Opinions

20:45, 20-Mar-2018

Opinion: China’s foreign aid re-haul is finally here – or is it?

Guest commentary by Hannah Ryder

The UAE has one, Korea's got one, India too. The UK has one and even Thailand has one. Last week, amongst the major changes to China's constitution and a huge government restructuring, China finally joined these countries with the announcement of a new specialized agency for Chinese foreign aid and international development cooperation.

Does the agency matter, and what will change?

Few questions were openly raised by the recipients of China’s aid across Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. Yet, of course, they – as partners or recipients – matter most in this equation. Indeed, for decades, China has advocated a “win-win” approach to cooperation with poorer countries.

What do China’s aid recipients want? The simple answer is MORE AID and MORE CONTROL (or, in development speak, OWNERSHIP). Regardless of the source of the aid, recipients want to deliver the most benefit for their people.

Currently, most poor countries feel that there is not enough aid from OECD countries, especially for new challenges such as climate change. Also, based on a range of metrics, less and less is directly benefiting the poorest. With many OECD countries merging their aid ministries into foreign policy and trade ministries, recipient countries fear they will get less and less aid, of poorer quality in meeting their needs.

In this context, there is a great opportunity for China’s new agency to make a mark and provide more and higher quality “country-owned” aid. But is this likely? The answer depends on the outcomes of four more detailed issues.

An aid increase?

First, in 2015, the Chinese government already made a series of announcements in relation to aid increases, including the now operational “South-South aid fund” and the yet-to-be-disbursed 3.1-billion-dollar worth of international climate change fund, which the newly formed Ministry of Ecological Environment is likely to be responsible for. There is no indication of further increases in Chinese aid, especially as it will take time for the new agency to form under its new vice minister, and physically bring together teams that formerly sat in China's Ministry of Commerce and its Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

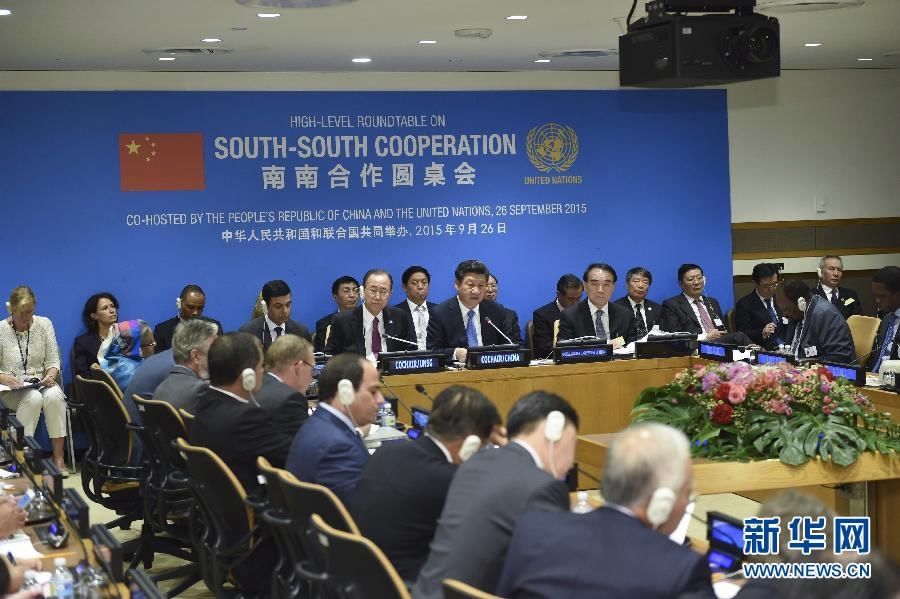

Sept. 26, 2015: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the High Level Roundtable on South-South Cooperation, New York, US. /Xinhua Photo

Sept. 26, 2015: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the High Level Roundtable on South-South Cooperation, New York, US. /Xinhua Photo

More country-specific support?

Second, while the agency will be in charge of overall “country plans” for aid recipients, ensuring the plans are more in line with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): These plans will not extend to commercial loans, nor is it guaranteed that other aid spending government ministries will use them. There is also no suggestion that these plans will be published or shared with recipient governments for their comment.

This means that internal coordination to enhance what China can offer through the BRI will increase, especially as the agency will now be directly answerable to the State Council. But there will likely remain gaps in understanding of recipient country’s sustainable development goals and other key areas that only recipient countries themselves can identify. Risks may also remain, for example, in being able to assess how concessional loans and the BRI affects individual country’s debt sustainability. There is no evidence that loans from China are on their own creating debt crises, but this is nevertheless important for Chinese officials to take into account in the future.

Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (C) and Army Chief Raheel Sharif (2R) offer prayers at the opening ceremony of a pilot trade project between China and Pakistan in Gwadar port, November 13, 2016. /VCG Photo

Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (C) and Army Chief Raheel Sharif (2R) offer prayers at the opening ceremony of a pilot trade project between China and Pakistan in Gwadar port, November 13, 2016. /VCG Photo

More accounting?

Third, the official notice stated that the new agency will have accountability for implementation of China's aid. But will it be able to effectively count it? The last time the Chinese government published data about its aid was almost four years ago, and the value was put at around 4.8 billion US dollars per year. However, in addition to the other aid spending ministries, smaller quasi-government bodies who administer foreign aid money are likely to continue to do so, at least in the short-medium term. This will mean counting up China’s aid projects and breaking the figures down country-by-country will remain challenging. Such figures, however, are badly needed by recipient countries to be able to plan their engagement with China.

When I led UNDP's work on China's global cooperation, I commissioned my team to write a report on how 11 countries had managed to gather complete information about China’s aid in their countries. Six more countries have published such data more recently. But unless the new agency takes the initiative to share country-by-country information on aid flows, recipient countries will continue to have to shoulder this burden.

More quality standards?

Fourth, with more staff, the new agency will likely be able to provide as well as enforce more guidance to ensure other ministries and aid administrators improve the quality of the aid and make it more country-owned. For example, the agency could, like the UAE and Sweden do, ensure all aid procurement notices are openly published on its own website so that capable firms from poorer recipient countries could bid for them. Such firms exist and need support!

The agency could also ensure such notices consistently include minimum standards regularly demanded by poor countries, for instance green/energy-efficient equipment, or local employment/content requirements for new infrastructure. Recipient countries currently have no means of securing such demands, yet they are crucial to ownership.

Solar panels at a solar carport at the Garden City shopping mall in Nairobi, Oct. 26, 2016. /VCG Photo

Solar panels at a solar carport at the Garden City shopping mall in Nairobi, Oct. 26, 2016. /VCG Photo

The announcement of a new Chinese international development agency has been long predicted by many Chinese think tanks and NGOs. With it, China will join many other aid and South-South cooperation providers, improving its image and internal coordination as the BRI gathers momentum. But for it to make a difference on the ground, it needs to show recipient countries that it will be different from anything that has gone before. If the new agency can do that, I am confident China and its development partners will achieve “win-win” results.

(Hannah Wanjie Ryder is the CEO of Development Reimagined, an international development consultancy firm, and the first Kenyan wholly foreign-owned enterprise in China. The article reflects the author's opinion, but not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3