Culture

13:29, 06-Nov-2017

'Senior drifters' find big city life a lonely challenge

CGTN

Many migrant senior "drifters" are battling loneliness and depression in China's biggest cities, as Wang Keju reports.

A growing number of senior citizens are moving to China's larger cities to be with their married children and help look after the grandchildren, but rather than finding a source of solace, many end up feeling lost, abandoned and isolated.

Senior "migrants" living in cities like Beijing and Shanghai can easily be spotted in their residential communities, at school gates or in supermarkets.

They left their hometowns to live with their grown-up children far from friends and familiar surroundings. Instead, in many cases, they simply have become childminders for the family's third generation.

Many seniors who have moved to large cities to live with their adult children say they are losing touch with old friends at home and being treated as unpaid babysitters or housekeepers. /Xinhua Photo

Many seniors who have moved to large cities to live with their adult children say they are losing touch with old friends at home and being treated as unpaid babysitters or housekeepers. /Xinhua Photo

Floating population

According to The Development of the Migrant Population, a report published by the National Health and Family Planning Commission last year, people aged 60 and older account for 7.2 percent of China's floating population of 247 million. That's about 18 million people, roughly twice the population of New York, and about 68 percent of these elderly migrants relocated voluntarily to live with their children or care for the grandchildren.

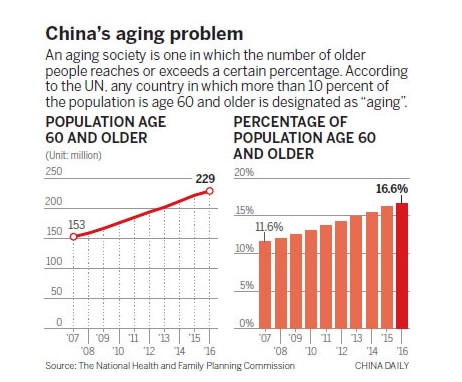

China has now more than 200 million people age 60 and older, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

The dilemma faced by elderly migrants becomes more stark as their little grandchildren began kindergarten.

Now suddenly without company, they have no way of killing time and have become known as senior drifters.

"The phenomenon of 'senior drifters' is closely related to the ever-growing number of migrants and ongoing urbanization," said Zhou Xiaozheng, a sociology professor at Renmin University of China in Beijing. "Just as young migrants struggle to get by in cities, seniors who move to the metropolises will encounter even more trouble."

With few friends to chat with, let alone to sing Huangmei Opera, many senior citizens become swamped by memories of the old days back home, combined with loneliness and depression.

"People back in Huaining envy me for living in Beijing but I'm jealous that they can stay at home with old friends and relatives," 61-year-old Chen Lizhen said.

China's aging problem at a glance. /China Daily Photo

China's aging problem at a glance. /China Daily Photo

Walking a tightrope

Moreover, caring for her grandson full-time was like walking a tightrope every day. "I could not allow accidents to happen to him. My life was basically centered on him," Chen said, adding that cooking, feeding the baby, playing with him and lulling him to sleep left her little time for herself.

Jiang Xiangqun, deputy director of the Gerontics Research Center at Renmin University, said senior citizens have a strong attachment to their native places and long-term relationships.

"Being cut off from their familiar environment leads to a range of psychological problems, which many sons and daughters neglect," he said.

According to the Statistical Science Research Center of the National Bureau of Statistics in August, a lack of social activity results in about 25 percent of seniors feeling isolated, anxious and depressed.

Five years ago, Zhang Shuqin, left her home in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang and moved to Beijing to live with her daughter.

Unlike many of her senior drifter peers, Zhang came to the capital following retirement and believing that the end of her working life signaled a new beginning. However, it took time and effort to fit in.

To avoid feeling like a non-local resident and not blending in, the then 50-year-old began reading about the capital's customs and history, and visiting famous tourist spots.

Now, she talks about Beijing as though she has lived in the city for decades. "Even my neighbor, who is a real Beijinger, calls me a half-Beijinger," she said.

Despite her greater familiarity with the capital city, Zhang still encounters obstacles every day, such as a lack of medical insurance.

The issue is not just a pressing problem at her age, but also a constant reminder of the gulf between herself and native Beijingers.

To claim reimbursement of medical costs, senior drifters like Zhang have to travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometers to their hometowns and go through complicated procedures.

The reason is that the system is based on a person's hukou, or household registration, which means that medical costs incurred away from home can only be reimbursed in the place where a patient's hukou is registered, usually their hometown.

In addition, medical treatment costs are higher in large cities, according to Zhang, who noted that the cost of treatment for a cold in Beijing is about 300 yuan (45 US dollars), but it costs less than 30 yuan in her hometown.

Although she can absorb costs of that nature, whenever she has had a more serious illness, Zhang has been forced to return to Heilongjiang to be reimbursed.

Every time she goes home, she returns to Beijing with many local products, and a large bag of medication.

"People on the subway looked at me as though I was an illegal 'medicine dealer'," she said.

After a couple of periods in the hospital, she is for the first time considering going home for good. "I'm at an age when illnesses get in line to find me. I cannot place such a heavy burden on my daughter," she said.

Migrant seniors tend to miss their old lives. /Photo via lishen.net.cn

Migrant seniors tend to miss their old lives. /Photo via lishen.net.cn

An unbearable burden

Chen Biao, professor of geriatric science at Capital Medical University in Beijing, said time is catching up with many senior drifters.

"People aged 65 to 69 are at the lowest level of health. Therefore, once their health insurance is exhausted, the cost of treatment becomes an unbearable burden for their families," he said.

The medical needs of senior drifters directly influence their sense of belonging, and the government has long been pushing for cross-provincial medical fee settlements to provide greater convenience and help.

Last month, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security confirmed that the groundwork has been completed to build an "expressway" for the direct settlement of cross-provincial hospital expenses. That will allow senior drifters to apply for reimbursement of medical expenses without going home.

Confronted with these physical and psychological problems, many senior drifters are still wandering around large cities in desperation.

Chen was not happy when she was told that her son and his wife have been discussing having a second baby.

"I miss my old pals. I really hope I can go back and sing Huangmei Opera with them," she said.

Source(s): China Daily

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3