Tech & Sci

22:05, 31-Jul-2017

Lugworm, from fish hook to a bringer of medical miracles

For centuries, the only use humans found for the lugworm – dark pink, slimy and inedible – was on the end of a fish hook.

But the invertebrates' unappreciated status is about to change. Their blood, say French researchers, has an extraordinary ability to load up with life-giving oxygen.

Harnessing it for human needs could transform medicine, providing a blood substitute that could save lives, speed recovery after surgery and help transplant patients, they say.

Marine worms may hold the key to medical breakthroughs including speedier recovery from surgery and more blood transfusions. /AFP Photo

Marine worms may hold the key to medical breakthroughs including speedier recovery from surgery and more blood transfusions. /AFP Photo

"The haemoglobin of the lugworm can transport 40 times more oxygen from the lungs to tissues than human haemoglobin," says Gregory Raymond, a biologist at Aquastream, a fish-farming facility on the Brittany coastline.

"It also has the advantage of being compatible with all blood types."

Raymond and his team, which specializes in fish egg production, joined forces with biotech firm Hemarina in 2015 in the hope of securing a reliable means of lugworm production.

The facility now churns out more than 1.3 million of the creatures each year, each providing tiny amounts of the precious haemoglobin.

Marine worms are better known as providing bait for fishermen. /AFP Photo

Marine worms are better known as providing bait for fishermen. /AFP Photo

"We started basically from zero. Since the worm had never been studied, all parameters needed inventing from scratch, from feeding to water temperature," says project researcher Gwen Herault.

Medical interest in the lugworm – Arenicola marina – dates back to 2003, when the outbreak of mad-cow disease in Europe and the worldwide HIV epidemic began to affect blood supplies.

The problem was that animal haemoglobins, as a substitute for the human equivalent, can cause allergic reaction, potentially damaging the kidneys.

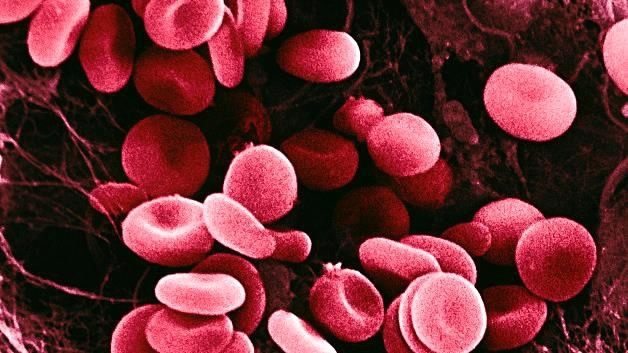

In lugworms, though, haemoglobin dissolves in the blood and is not contained within red blood cells as in humans – in other words, blood type is not an issue – and its structure is almost the same as human haemoglobin.

Red blood cells. /VCG Photo

Red blood cells. /VCG Photo

In 2006, the worm's potential was validated in a major study.

Scientists at Roscoff, close to Plomeur, extracted and purified haemoglobin from local-caught lugworms and tested it on lab mice. The rodents were fine and showed no sign of the immune response that dogged other animal substitutes.

If proven safe for humans, the researchers said, the worms' oxygen-rich blood could tackle septic shock – a crash in blood pressure that can cause fatal multiple organ failure – and help to conserve organs for transplantation.

Clinical trials of the blood product began in 2015. Lugworm haemoglobin was used last year in 10 human kidney transplants at a hospital in the western French city of Brest and 60 patients are currently enrolled in tests of the blood product across France.

(Source: AFP)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3