Politics

10:45, 01-Jan-2017

Park Geun-hye - a president, puppet or plotter?

Updated

10:29, 28-Jun-2018

-South Korean President Park Geun-hye impeached amid influence-peddling scandal

-Millions of South Koreans take to the streets week after week to call for her resignation

-Park alleged to have allowed a long-time friend to influence political decisions for personal gain

As crowds of fellow South Koreans protested outside the presidential complex in Seoul in late November, Park Geun-hye cut an isolated figure. She was under intense pressure to resign as president – or be forced out.

Sections of her own Saenuri party had abandoned her, opposition groups threatened to impeach her and public displeasure on the streets was mirrored in the polls – her popularity rating slumped to a record low of four percent at the beginning of December, according to Gallup Korea.

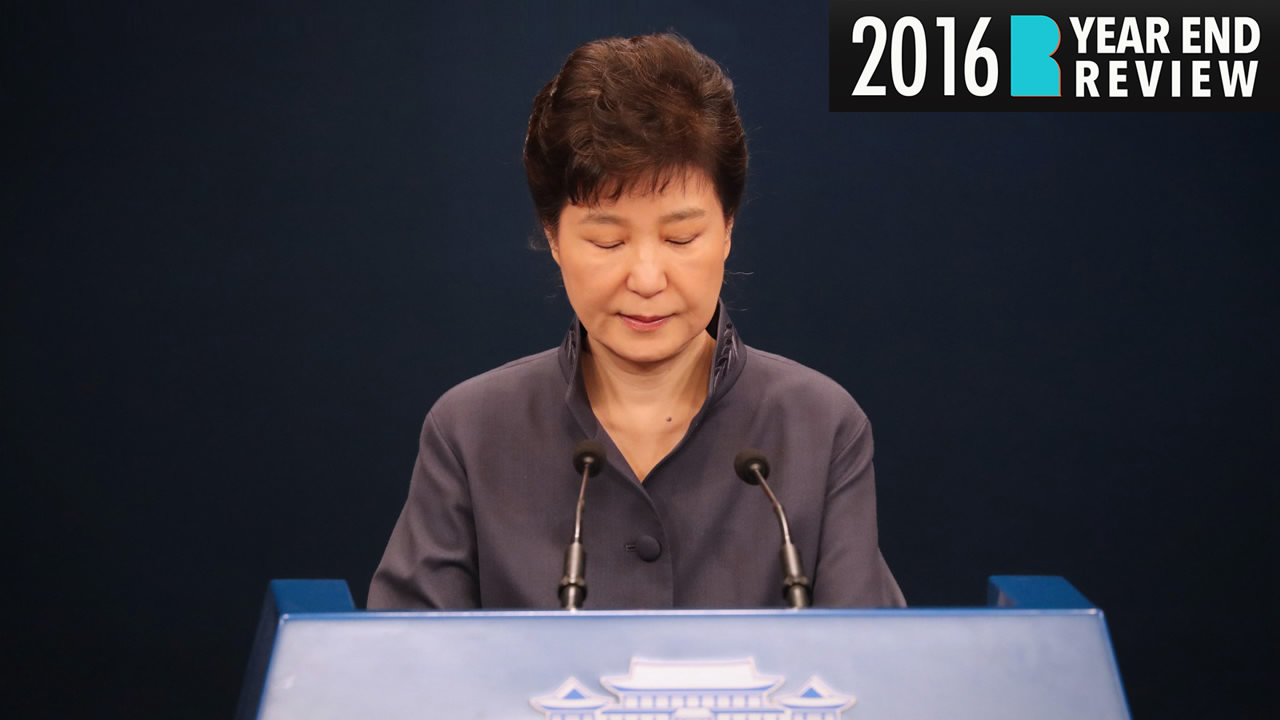

Park Geun-hye bows to public, apologizing for leaking government documents to confidante, October 26,2016. /CFP Photo

Park Geun-hye bows to public, apologizing for leaking government documents to confidante, October 26,2016. /CFP Photo

Barely over a month earlier, on October 24, Park had proposed amending the South Korean constitution to allow presidents to serve multiple terms. The 64-year-old would not have benefitted directly from the change, but the proposal was nevertheless treated cautiously by rival parties.

Why now, they asked? To give Park relevance as the typically lame duck end to her five-year term approached? Or to distract from another story that was bubbling below the surface?

A former presidential secretary Ahn Jong-beom arrives for questioning at the Seoul Central District Prosecutors' Office in Seoul, South Korea, November 2, 2016. /CFP Photo

A former presidential secretary Ahn Jong-beom arrives for questioning at the Seoul Central District Prosecutors' Office in Seoul, South Korea, November 2, 2016. /CFP Photo

The same day, South Korean media outlet JTBC revealed evidence that Park’s long-time confidante Choi Soon-sil had received secret government documents.

The friends met in the 1970s when Park’s father, Park Chung-hee, was South Korean president. Choi's father, cult leader Choi Tae-min, became close to the presidential family and a mentor to both the then president and the younger Park. When he died, his daughter replaced him as head of the Eternal Life Church and has offered Park Geun-hye spiritual guidance ever since.

Choi Soon-sil returns to Seoul, South Korea on October 31, 2016. /CFP Photo

Choi Soon-sil returns to Seoul, South Korea on October 31, 2016. /CFP Photo

Park was accused in the press of colluding with Choi, who has since been charged with abuse of power, fraud and coercion, to pressure major South Korean corporations into donating to two foundations - both controlled by Choi.

The confidante is also alleged to have used some of the funds for her personal use. And Park has apologized for giving Choi inappropriate access to government decisions.

Two former aides to Park, An Chong-bum and Chung Ho-sung, have also been charged in the affair, and the leaders of major businesses – including Samsung, Hyundai and Lotte – have been questioned by MPs about whether their companies made donations in exchange for political favors.

After weeks of mass protests on the streets of Seoul, Park offered to resign on November 29 if parliament could set out an appropriate way to maintain stability in the country.

Park's close friend Choi Soon-sil to face interrogation, November 3, 2016. /CFP Photo

Park's close friend Choi Soon-sil to face interrogation, November 3, 2016. /CFP Photo

But the decision was taken out of her hands. Opposition parties rejected her offer, and an impeachment motion was put to the 300-strong parliament on December 9. It was passed by 234 lawmakers with 56 opposed, and although Park retained the trappings of office, her powers were suspended until a constitutional court ruling on the motion.

Prime Minister Hwang Kyo-ahn, who was fired by Park on November 2 in the middle of the crisis but remained in office, assumed her presidential responsibilities on a temporary basis.

The nine judges on the constitutional court have up to 180 days to decide whether to reject the motion or uphold it and remove Park from office. If at least six judges uphold the motion, Park will become the only South Korean president to be removed in the country's democratic era.

Tens of thousands of protestors gathered in Seoul to make Park resign, November 5, 2016. /CFP Photo

Tens of thousands of protestors gathered in Seoul to make Park resign, November 5, 2016. /CFP Photo

And Park’s problems may not end there – without the immunity afforded a sitting president, she could also face trial. She has apologized for personal mistakes while denying wrongdoing, but the investigating prosecutor has already said he thinks she may have been complicit in the scheme for which Choi was charged.

South Korean law states a general election must take place within 60 days of a president stepping down or being removed from office, so a poll to replace Park could take place in the first half of 2017.

Possible contenders are already lining up, with defeated 2012 Democratic United Party candidate Moon Jae-in and Seongnam Mayor Lee Jae-myung among the hotly-tipped names. But could an outsider be in with a shot? Former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon, who has just left office after two five-year terms, has hinted that he might be willing to swap the blue helmets for the Blue House.

Questions for 2017:

-Will Park be removed from office? The constitutional court must decide whether to permanently remove her by mid-2017. And if she is removed, will she face trial?

-Who are the candidates to replace Park? If removed, a new election would be held within 60 days. Could former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon be a contender?

-How would a new president impact affairs in the region? Will the THAAD deployment go ahead? How will the DPRK react to instability in the south?

(Written by Li Yezi; Edited by John Goodrich; Video edited by Liu Chen; and Room with a View produced by Tian Yi)

954km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3