Culture

18:07, 31-Mar-2018

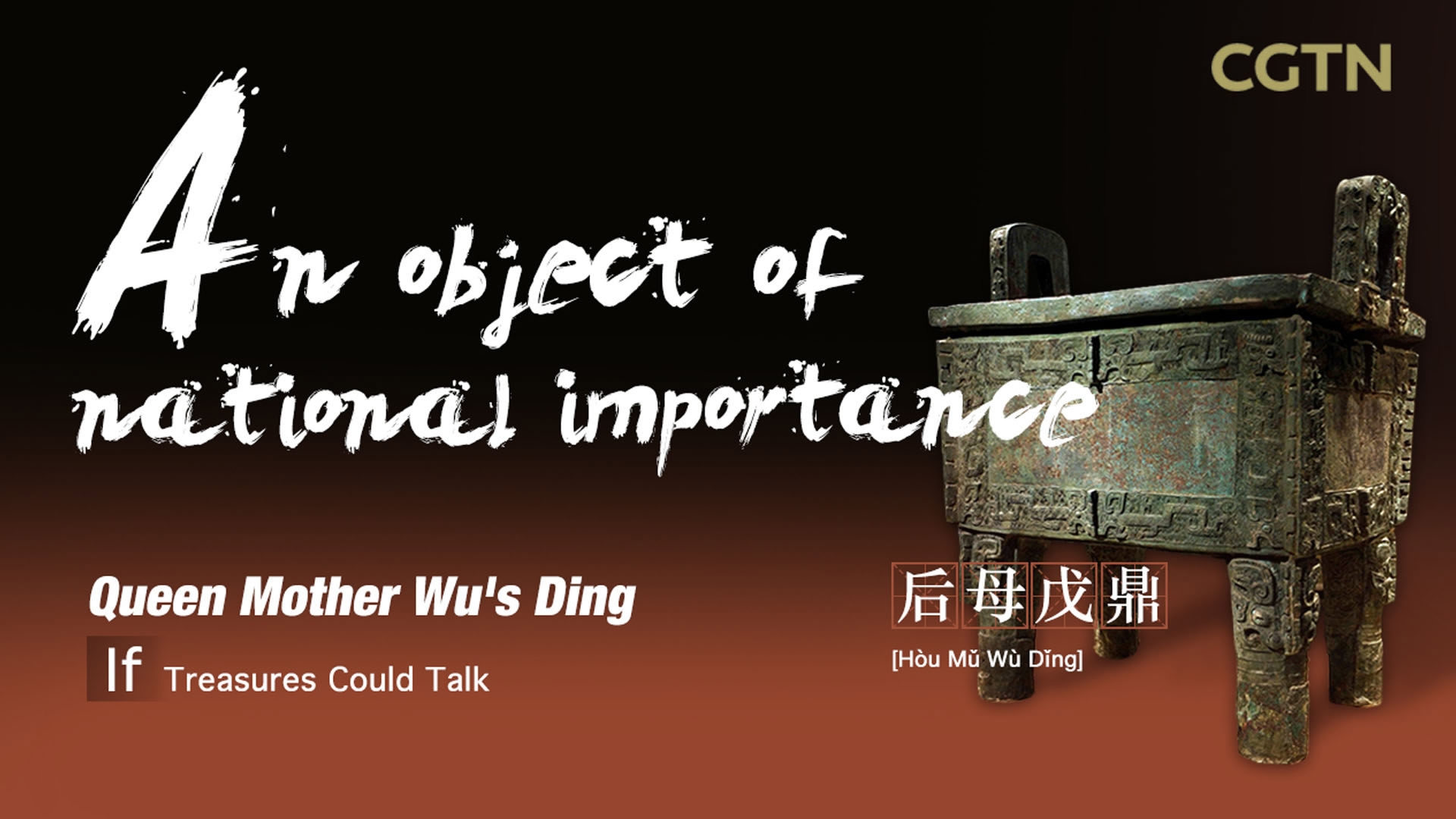

If Treasures Could Talk: What secrets would the Queen Mother Wu's ancient cauldron reveal?

CGTN

The series "If Treasures Could Talk" was a TV hit across China, inspiring many young viewers to learn more about their country's past. Today, we present to you an artifact that belonged to Queen Mother Wu.

Dings were large cauldrons that were symbols of power in ancient China. The one belonging to Queen Mother Wu is particularly impressive. The bronze ritual vessel dates from the height of the Shang Dynasty, nearly four thousand years ago.

From mining and smelting the ore, transporting it, and creating the alloy, to the casting, decoration and final molding, making it must have been a long and arduous process.

Queen Mother Wu's Ding on display in the National Museum of China on July 12, 2012. /VCG Photo

Queen Mother Wu's Ding on display in the National Museum of China on July 12, 2012. /VCG Photo

This huge bronze vessel weighs over 830 kilograms.

Creating it would have required a large team of experienced craftsmen, more than a ton of metal, and an enormous furnace. Various experts who have analyzed the marks left by the mold have arrived at a number of theories as to how the ding was made.

Some believe it was cast in parts. Others say the body was created in a mold, with only the handles added later. If this were the case, careful control over the cooling process would have been needed, as the different parts vary in thickness. We can only speculate over how many attempts were made before success was achieved.

An inscription on its interior identifies the ding as being dedicated to Houmuwu – Queen Mother Wu.

Queen Mother Wu's Ding on display in National Museum of China on November 29, 2011. /VCG Photo

Queen Mother Wu's Ding on display in National Museum of China on November 29, 2011. /VCG Photo

Most experts believe that Houmuwu refers to King Wu Ding's queen, Fu Jing. They point to the fact that the grave of another of his wives, Fu Hao, contains a very similar ding, inscribed with “Queen Mother Xing.”

To the ancient Chinese, the earth was square and heaven was round. The earth was also female, and the mother of all things. This leads us to the conclusion that square dings may have been used by high-ranking female priests in offering sacrifices to the earth.

A ding, planted firmly on its four legs, was synonymous with stability.

With time, dings became symbols of state power. Still today, the character for “ding” appears in many Chinese words describing something that is solemn and dignified.

The biggest of them all, Queen Mother Wu’s ding, has become an object of national importance, exuding an aura of ancient power and glory.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3