Health

21:47, 21-Mar-2018

'Two Sessions' focus: Ethnic minority medics hope for better rural healthcare

By Tao Yuan

Past healthcare reforms in China included the expansion of medical insurance coverage into the country’s rural backwaters, making sure rural communities have access to basic healthcare. But such policies have done little to ease some of the most pressing problems in China’s medical system.

“We have all the equipment,” says He Yongqiao, a neurologist from Garze, an ethnic Tibetan county in southwest China’s Sichuan Province. “But our medical staff is not well-trained enough to handle some of our patients.”

He holds an undergraduate degree in neuroscience. Most of her predecessors at her hospital trained at secondary vocational schools. “Many of our patients don’t have basic trust in us, and with good reasons,” she said.

For China’s rural residents, hospitals in big cities are often better equipped to handle more serious conditions. This means city hospitals are often overcrowded with patients. On average, China’s largest hospitals can receive close to 20,000 outpatients per day.

Hospitals in China’s big cities are often overcrowded with patients. /CGTN Photo

Hospitals in China’s big cities are often overcrowded with patients. /CGTN Photo

“For many patients, a lot of precious time is wasted on traveling to city hospitals,” says He. “In some remote places, that takes hours or even days, and that time could well mean life and death for these patients.”

He is now an exchange fellow at West China Hospital in Chengdu city, one of the most prestigious hospitals in Sichuan Province and the whole country by large. She will get training here for a year, and bring what she learns back to her hometown in Garze.

Such program is part of a countrywide drive to overhaul China’s rural healthcare system. Officials call this a regional medical alliance – connecting top-tier hospitals with local-level hospitals in training partnerships to ensure better medical practice at every level.

The president of West China Hospital, Li Weimin, is a deputy to the National People’s Congress, China’s top law-making body. At this year’s “Two Sessions,” he called for strengthening the medical alliance, especially in ethnic minority regions.

Li also wants to set up long-term incentives for doctors to work in ethnic minority regions. Promotions, for instance, will be based on their record of serving in hospitals in those regions.

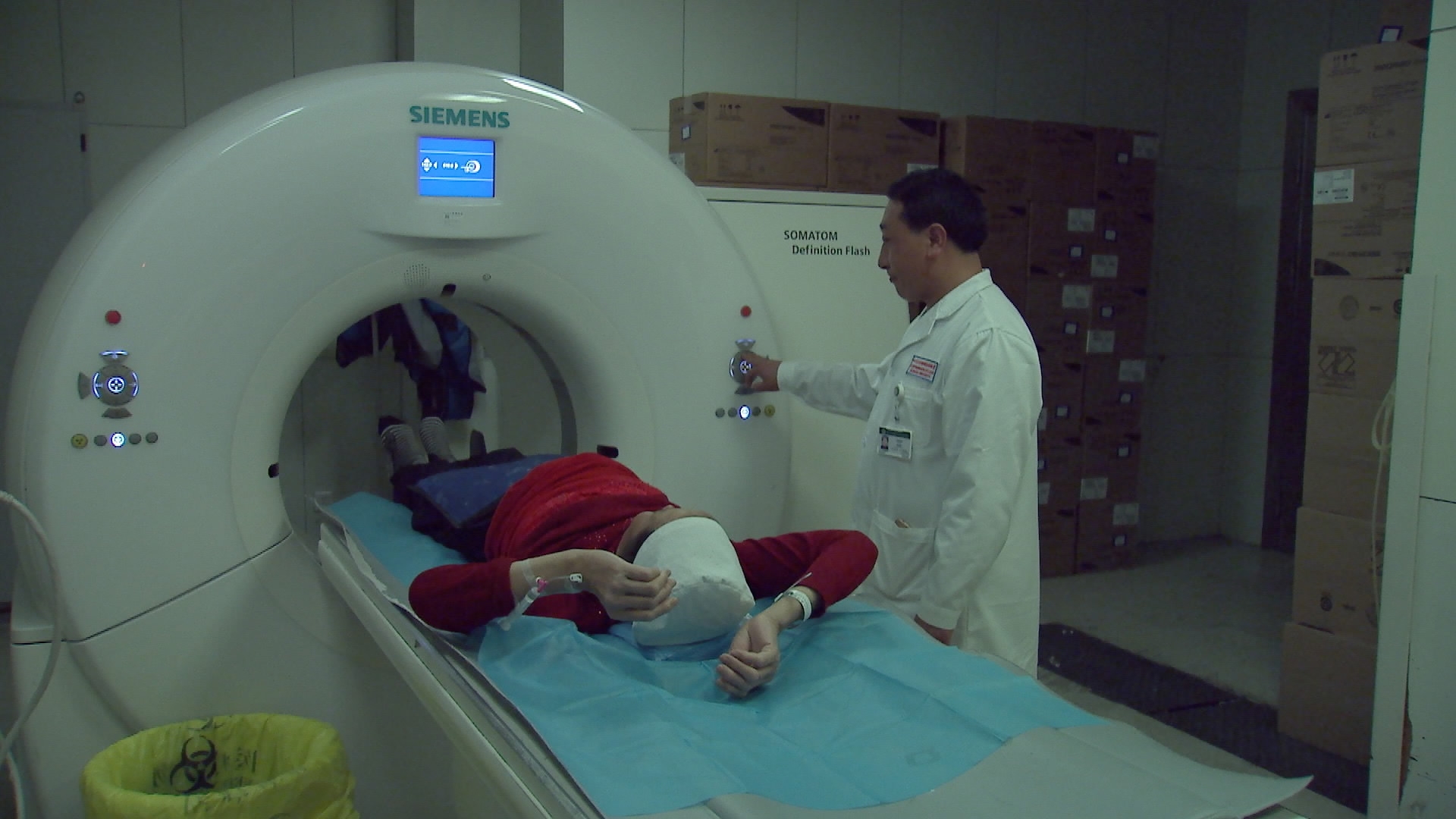

Wazha is another fellow at West China Hospital. He’s a radiologist from an ethnic Yi county, one of the poorest regions in China.

Wazha, a Yi ethnic minority radiologist, is studying at West China Hospital under a regional medical alliance. /CGTN Photo

Wazha, a Yi ethnic minority radiologist, is studying at West China Hospital under a regional medical alliance. /CGTN Photo

“Many of my patients even don’t speak Mandarin,” he said. "When we can’t treat them at the county hospital, some of them give up and go home. It makes me so sad.”

Yang and Wazha are among the first local doctors to start making a difference. More people will likely join their ranks, narrowing China’s urban-rural healthcare gap.

1522km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3