Politics

20:30, 09-Dec-2017

Goats, Brexit and a struggle haunting the Irish border

By Jasmine Cen

You would think herding wandering goats is as simple as jumping a fence into a nearby field and rounding them up, but what if the next field, and the goats, are in another country?

The Ireland-UK border, the subject of historic dispute and struggle, has re-emerged as a political hot potato since the UK announced its intention to leave the European Union.

UK Prime Minister Theresa May and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker sealed a deal on Britain’s divorce from the EU on Friday, but only after a small Northern Irish party, the DUP – on whom May is reliant for votes in parliament – scuppered an earlier agreement over Irish border concerns.

Residents at the frontier feared an old dilemma was returning before Friday’s announcement. While people currently enjoy a seamless daily commute for work over the border and goods flow freely, the looming prospect of Brexit had threatened a return of checkpoints for goods and restricted travel.

On Friday, all sides were at pains to emphasize that a hard border would not return – but how the border will be policed post-Brexit is far from a settled issue.

How history relates to goat-searching?

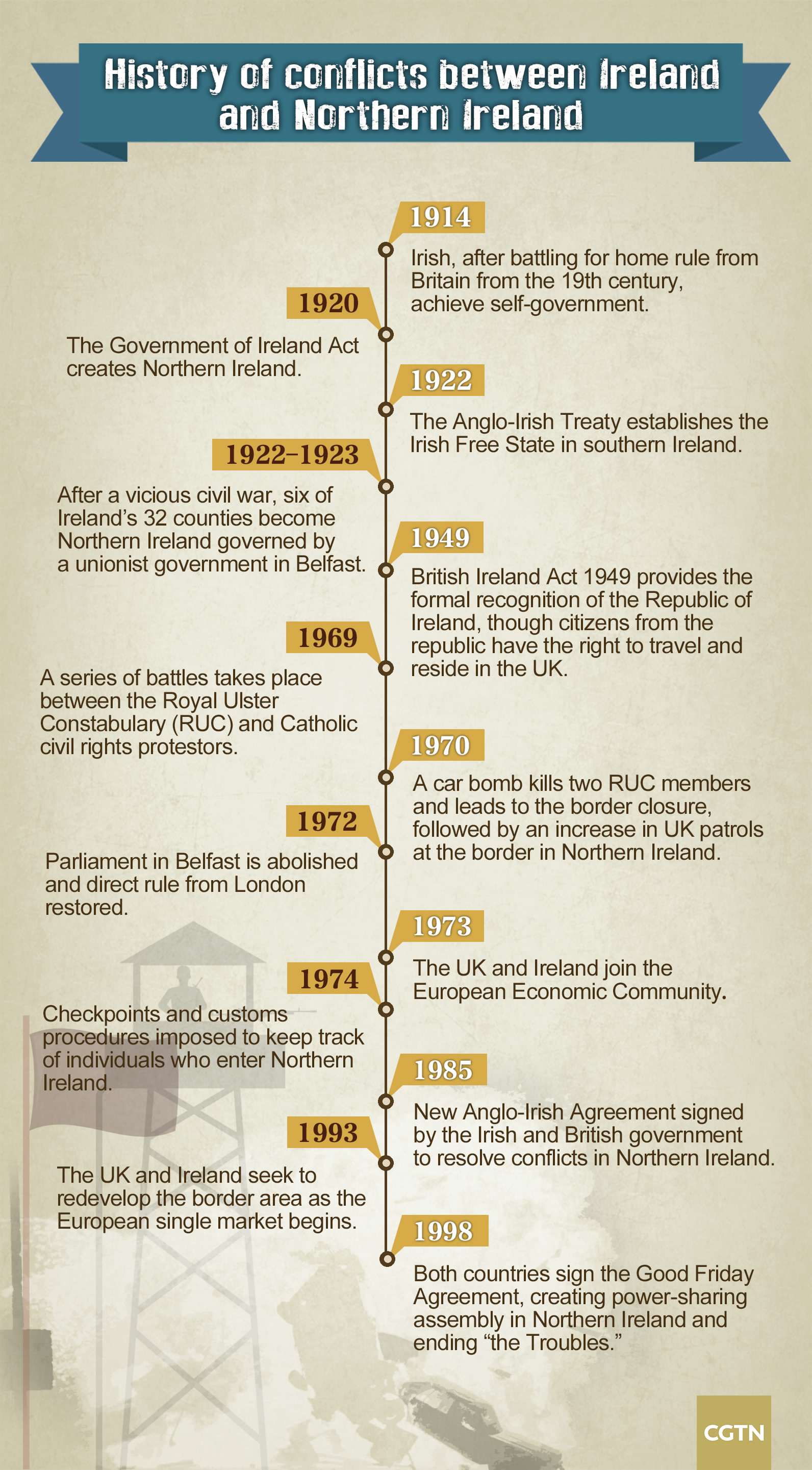

The 20th century was marked by an independence struggle on the island of Ireland, pitting republicans who wanted freedom from the British against unionists who wanted to remain part of the UK. The period of “the troubles” played out largely along religious lines, between Protestant unionists and Catholic nationalists.

The legacy of violence caused unease on both sides of the border as Brexit talks began in 2017, rekindling memories of a dispute that had taken decades to resolve.

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) had sought to create a united Ireland. It and other paramilitary organizations used guerrilla tactics against the British army and unionists in the hope of forcing the British to withdraw.

The violence that killed thousands ended with the Irish peace process, which was finally secured by the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The deal ended the chaos and provided a political framework for rivals to share power in Northern Ireland.

A Brexit warning sign sits beside the former border customs hut between Donegal in the Republic of Ireland and Londonderry in Northern Ireland. / Reuters Photo

A Brexit warning sign sits beside the former border customs hut between Donegal in the Republic of Ireland and Londonderry in Northern Ireland. / Reuters Photo

European Union membership was a key factor – both sides were in a common economic area, so border checks marking the partition were not needed.

What’s a goat got to do with it?

The Irish goat is a very old domestic breed that has long been kept for meat and milk, and likes to wander freely over the island from north to south and vice versa.

The Irish border slices through houses, farms and villages; sometimes cutting off homesteads from their farms. It can also place an invisible barrier between an escaped goat and a farmer.

The practical difficulties of creating a hard border are enormous. According to data provided by borderroadmemories.com, there are 275 crossings at the UK-Ireland borderline, which is more than the total number of crossings at the EU’s eastern frontier.

Anti-Brexit campaigners, Borders Against Brexit, protest outside Irish Government buildings in Dublin, Ireland, April 25. / Reuters Photo

Anti-Brexit campaigners, Borders Against Brexit, protest outside Irish Government buildings in Dublin, Ireland, April 25. / Reuters Photo

Dr. Katy Hayward, a professor at Queen's College Belfast, insists that the long-time struggle haunting the Irish border will remain dormant. “The result of the UK referendum in no way diminishes the capacity for strong, peaceful and mutually beneficial relations to continue across the Irish border,” Hayward said.

The seamless frontier has been an essential component of the peace process, so achieving a compromise that keeps all sides happy is essential.

So, what are the options for the goats?

Goats are probably more concerned with freedom of movement than tariff-free trade. Under the plan agreed on December 8 both are possible, but not certain.

Notably, a compromise, rather than a binding and specific deal, on the Irish border has been agreed to allow Brexit talks to move forward.

Staunch unionists the DUP secured a guarantee that there will be no regulatory barriers between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, while all sides said that there will be no hard border and the Good Friday agreement would be upheld.

A sign saying "No Border, Hard border, soft border" in Londonderry, Northern Ireland on August 16. / Reuters Photo

A sign saying "No Border, Hard border, soft border" in Londonderry, Northern Ireland on August 16. / Reuters Photo

So although goats, goods and people will be probably be able to roam free, the deal presents an apparent contradiction. How can the UK leave the European single market and customs union but also have an open border?

The answer may lie in the future talks over a free trade deal between the UK and the EU. But for now, there is no clarity over how an open border can be achieved – only that all sides are determined to avoid a return to checkpoints.

It was feared that one day soon a farmer might stand at the edge of the frontier where the EU meets the UK, while goats chewed up the grass along the borderline. Although much is still to be decided, the December 8 deal appears to blow off concerns over a hard border. Farmers will still be able to cross countries to herd their goats, even after the UK leaves the EU.

(CGTN's John Goodrich contributed to this story.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3