Business

11:08, 17-Dec-2017

Taxing task: China's deleveraging push

CGTN

The ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes once said, "Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world." But make the lever too long, and it may break. The same is true for a country using leverage to take on public debt.

Rapidly growing levels of leverage in China have triggered mounting concerns, and prompted the top leadership to intensify its efforts to contain risks and brand deleveraging its top priority in 2018.

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

The central government pledged to "prevent and resolve major risks to effectively control macroeconomic leverage ratios", according to a statement released after a meeting of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee earlier this month.

The meeting of senior leadership was a prelude to the upcoming Central Economic Work Conference where China's top leaders are due to map out an economic and reform agenda for 2018.

The conference will be held from Monday to Wednesday.

What is debt-to-GDP ratio?

The debt-to-GDP ratio is the ratio of a country's public debt to its gross domestic product. By comparing what a country owes to what it produces, the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates the country's ability to pay back its debt.

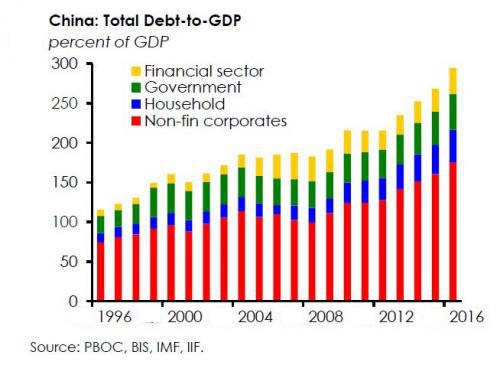

China’s total debt-to-GDP ratio had surged from around 180 percent in 2011 to 247 percent in 2016, data by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) showed. The figure has shrunk to 239 percent in the third quarter of this year.

The total debt is the combined debt for (non-financial) corporations, governments and households. The corporate sector, in particular state-owned enterprises (SOEs), accounts for a large proportion of the total debt that China holds.

Corporate debt-to-GDP ratio amounted to 165 percent at the end of 2016, higher than the internationally accepted risk level.

China's big leverage crackdown

The country’s policy makers have long recognized the problem in the debt-ridden corporate sector and embarked on a series of measures, like debt-for-equity swap programs, elimination of zombie companies, overcapacity cut, and hard budget constraints on SOEs, to contain the rise of risky credit.

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

China released guidelines to encourage debt-for-equity swaps last year. As of September 2017, a total of 77 companies in China had conducted swaps worth more than 1.3 trillion yuan (197 billion US dollars), according to Reuters.

Consequently, corporate leverage dropped to 154.8 percent in the third quarter of this year, according to China's Quarterly Deleveraging Report published by the National Institution for Finance & Development (NIFD) in late November.

Furthermore, the country's leverage structure has shifted from the corporate sector to government and household sectors in 2017.

Government leverage rose from 37.7 percent in the first quarter of 2017 to 38.1 percent in the third.

While the central government debt still has room to scale up, runaway growth of local government debt is widely seen as a huge risk for China’s economy and financial system.

Over the past years, local governments have rapidly built up debt upgrading infrastructure through shadow banking. To curb the ballooning off-budget borrowing, Beijing has made efforts to impose fiscal discipline on localities, such as whittling down on local government bond issuance.

Household debt, though relatively small, is inching up, from 46.1 percent in the first quarter to 48.6 percent in the third. The Chinese government has imposed restrictions on property sales in a number of major cities to prevent speculative activities.

China’s efforts to curb financial risks

Governor of the People's Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan attends a news conference at the Great Hall of the People, October 19, 2017, Beijing, China. /VCG Photo

Governor of the People's Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan attends a news conference at the Great Hall of the People, October 19, 2017, Beijing, China. /VCG Photo

China’s financial system is becoming increasingly vulnerable due to high leverage and accumulating "hidden, complex, sudden, contagious and hazardous" latent risks, said PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan.

Such concerns have led to sweeping new regulations in the financial sector as authorities sought to defuse financial risks without imperiling the economy.

On December 1, a top-level Chinese government body issued an urgent notice to provincial governments, urging them to suspend regulatory approval for new internet micro-lenders.

On November 17, the central bank and top regulators for banking, insurance, securities and foreign exchange jointly announced new asset management rules, aiming at reducing leverage levels, closing regulatory loopholes and reining in shadow banking.

In the meantime, China has been working to keep its currency stable by curtailing capital outflow, and September’s crackdown on crypto-currencies was the latest move to close an exit route.

"Broadly, China is making progress in controlling its debt in various parts of the economy," Christopher Lee, managing director in the corporate ratings group and chief ratings officer for Greater China at S&P Global Ratings, told CNBC.

"There is no one-size-fits-all way to deleverage and the government is utilizing a combination of incentives, deterrents and regulatory changes to facilitate an economy-wide deleveraging process," he said.

1km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3