana reads "conquering college entrance exminations", Hengshui No.2 High School, Hebei Province, February 26, 2018. VCG Photo

The bandana reads "conquering college entrance exminations", Hengshui No.2 High School, Hebei Province, February 26, 2018. VCG Photo

Many have benefited from the expanded investment in education. However, the utilitarian view has changed little. Panic has arisen again for parents and students who view going to university as nothing more than a path to a secure career of financial stability.

More aggressive competitions have scaled up for better resources. A seat at a top university requires quality education in a top-rated high school, which in turn is contingent on better teachers and working environment of an elite junior high, if not on a reputable primary school.

The pressure has prompted parents to push children to the limit to add even one more point to the final grading in the entrance examinations of any level. This eagerness has contributed to the national boom in extra-curricular businesses that promise to enhance students’ performances at exams, or to train them in an art or sport.

Instead of discovering young talents and encouraging them to develop, these firms merely offer embellished applications. These activities increase not only the workloads for young students, but also financial pressure on the parents.

The market for off-school curriculums was valued at 300 billion yuan (around 47 billion US dollars at today’s rate) in 2005. Ten years later, the total valuation had reached 800 billion yuan, according to official calculations. Research by Peking University estimated that nearly 48 percent of all Chinese school students had taken part in such courses in 2017.

Schools and teachers have their own performance assessment often pinned on students’ grades in the “life-determining” exams. This has made educators more easily complicit in increasing work for teenagers than defending students’ wellbeing.

Many experts and education practitioners have already pointed at the assessment system to be the fundamental cause of the problem: if students go to school for nothing, but increasing their grades in the entrance exams, that will alone determine their future.

“To study hard so that you can get a good job and make more money has become what many Chinese parents expect of their children, and this has caused the students’ backpacks to be heavier and heavier,” said You Lizeng, a high school teacher who is also a lawmaker of China’s National People’s Congress.

Even with a root cause identified, an institutional overhaul has proved tricky. This is particularly true about the college entrance examinations: to test students in the fields of Chinese, science, math and English with a set of relatively uniformed exams nationwide is widely believed to be the only fair system. Any attempt to “tamper” with it by making it more creative would increase the education cost and tip the balance in favor of well-off students – if the balance didn’t lean that way already. Diversifying assessment systems or delegating assessment to universities has also added to concerns over corruption.

Hu Wei, a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s top political advisory body, suggested that more efforts should be put into making the assessment more inclusive, so that the students can be confident about finding their own ways of succeeding.

China’s central government has pledged to continue reducing burdens for school students in 2018, according to the government work report that was released on March 5. More important still is the report’s wording of the passage on the task of reforming China’s education system, promising a holistic approach in the future:

“We need to…ensure that every individual has an equal opportunity to change their life and realize their dreams through education.”

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3