Climate

18:04, 17-Nov-2017

UN climate talks wrap up as US stands firm on fossil fuels

CGTN

Delegates at the United Nations climate conference reported mixed progress on the final day, with the re-emergence of divisions between rich and developing countries.

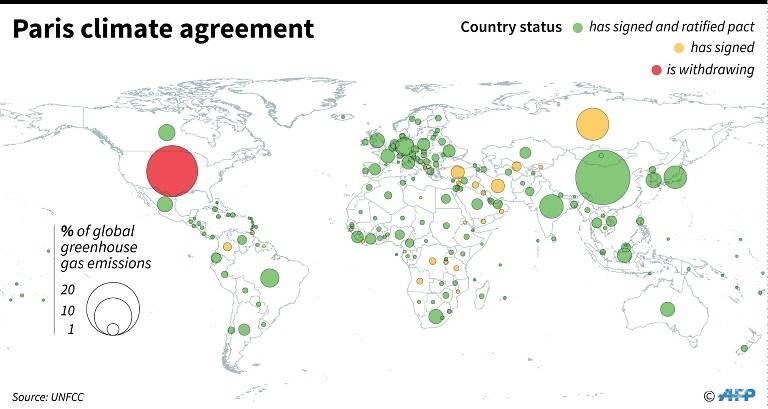

Envoys from nearly 200 countries have been meeting for nearly two weeks in Bonn to negotiate a "rulebook" to be adopted next year, for enacting the global deal reached to cheers and champagne in 2015.

A key stumbling block during the Nov. 6-17 conference was finance for the world's poorer nations to help them prepare for, and deal with, the fallout from climate changes – including more frequent and severe superstorms, droughts and land – and crop-gobbling sea level rises.

AFP Photo

AFP Photo

AFP Photo

AFP Photo

Another obstacle was the insistence of developed nations – led by the US – that all countries share similar obligations under the Paris pact, while developing greenhouse gas polluters want a certain degree of leeway.

The conference is the first of the UN's climate body since President Donald Trump announced in June that the US will withdraw from the agreement championed by his predecessor Barack Obama.

The rules determine it can only leave in November 2020, and in the meantime, Washington continues to fill its seat at the climate talks.

At the UN climate conference, people pass the German pavilion in the shape of the Earth. /AP Photo

At the UN climate conference, people pass the German pavilion in the shape of the Earth. /AP Photo

"The stars are not well aligned since Trump's exit from the pact," said Seyni Nafo, a negotiator for African nations.

"It's like the heart wasn't there. The position of the United States influences other developed countries, which in turn has consequences for the positions major developing nations adopt. It's a game of wait-and-see."

Not helping the mood, White House officials hosted a sideline event with energy company bosses Monday to defend the continued use of fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas blamed for emitting planet-warming gases into the Earth's atmosphere.

At its very essence, the Paris Agreement seeks a drawdown of carbon emissions.

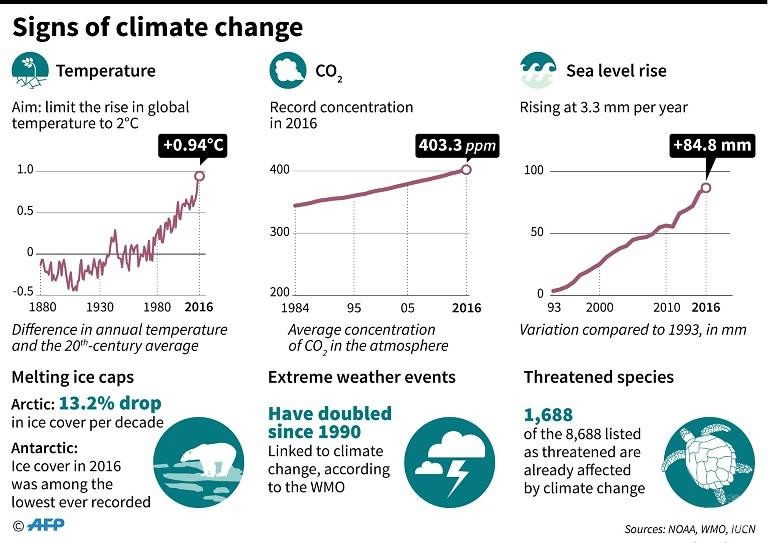

The pact commits countries to limiting average global warming to under two degrees Celsius over Industrial Revolution levels, and 1.5 C if possible, to avert worst-case-scenario climate change.

Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama speaks during the opening session of the UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn./Reuters Photo

Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama speaks during the opening session of the UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn./Reuters Photo

'Ridiculous'

Nations submitted voluntary emissions-cutting commitments to bolster the deal, but scientists say the pledges place the world on course for a warming of 3 C or more.

How, and when, to update country commitments to bring them in line with the 2 C target, is a central topic in the ongoing negotiations.

"Our task has been made all the more difficult with the disengagement of the world’s largest historic emitter from the Paris Agreement," Maldives environment minister Thoriq Ibrahim told delegates Thursday on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States at the forefront of climate change-driven sea-level rises.

The Trump administration insisted, however, that it was "committed" to limiting greenhouse gas emissions – as long as this does not threaten energy security or the economy.

The United States is the world's biggest historical greenhouse gas polluter. /Reuters Photo

The United States is the world's biggest historical greenhouse gas polluter. /Reuters Photo

Acting assistant secretary of state Judith Garber told the conference that the US would "support the cleanest, most efficient power generation, regardless of the source."

The United States is the world's biggest historical greenhouse gas polluter.

The negotiations will carry on without the US, and nations and businesses will continue moving away from fossil fuels, said Mohamed Adow of Christian Aid, which represents poor country interests at the talks.

He pointed to a coal phase-out initiative launched in Bonn Thursday with the backing of 20 countries led by Britain and Canada.

"But what we have lost is the diplomatic leadership of the US in driving the process," added Adow.

"We are missing the old US administration in lining up the politics."

Source(s): AFP

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3