World

12:10, 28-Sep-2017

Rohingya children at risk during Myanmar refugee crisis

By Joshua Barlow

As the Rohingya refugee crisis in Myanmar continues to worsen, aid workers are struggling to protect those most vulnerable – among them unaccompanied children.

Christophe Boulierac, a UNICEF Geneva Spokesperson, said the children "…deserve a very specific protection, not only nutrition, health, but also we need to protect these children so that they don’t go into prostitution, they don’t face abuses."

In response, Child Welfare officers, UNICEF, and other charities have been setting up child-friendly zones throughout the Bangladesh refugee camps.

These safe havens, such as those at Kutapalong Camp near Myanmar’s border, offer extra protection for children who’ve made the journey there without family to help them.

A Rohingya refugee shelters from the sun under an umbrella while looking at the refugee camp of Balukhali, near the locality of Ukhia on September 21, 2017. /AFP Photo

A Rohingya refugee shelters from the sun under an umbrella while looking at the refugee camp of Balukhali, near the locality of Ukhia on September 21, 2017. /AFP Photo

Mohammad Ramiz, a 12-year-old Rohingya child at Kutapalong, spoke about making the journey alone.

"I came here by crossing a river three days ago with several adults. I ate leaves from the trees and drank water to survive."

According to UN estimates, more than half the current Rohingya refugees are children. Many of them say they’ve witnessed family members brutally killed in village massacres in Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

"A bullet killed my father when he went to the market during last year’s violence," 10-year-old Yasmine Akhtar told CGTN. "This time they burnt my mother. I was terrified and I hid in a paddy field when I saw a big group of people walking towards me. I joined that group and came here.”

According to Reuters, southwest Bangladesh’s largest hospital said a third of the wounded refugees are children. Most of them injured by gunshots or bomb blasts.

Abdullah, an 11-year-old Rohingya child at Kutapalong, was one of those injured during the trek.

A young Rohingya refugee shelters from the rain with an umbrella while sitting at Kutupalong refugee camp in the Bangladeshi locality of Ukhia on September 19, 2017. /AFP Photo

A young Rohingya refugee shelters from the rain with an umbrella while sitting at Kutupalong refugee camp in the Bangladeshi locality of Ukhia on September 19, 2017. /AFP Photo

"I was bleeding and could not even lift my hand. I had to find a stick and with the support of the stick I slowly walked with other people to come here. After I arrived, I was taken to the hospital."

The Rohingya are a poor, unrepresented Muslim minority who live in predominantly Buddhist Myanmar (formerly Burma). Myanmar has long denied citizenship to the Rohingya.

The current crisis began on August 25 after a group of Rohingya insurgents in Myanmar’s Rakhine State attacked more than 30 police stations, killing 12 officers.

Government security forces responded with a crackdown on Rohingya villages, alleging rebels were hiding among the general population.

Since then, more than 410,000 Rohingya civilians have fled their homes. Many have accused state security and Buddhist mobs of attacking them indiscriminately, burning their houses, and worse.

Myanmar State Councilor Aung San Suu Kyi has refuted these claims, blaming terrorists for an "iceberg of misinformation" about the violence.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman has said China will help its neighbor "… uphold internal stability and development."

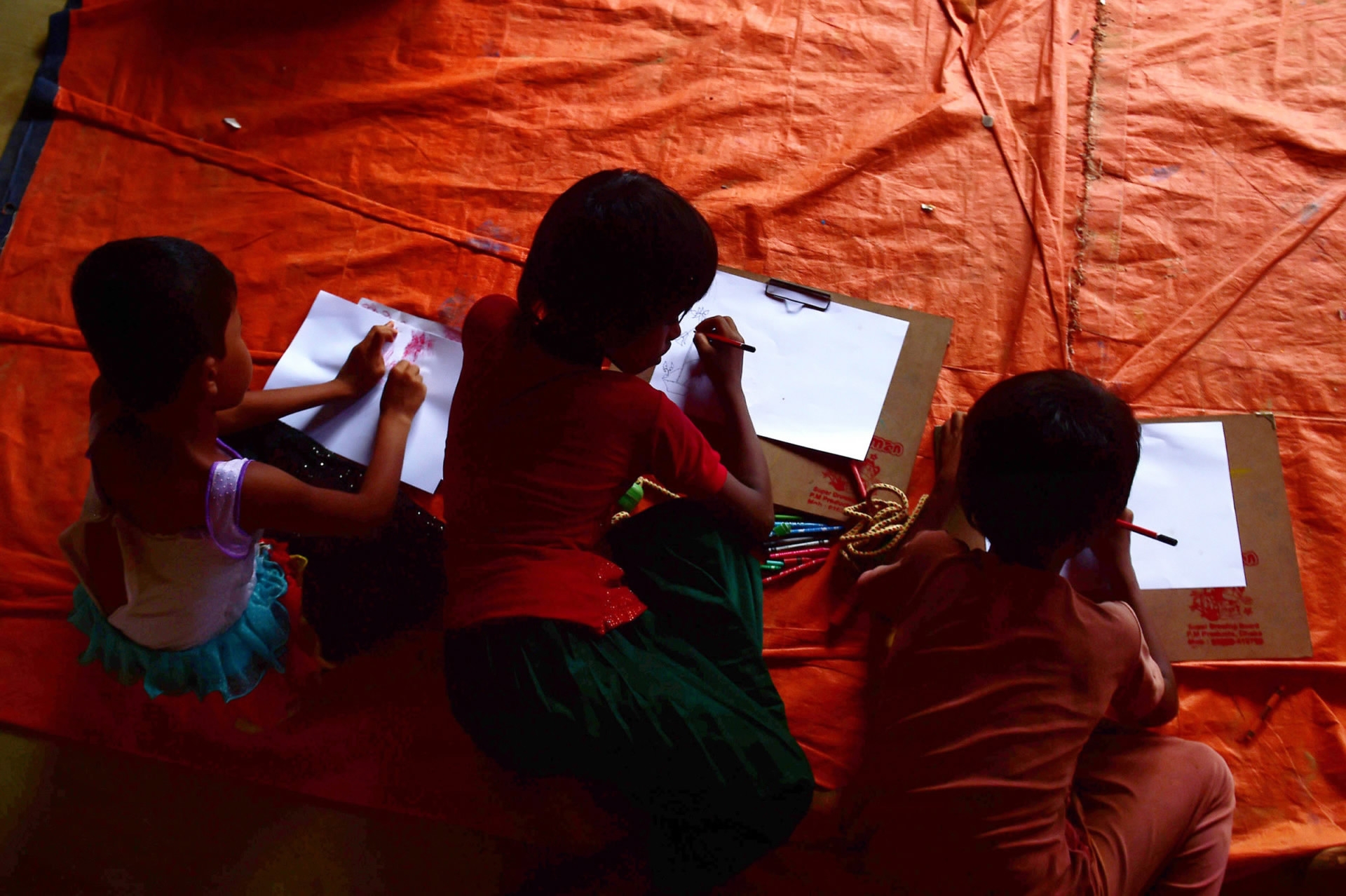

In this photograph taken on September 11, 2017, Rohingya Muslim refugee children draw pictures at a safe house in Kutupalong refugee camp in the Bangladeshi town of Teknaf. /AFP Photo

In this photograph taken on September 11, 2017, Rohingya Muslim refugee children draw pictures at a safe house in Kutupalong refugee camp in the Bangladeshi town of Teknaf. /AFP Photo

To reach safety in neighboring Bangladesh, refugees have crossed treacherous jungles, mountains – and rough seas in the Bay of Bengal. All during the height of monsoon season.

While Bangladesh has made efforts to accommodate the refugees, there are shortages of food, water, medicine and shelter. At many camps, there is little or no sanitation.

In addition to the UN’s stationary child protection zones, UNICEF says there are nearly three dozen mobile units in Bangladesh. Each of them offers health care, and provides games and educational materials. They’re also staffed with teachers and counselors to provide emotional support.

Such resources may not be enough. Over a 48-hour period at Kutupalong in September, more than 2,000 children came through just a single "safe zone".

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3